jol·ly

noun

Prob. from jolly boat but perhaps also connected with the army sense of jolly; a thrill of enjoyment or excitement [recorded in NOED from 1905 onwards].

An excursion away from base, either for recreation or work. 1992 45th ANARE Casey yearbook 1992 [Casey ANARE, Antarctica]:56. [glossary]

A jaunt away from the station into the wilderness, including work ‘jollies'.

The Antarctic Dictionary, Hince, 2000; 196

Last month, I wrote about all the boring work stuff we never write home about, so to balance it out I thought I'd write about our times off station this time. Of course there are weekly stories on individual trips as it is, but I feel a more detailed approach is called for to give some context to the good old jolly.

Jollies, as the word conjures up, are all about having a bit of fun, a break in the normal routine and a few hours or nights away from the station. They come in all variety of forms: work jollies, mega jollies and a pure jolly. Jollies are serious business though, because if we couldn’t get off station for the year then quite frankly we’d all go stir crazy. No one would enjoy their time in Antarctica and consequently few people would ever return South, which would mean that the Australian Antarctic Division would lose the skills and knowledge of returned expeditioners.

What defines a jolly? Well pretty much any trip that entails leaving station is regarded as a jolly, even if you go out for work, get stuck in a blizzard and come home cold and miserable, it’s still a jolly as far as everyone back on station is concerned. A work jolly might be out to a hut to do some maintenance such as tighten some guy ropes, install a new oven (as is on the agenda this year), replace the food stocks and the list goes on. A pure jolly involves no work at all. In reality though, most jollies are a mixture of work and pleasure. People head out for a weekend away and if there’s some work to do then they do it while there. A couple of months ago, we replaced an oven at Rumdoodle Hut.

Some people like active jollies, where they get to the hut and then go walking in the hills for sometimes hours. Quite frankly though, this isn’t my cup of hot Tang (more on this later). When I go on a jolly, it’s to have a rest away from the noise of station and the buzz of my pager. I kick back, read, have a chat, and take a few (thousand) photos close to the hut.

Different groups have their own jolly styles. It’s generally understood that if you jolly (there is a considerable waiting list) with Vicki, Chris and I, then chocolate will make an appearance, albeit briefly once Vicki or I get our eyes on it. Fray Bentos steak & kidney pies will be on the menu one night and toasted cheese & bacon sanga’s (sandwiches) will be eaten for breaky every morning. In winter, our morning starts when the alarm goes at 9:45am warning of the impending sked at 10am.

As fun as these trips are and as warm as the huts can be after the heater has been on for a few hours, there is always a serious side to the very existence of our field huts. If things do go wrong or the weather turns for the worse while people are out in the field then the huts are literally life savers with their heaters and stoves, stocks of food and somewhere to have a snooze for a few hours or hunker down for a few days until a blizzard passes. As such, whenever leaving a hut it’s a matter of courtesy to leave a saucepan on the stove with water in it, ready to be heated up if needed should a party arrive with someone injured or hypothermic. Of course the water in the saucepan will be ice when a new party arrives but it’s still the easiest thing to melt for hot drinks. A saucepan with only snow to fill it will take ages to melt down enough water. Another given is that one of the first things done on arrival is to put the heater and kettle (saucepan) on. Everyone is always up for a warm drink on arrival, particularly if you've arrived on quads. It’s quite dehydrating down here so a warm drink never goes astray.

In 2009, after completing my basic field training I went on my first ever real jolly with Cath K, Lisa O’C and Matt L, locating and documenting tagged Weddell seals. This is where I was introduced to the true Antarctic experience of ‘Hot Tang'. Debate can rage for minutes over the virtues of orange versus lemon Tang, but in my book there’s no comparison. Orange is by far the best. Some people won’t touch the stuff though, preferring coffee or plain old tea. I still maintain though that to be a true Antarctic expeditioner you have to partake of some hot Tang on jollies. I never touch the stuff otherwise, as much as I love it, and I do, I don’t drink it back in Australia. It’s only for Antarctica.

Jollies take some organising too. It’s not just a case of grabbing a jacket and heading off. Forms need to be filled in with your intended trip location and travel route, the hut booking board has to be filled in, vehicles sorted with all the correct rescue and survival gear packed, food, radios, GPS, spare batteries etc. and then there’s a weather window to wait for. It’s quite a task but once you do it all and leave station, it’s well worth it.

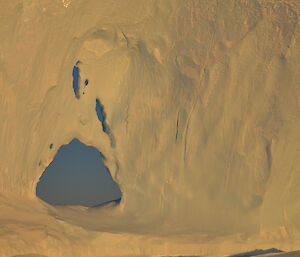

Jollies have their seasons. When we arrived here in February the sea ice was still closed, in fact it was still water, so all trips were up onto the ice plateau, where we have 3 huts: Mt Henderson, Rumdoodle and Fang Peak. With the sea ice now well and truly formed there was a science jolly to Colbeck in early July to count the adult emperor penguins in the Taylor Glacier colony, and closer to home there is the Auster emperor penguin colony with the closest hut being on Macey Island.

Just a few kilometres across the sea ice from station we have Bechervaise Island with some Smarties (Googies) for accommodation. These are lived in all summer by penguin biologists and we have the occasional jolly there in winter too.

However, at this time of year with the emperor penguin chicks hatching, if you hear someone’s heading out for a jolly, it’s a safe bet it’s to Macey and Auster-the penguins are a sight to see indeed.

P.