Our project aims to better understand the interaction between solid Earth and the ice sheet of East Antarctica. We want to know how changes in the ice mass can affect global sea level, but to achieve that, we need to collect more data. One of the more challenging locations for our data acquisition is a tiny rocky outcrop (nunatak), in Princess Elizabeth Land. Last year, the nunatak was named after one of Australia’s most famous geologists, professor Samuel Warren Carey.

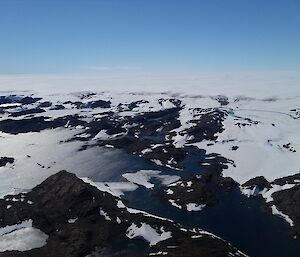

The helicopter flight from Davis station to Carey Nunatak is indeed very beautiful with the white ice to the south, the blue ocean in the north. The view caused some problems when we tried to make time go a bit faster by playing ‘I spy with my little eye’ with the other helicopter over radio. We came up with ‘horizon’, ‘Ingrid Christiansen Land’, ‘Antarctic Circumpolar Current’, ‘chord’ (referring to a tiny chord in front of the windscreen), but then there wasn’t really much else to refer to. Snow, sun, sea or sky would have been too obvious and ‘cows’ wouldn’t have been all that true. Sometimes you just have to except that it’s really big, monotonous and very far to go. To look down at the crevasses cutting through the ice under the drifting snow is a reminder that it’s also really dangerous land.

Geophysicists like myself go out with hammer drills, bolting GPS receivers to strategically located outcrops. This lets us measure how the continents are slowly but steadily sailing around the planet on an ocean of glutinous melted mantle, rebounding from the melting ice load, or submerging under the pressure of growing ice sheets or volcanoes. We also know that the continental plates are rather bad navigators. Sometimes they rock as earthquakes strike their hull, sometimes they change course, slide and scratch along each other, fall apart or deform. Sometimes they even sink, if the mantel keel gets too heavy.

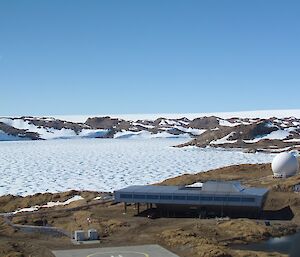

To be able to understand the history of the Earth, we need observations, and we can’t get the observations from UTAS’ Sandy Bay campus in Hobart and unfortunately not even from the panoramic windows in Nina’s Bar at Davis station. This is why the operations coordinator, meteorologists, radio operators, aviation ground support, pilots, mechanics, field guides, Marcello and myself, struggled the whole Sunday to get to Carey Nunatak with fuel drums, 320 kg of equipment and packages of salty biscuits that eventually ended up as crumbs in the backseat of the helicopter.

At Carey Nunatak we deployed a GPS receiver with a solar panel to provide reliable power for years. We also installed a seismometer to measure vibrations and noise from distant earthquakes and collected two backpacks full of rock samples.

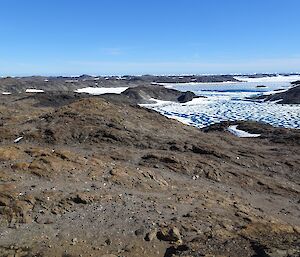

The main challenge for deep field work is the environmental protection. I think I saw at least six different kinds of lichens and mosses on the nunatak. Could any of these be endemic to the site? Any contamination from other outcrops could be harmful for these organisms. I washed my crowbar in ethanol and we tried our best to step carefully on the rocks not to harm these sensitive fellas. I get a strong connection to the inhabitants I meet at these remote locations. They were maybe there already when Ui-te-Rangiora or Captain Cook first approached the Antarctic continent. If I remove a rock and find a patch of lichens hiding from the wind and the UV-light, I’ll carefully put the rock back in place. Sorry to disturb, stay safe!

We are not the first people to visit the outcrop. Most sites we went to during the field season have been visited previously by Soviet and Russian scientists. We found triangulation markers, notes in cairns and Antarctic heritage rubbish. Hopefully our work will add important knowledge to the accumulated international understanding of the Antarctica. It’s of global concern.

Flying home with hours still to go, Toby (the pilot) interrupted the small talk in the chopper and asked with an unusual sincerity; ‘Why do we need to go so far to do your science?’

Funny, I was actually asking myself the same question. Because that lichen draped and weathered rock is our only peek into the crust for hundreds of kilometres. It’s our first glimpse into a secret land, hiding under a veil of ice.

The season is approaching the end. It has been a great time, both at Casey and Davis, and it will be sad to leave Antarctica. Sorry to disturb, stay safe!

Toby