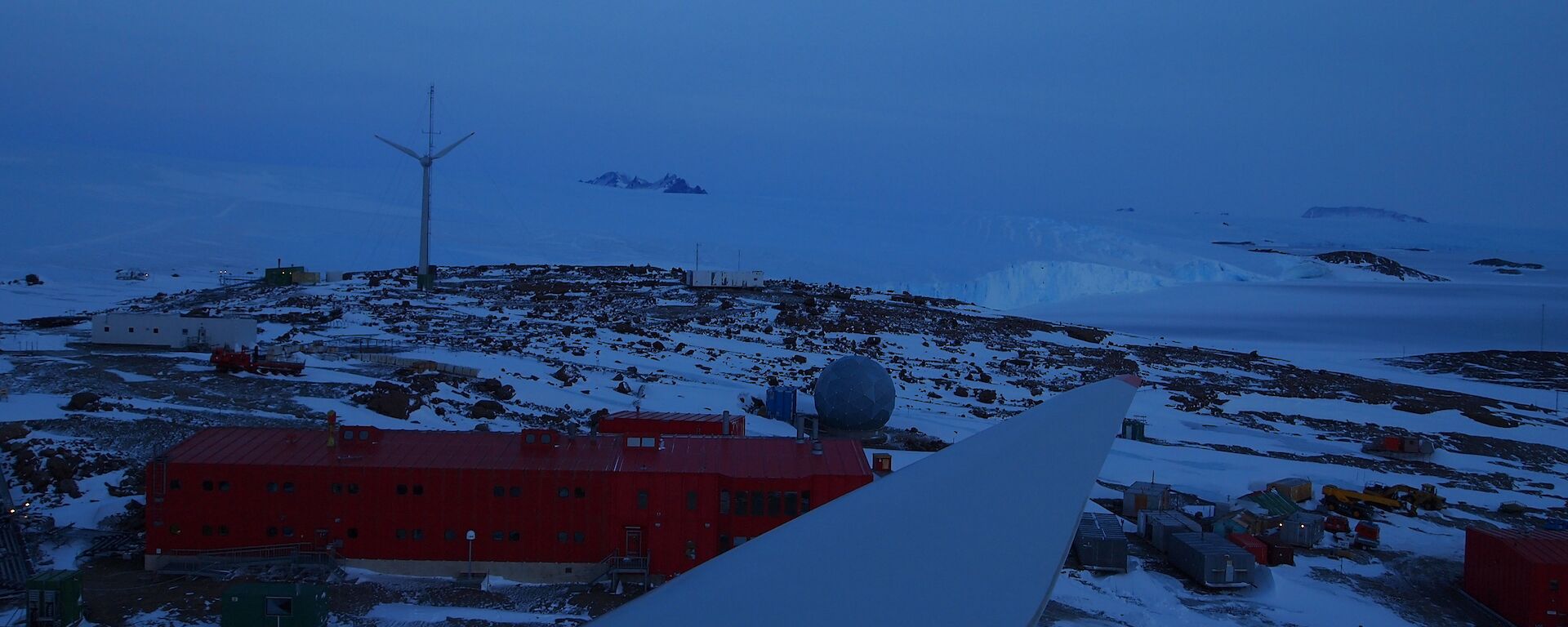

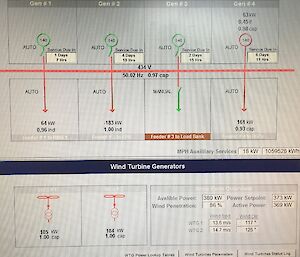

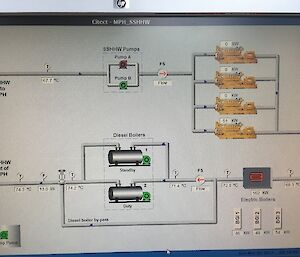

One of the things that separates Mawson from the other two Australian continental stations is the two wind turbines. With the hub of the turbine standing at around 30 metres high and a rotor diameter of 30 metres wide they’re not easy to miss. With the capability to produce three hundred kilowatts each, the turbines regularly produce more than 70% of the stations power with a fair chunk of that power used to heat the station via electric boilers.

The job of maintaining the turbines falls to the two electricians on station. This mostly involves looking at a computer screen but occasionally climbing the turbines is necessary. The turbine towers each have one ladder that goes all the way to the top and has a track down the middle which you attach onto with your safety harness.

When you do finally make it to the top of the tower, after catching your breath, you climb into the body of the turbine (nacelle). It’s a tight squeeze and at this point you’re thinking maybe that extra sausage roll at smoko was a bad idea.

When up there you start to cool down quite quickly and realise that the fibreglass shell isn’t the best of insulators, but if you’re lucky the turbine will still be warm which is very handy if your hands get too cold. The shell does do a good job of keeping out the wind so there’s no wind chill to worry about but at temperatures regularly below −20°C in the winter an extra layer of fleece is welcome underneath the overalls.

Most of the work up in the turbines is fairly routine like changing out the grease canisters and making sure everything is well lubricated, but occasionally there are bigger jobs like changing out the nose cone supports which after withstanding winds of 100 knots at times throughout the year can develop fractures from time to time.

But after the work is done, and if the wind is not bad, you can pop the top hatch and take a few photos from one of the best viewing platforms in Antarctica. Then it’s time to get back to the red shed and warm up.

Until next time,

Mark (Station Electrician)