After causing some readers (and editors) to get a little frazzled last week I thought I’d continue with my 101 sessions and this week concentrate, albeit briefly, on emergency response (ER).

So what happens when things do go wrong?

When managing an emergency the military, emergency services, governments, countless organisations and institutions and of course, the Australian Antarctic Division, all work from the same template. Whilst the world has been dealing with emergencies for a very long time it was at the end of the second world war that the world powers first united in their approach to emergency management and the first templates were developed. This template has grown and evolved ever since. And such is the dynamic world of emergency management that I can confidently say that it will continue to evolve as new technologies, equipment, tools and most importantly, our experiences evolve.

Just as we pass information and observations of sea ice behaviours and patterns from one expedition to the next, we do the same with emergency management. Basically my message here is we don’t make this stuff up as we go along. There are well researched methods that have been tried and tested and tried again that we, the Australian Antarctic Division, draw upon when developing our own emergency management response.

So, without getting too much into the nuts and bolts of what has gone before us I can assure you that what we have in place by way of a response plan to any emergency is very, very sound!

What are the key emergency management messages we deliver to expeditioners?

The first message we deliver to expeditioners is to not put yourself in danger. We do not want the rescuer to be in need of rescuing.

The second message we deliver to expeditioners is to be comfortable with change. Emergencies are dynamic. They can at times be unpredictable and are almost certain to change. No two emergencies are the same. Yes, we have templates, ready reckoners and prompt cards but they simply form the basis of our planning. The rest is up to us.

The third message I deliver to expeditioners is to slow down. Or should I shout, “SLOW DOWN!”?

Slow down, step back and assess the situation. If you do this you stand a better chance of seeing the big picture and once you have the big picture, or rather all of the available information (at that time), you are better placed to make good, sound decisions. You want to avoid making hasty decisions based on emotion at all cost. History has shown that decisions made in the spur of the moment and driven primarily by emotion often create greater headaches and place a greater demand on resources than if the decision makers had of waited until they had more of the facts. I appreciate that it is very easy to sit here and write about this stuff but I assure you I know from firsthand experience the value of slowing down, stepping back and affording yourself an opportunity to assess the situation before making a decision.

Mums and Dads will find comfort in the knowledge that each member of the Mawson team has received emergency management training. Not all, in fact very few, will ever be placed in a position to manage a major crisis (should we experience a major crisis during our expedition) but it is vitally important that every member of the team know and understand the systems and processes and more importantly they value their role in an emergency response. Additionally the tools they have been taught are applicable to any emergency no matter how large or small. Each member of the Mawson team have received this very information and have applied it in varying forms over our time on the two voyages and whilst on station.

What kind of emergencies are we likely to encounter whilst at Mawson?

Like back home on the mainland there is an infinite number of things that could go wrong. We are, after all, our very own micro city with a complicated and intricate infrastructure. We produce our own power, produce and treat our own water, have treatment plants for sewage and rubbish, we store dangerous goods and we even produce our own veggies in the station hydroponics shed. We have mechanics and builders, trucks and heavy machinery, we have a shopping centre (the green store) and we have a service station (the fuel farm). We even have our very own restaurant (the mess) with industrial ovens, freezer units and deep fryers for when the late night nibblers come to town. Then there is the Antarctic wilderness where it is cold, icy, windy and as wild, and hostile, a place as you could ever image.

The three main emergencies we plan and train for are fire, fuel spill and, search and rescue. Each team is trained to respond to all three emergencies.

Fire can occur in any one of the buildings, structures or vehicles we have on station. Over the course of sixty years, various materials have been used to construct these buildings and every expeditioner must be mindful of this dynamic when responding to a fire.

A fuel spill can occur anywhere on station however the greatest risk is at the fuel farm. There is a heightened risk of fuel spill during resupply however we have increased staff at this time to monitor and respond to a fuel spill. Every fuel spill is considered an environmental disaster and we must respond quickly and efficiently.

And finally there is search and rescue (SAR) which can be anything from a lost expeditioner on station to hauling a four and a half tonne Hägglunds out of a crevasse up on the plateau.

As I said earlier, we train to respond and manage all of these emergencies.

Who makes up your emergency response teams (ERT’s)?

Everyone on station has a role to play in an emergency.

