Hi everyone,

It’s that time of year when the sea ice is thick enough for us to travel on safely and the male emperor penguins are coming to the end of their epic 115 days of incubating the precious egg on their feet.

With this in mind, it’s also that time of year when Mawson expeditioners eagerly await a suitable weather window so we can pack all our kit, crack out our zoom lens cameras, and head out to the Auster emperor penguin colony, one of the main reasons many people choose to winter here at Mawson, the only Australia station where we can visit the emperors.

With our trusty Met Team keeping us up to speed on the weather front, everything was shaping up for our departure on Sunday the 8th of July. On the said morning, well fed from our delicious Saturday night dinner, our group of six congregated in the dining room at 8am, only to sit around drinking coffee while we wondered why we met so early. The two Hägglunds were fully packed and ready the day before and, with no intention of leaving station until 10am due to the lack of light, we could have slept in a little longer.

Final checks made and chocolate stocks checked it was all systems go for the first trip this season to Macey Hut, some 50km east of station, with the Auster colony approximately another 10kms.

Travel on sea ice is quite safe but you have to be constantly on the lookout, checking for signs of thin ice and tide cracks. With the ice thickness measuring greater than 800mm and increasing as the winter progresses the biggest potential obstacle are tide cracks. These form from islands and icebergs as the edges part with tidal movement. Thankfully we came across only two notable tide cracks, and both of these were less than 500mm wide and had refrozen, so were safe for the Hägglunds to cross. Being the first trip out, it was our job to follow the set way pointed route from last year, ascertaining if the route was still safe to use and that no icebergs had floated in last summer and blocked the way. In good weather there is little to worry about and one might get complacent and wonder why routes are so important, but if the weather turns and you’re stuck out in poor light, poor visibility or poor ground definition then the GPS way pointed route suddenly pays its way, and in the unlikely event of getting caught in a white out, it’s a godsend.

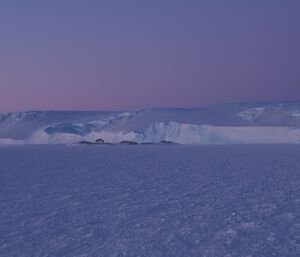

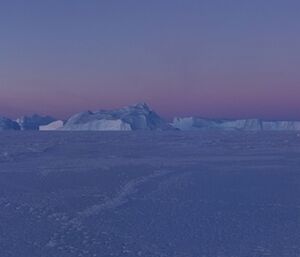

We had perfect weather all the way and quite a good track which made for an enjoyable three hour drive out with the plateau and ice cliffs following us to our right (south) and icebergs dotted along the way. Some of the icebergs were mighty big: quite something to see. I never tire of sea ice travel and looking at icebergs.

On arrival at Macey Hut, we dug out the door to the hut, parked the Hägglunds up and refuelled them ready to head out early tomorrow to find the penguins. Being the first trip out since last summer, we checked that all the gear was in working order, looked over the hut for any damage from winter winds, and settled ourselves in for the evening, which for me as always involves a delicious cup of hot orange Tang, the true Antarctic experience indeed.

Pete