It is mandatory that all winter expeditioners undertake three days of survival training in the field to give us the skills needed to operate away from station and during extreme weather. Our field training started off with a registration process to detail what our plans were.

This was followed by collecting our field packs which contain a sleeping bag, bivy bag, ice axe, maps, compass, boot chains and more. In addition, we add a few spare layers of clothing and survival food. We then visited the doctor who showed us through a medical kit before collecting our own for the trip. Then it was off to comms (communications) to collect a handheld GPS device, personal locator beacon and radio. After all this it was time to set off! Our team consisted of Marty (field training officer), Goldie, Jen and myself (Aaron).

We left around midday for the hike to Brookes hut, a distance of approximately 11 kilometres. With the temperature hovering around −5.6°C we started walking along the rocky Dingle Road and, dodging slightly frozen puddles of water, we made our way to the turn off point to follow the lakes.

From here we were walking over terrain strewn with large rocks resembling the landscape of Mars. We first came across Lake Dingle and then Lake Stinear, approximately three kilometres long, walking along the water’s edge below rock and ice cliffs. By this time we’d been walking for about four hours and still had a fair way to go until our destination. Using the compass and maps to guide the way, and the GPS as a confirmation that we’d figured it out right. We reached the end of Lake Stinear and felt like such an achievement to get to that point. Across another hill and we were greeted with the magnificent Deep Lake. It is located at 51 metres below sea level, the lowest accessible point in Antarctica! The salinity is ten times saltier than the sea. Not the nicest water to taste!

After a short stop we continued on our way using map and compass, over a massive hill of rocks and onto a steep sheet of ice. Having to get out our spiked boot chains, we navigated our way up and over. With only 1.3 kilometres to go, the end was in sight. Eventually after one more hill we could see Brookes hut overlooking the slightly frozen sea of Shirokaya Bay.

After six and a half hours walking, it was such a relief and a sense of achievement to have reached our destination. Brookes hut was originally constructed in 1972 and since then has been a refuge for expeditions on long traverses around the area providing four beds and a basic kitchen.

As part of our survival training, our dinner consisted of a dehydrated meal. I had chosen beef teriyaki which sounded great, looked less than desirable but did actually taste very nice — just add boiling water and wait 15 minutes. Not that we waited that long as we’d worked up a huge appetite.

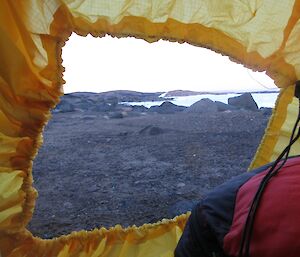

Shortly after, we got ready to sleep outside in our bivy bags. It was cold at first, but once you were in your sleeping bag it was really cosy. As soon as we had got into our bivy bags we heard a noise, halfway between a huge bang like someone had shot a gun and a cracking noise. It was the sound of the frozen sea ice moving with the tide. The fast ice is placed under tremendous pressure with the rise and fall of the tide. The sound and sight of it was just beautiful. It took me about an hour to get to sleep. I probably shouldn’t have set up next to two large rocks, one was enough.

Sometime in the early morning, I woke up to slivers of ice falling from the inside of the bivy bag right onto my face. This normally happens with warm breath meeting cold bivy, a significant difference in temperature. Apparently I should have left my bivy bag open more to breathe in the wind. After packing up we radioed into station and they told us the temperature overnight had fallen to −9.7°C. The lowest temperature for February that we've had.

We waited for the Helicopter to pick us up to take us to Woop Woop. Yes that is a name of a place where our ski landing area is on the plateau. As we left Brookes hut, the pilot gave us a nice view of the area that we had walked though. Amazing and so different from the sky.

Arriving at Woop Woop, we boarded a Hägglunds to do our training. At first, we followed way-points on the GPS while looking out the window, then once we were confident with the windows blacked out, only used the GPS to guide us. Very weird driving basically blindfolded but very realistic, similar to what is experienced in white-out conditions. White-out conditions are where you are unable to determine the horizon and there is no surface definition.

On returning from Woop Woop that evening we were treated to a magnificent meal prepared by the chefs. Food had never tasted so good before!

The next day our quad bike training was postponed due to high winds of around 30 knots gusting to around 40 knots. (55 kms/hr gusting to 74 kms/hr). We would have to wait for the next adventure.