The Christmas break at Mawson was expected to be a relaxing time with no major activities planned other than perhaps a walk or maybe some ice fishing on Horseshoe Harbour. After a big year it seemed timely to kick back and take it easy on the Boxing Day public holiday. By day’s end we had all received more excitement than could possibly have been planned.

The day started normally enough with people going about their business reading books, looking out the window at the view and no doubt catching up on some sleep after a busy year. A small group of enthusiasts decided to head out onto the ice in the harbour and try their hand at fishing. The ice around station is starting to decay as summer temperatures rise but was still useable and safe for travel. The sea ice is drilled and measured weekly as part of an ongoing program meaning we always have reliable and up to date information on its thickness. With a large drill, a few lines and some folding chairs these adventurers set out on what was intended to be a relaxing, uneventful afternoon.

The team back on station were settled in and generally relaxing when a radio call from the fishing team got our attention. There was something happening to the east of station making a lot of noise and causing a lot of snow and ice to be blown up into the air. The fishing team suggested we go and have a look while they made their way off the ice. Within minutes, the entire station were either at the windows or outside watching the most amazing display as Antarctica produced the most spectacular show that any of us had ever seen.

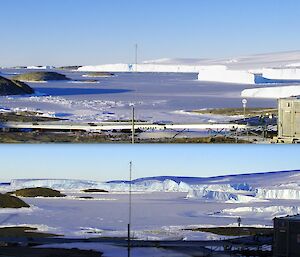

The noise and commotion the fishing team had heard (but could not see) was a large section of ice starting to break away from the coastline. The show had only just begun as the fishing team left the ice and the rest of us took up positions looking east as the ice began to separate. About two kilometres from station, a section of ice had decided it was time to go free. Numerous pieces of ice rolled and heaved, dislodging not only themselves but also pushing other pieces of ice further out to sea. Not only did the ice cliffs give way, but the surrounding sea ice was being smashed and broken as if it were eggshell.

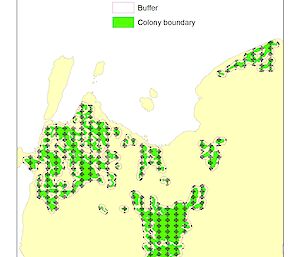

In the days following the event Corey (one of our team members) did some research and found satellite information showing the dislodged berg was around 1.3 kilometres in length! We had been watching from quite a distance away and struggled to get the true magnitude of what was happening, other than it was huge and very loud. We did some simple math and realised we had been watching millions of tonnes of ice being pushed around and broken up in a space of a few minutes.

The prompt departure of the fishing party from the sea ice was timely as the sea around station began to move back and forth causing a visible rolling motion in the ice. The movement of the sea caused torrents of water to gush out through cracks in the ice. As with everything down it here, it was incredible and just about impossible to photograph or capture in a video. After it was over, there was a sense of disbelief at how fortunate we had been to safely witness something that is so rarely seen.

Amazing!