At over 5,000 km from the Australian mainland and over 600 km from our nearest Antarctic neighbours, Mawson is easily the most remote of the Australian Antarctic stations. There are a few things, however, that make Mawson such a fantastic location and well worth the weeks of sea travel. Year-round, we have easy access to the ice plateau and the Framnes Mountains to our south. Adélie penguins, snow petrels, and Weddell seals keep us company in summer. But almost without argument, the stand-out experience of our time as wintering expeditioners here is the ability to visit local Emperor penguin colonies once the sea ice has locked in and thickened enough to support our Hägglund vehicles.

This year, we have been frustrated by the presence of a large polynya close to station (a polynya is an open area of water that is surrounded by sea ice), and together with a slow start to the ice formation with higher than average temperatures, it has only been in the last few weeks of minus 30°C days that we have seen the ice solidify enough to give us the confidence to head out from station. Last week we were finally able to conduct a proving trip 45 km to our east across the ice; we can now take day (or overnight if we are willing to brave the cold wintery conditions sleeping in a hut) trips to the Auster Emperor Penguin Colony.

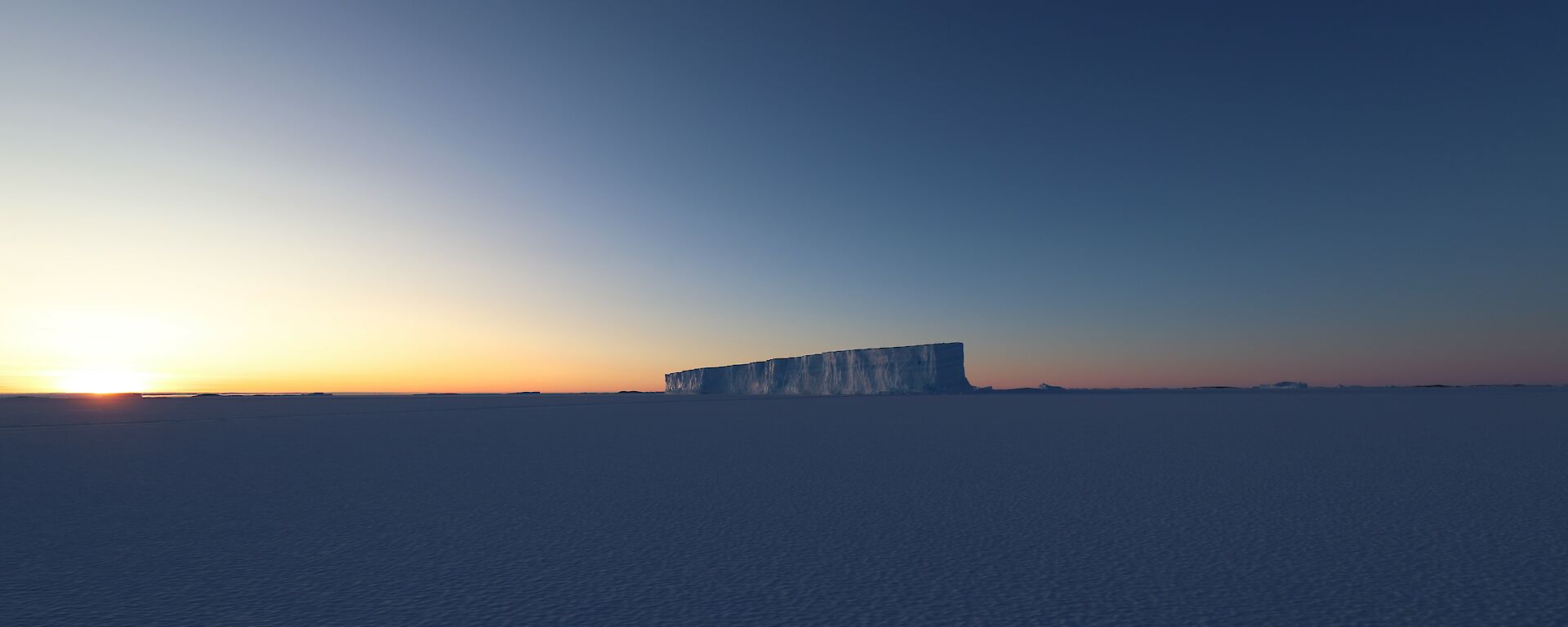

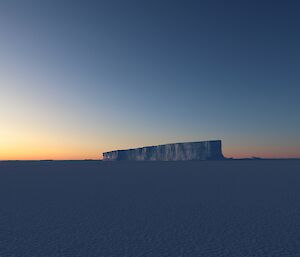

Two groups of expeditioners have already managed to take such an opportunity this week - despite the sudden appearance of a blizzard marking the first day of August. Becoming much more adept at preparing the Hägglunds the day before with all of our safety and personal equipment (not to mention quite a significant amount of camera gear!), we can also take advantage of the rapidly returning daylight to leave station at an almost ‘early’ 9 in the morning just as the sun is starting to light our way. The two-and-a-half-hour drive across the ice allows us the time to marvel at the sea ice, the trapped icebergs, the ice cliffs, and the ice plateau in the distance. Now that might sound like a lot of ice – and it is – and you may presume it all looks the same – it doesn't! The colours that play across the landscape, particularly during sunrise and sunset, are nothing short of spectacular. And given that our vehicles are not exactly the quietest of environments inside, the lack of chatter amongst us (imagine trying to have a conversation in a nightclub that only plays the sound of diesel engines as music) gives us the perfect excuse to just stare at the landscape surrounding us.

We park over 500 metres away from the colony to ensure that we do not disturb the birds. Particularly at this time in the breeding cycle when many eggs are still being cared for, and chicks are just starting to hatch. Any excess disturbance of the penguins can threaten the energy levels needed for raising the chicks and maintaining their body heat in the freezing cold wind. Nonetheless, the emperor penguins are naturally inquisitive and, having no fear of us, those that do not have young, immediately head over to us and our vehicles to investigate.

The next couple of hours pass in wonderment as we watch the colony and are approached by the birds. It is only when our extremities start to feel the cold even through our heavy protective jackets, boots, gloves, beanies, goggles, thermals … you get the picture … that we start to pack our cameras back up and head back to the warmth of our vehicles. The ride back to station is spent looking through our camera images, happily recalling the images that have already fixed themselves firmly into our minds.

Over the coming week, we will now also prepare vehicles and equipment for another attempt to travel nearly 100 km to our west to Taylor Glacier. This is the location of our next closest emperor penguin colony after Auster. Four weeks ago, our first attempt to reach Taylor was thwarted by the not-yet-thickened ice left by the polynya. With just over a month of additional freezing weather and good indications from satellite imagery, we are much more optimistic this time around!

Cat (Mawson Station Leader)