During a couple of field seasons we’ve been collecting data to understand how the ice sheet interacts with the solid Earth beneath and how this interaction can help us to predict global sea level changes.

It’s not easy, as the rocks we are interested in are usually hidden under kilometres of ice, but we have a broad range of techniques to indirectly measure what is going on. This interdisciplinary approach is sometimes challenging but needed and rewarding.

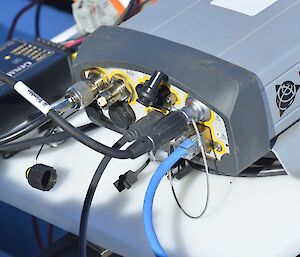

When ice is melting, the Earth responds with an uplift, just as the mattress regains its shape when you step out of bed in the morning. We have deployed precise GPS–receivers on outcrops along the coast to measure the few millimetres of response when the mass of ice is changing.

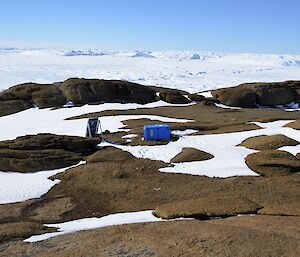

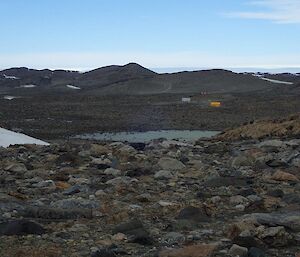

The GPS–antennas are bolted onto the bedrock and prepared to, hopefully, survive for years in some of the harshest environment on this planet; the summits of nunataks and islands in East Antarctica.

It’s a rather emotional moment to leave the instrument at an outcrop that will not be visited for years. People who check twice if the stove is off wouldn’t enjoy the stress of flying away from a distant outcrop and suddenly start to doubt if that last blue cable was really connected.

We also deploy seismometers to measure seismic waves from distant earthquakes. The signals are used to calculate thickness and character of the continental plates and even estimate temperatures at depth. The sensors are buried in the ground, protected from the noise of wind and are surprisingly sensitive. I find it rather relaxing to convert the seismic signal to sound and listen to it to relax in my spare time.

A lot of interesting vibrations occur during the long isolated winters. Most of it sounds like frying greasy bacon when sped up 200 times or so, but sometimes there is an infrasonic fart or burp resonating through the icy continent that causes the billion years old mountains to shake a bit, as a distant memory of when they themselves where young and dynamic and rocked the world.

Finally we also collect rock samples for analysis back in Hobart and Canberra. This is purely classic geological labour and it literary means that we swing the geology hammer and crack a piece of weathered charnockite or gneiss, tuck it in a canvas bag and carry it around in the backpack for a day or two. Mawson or Taylor would have done it exactly the same way. We’ve only replaced the sledges with choppers and the huskies with pilots.

We are interested in how the ice extent has changed in the past. From the rock samples we can detect how long the rocks have been exposed to the sky and therefore when the site was last covered by ice. We also use the samples to constrain the geological domains, how old and rigid the rocks are.

Most amazingly, some rocks can tell a number of stories at once; the story of how it was formed, maybe 2.2 billion years ago, how it was later part of a number of mighty mountain chains, how it was ripped off and transported by a glacier and finally how it’s now sadly weathering in the wind and eventually ends up in the ocean as mud and maybe digested by some dull sea–worm. If nothing else, it’s a beautiful reminder to check the pension saving scheme in time.

We have already got useful samples and data that will eventually keep us busy for a good while in offices and laboratories back in Australia. This year we have finished the work from Casey and are now spending the days in The Vestfold Hills; waiting for good weather to deploy the last instrument and collect the last backpack of rocks.

We are in a good mood and lack nothing.

Toby, for the King project