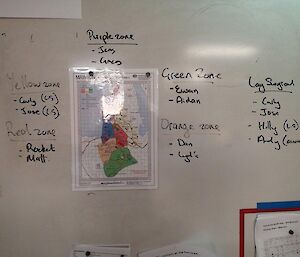

There are sixteen expeditioners at Mawson over the winter and they split into two emergency response teams with each consisting of seven expeditioners. There is an emergency response team leader, a deputy leader and five members. We have two dedicated emergency response team leaders in Heidi and Garry who are supported by two deputy emergency response team leaders in Andy and Matt. We split the trades between each team so each team has a plumber, a diesel mechanic, a communications expert and an electrician. Additionally, of the seven members at least four are trained in the use and operation of breathing apparatus (primarily for use in a fire), one is trained as a breathing apparatus controller, one is trained to operate the pump house (so as to regulate the flow of water in a fire) and one is trained to drive and operate the fire Hägglunds. As well as their core roles two expeditioners from each team are trained as lay surgical assistants. Their role is to assist the Doctor in a medical emergency.

The Doctor and I are not assigned to any one team.

My role in an emergency, that is the role of the station leader, is to act as the incident controller, responsible for the overall management off all incident activities.

The two teams work on a rotating roster, one week on, one week off and provide a 24 hr 7 days per week response. These guys are it. They are the jack of all trades. A one stop emergency response shop. There is no-one else.

How much training do the emergency response teams do?

Since arriving at Mawson we have conducted regular emergency response team training exercises. Initially when we first arrived and no-one was trained to go out into the field we concentrated on fire. As more of us ventured into the Antarctic wilderness we began to concentrate on SAR training. In between this we conducted fuel spill training.

Both ERT leaders, Heidi and Garry, and their respective teams are committed to their roles and take their responsibilities seriously. After all, our lives may depend on it. As such we conduct emergency response training most Fridays. This varies from fire training, fuel spill training to search and rescue training. Heidi and Garry coordinate the emergency response training from week to week and brief the station leader in advance.

Additionally, Doctor James conducts lay surgical training every Thursday where he rotates two of the four lay surgeons through a two hour training session each week.

What actual training do we do?

As I said earlier Heidi and Garry coordinate emergency response training every Friday. The training actually started back in Hobart, Tasmania. Some of you would be aware that we studied with Tasmanian Fire Service in Cambridge, Tasmania prior to leaving Hobart where the guys received their initial fire training from the full-time fire service instructors. This was an intensive five day course and formed the foundation of our fire response. Our fire training on station is designed to build on this foundation and primarily involves practising our turnout and response times, and muster procedures.

Due to the severe weather and freezing conditions here, we rarely allow water to flow through the systems. We did however test the capacity of the fire Hägglunds along with that of site services earlier in the year. Site services refer to the twelve fire hydrants we have distributed about the station. The data collected from this test is useful in calculating our response to a fire at various locations throughout the station.

Likewise, our search and rescue training actually started back in Hobart. The Mawsonites were treated to a one day classroom session on the principles of emergency response followed by practical lessons by our field training officer, Heidi, on knot tying and anchor systems (anchor systems are complicated configurations of ropes, pulleys and carabiners which are used to haul or lower an object, person or sled up or down a slope). Following this the team went on an overnight bivvy to Mt Wellington. On the voyages south, we continued to build on these skills where many a day we could be found setting up anchor systems in the ship’s library.

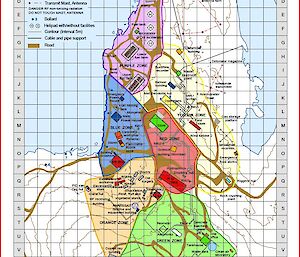

Recently we conducted a whole of station search. This exercise started with the (fictitious) report that an expeditioner had not arrived at their work station and in fact they had not been seen for several hours. Heidi and Garry planned and coordinated the response in consultation with the station leader whilst Andy took responsibility of managing communications. Below I have attached a map depicting coloured station search zones. Expeditioners were separated into two-person teams and assigned a coloured zone. The expeditioners were assigned a call sign for use on the radio and given clear instructions before leaving to commence the search. I can report the entire station was thoroughly searched and the missing expeditioner was located. He was carried by stretcher to the waiting dedicated search and rescue Hägglunds (refer photograph of green Hägglunds) and transported into the medical facility where Doctor James and his lay surgical team were waiting. At this time the exercise was completed.

More recently, Heidi has facilitated cliff rescue sessions again utilising anchor systems and she is progressively training expeditioners in crevasse travel.

Throughout the season we will continue to build on these skills.

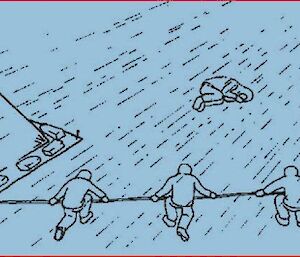

I have included several photographs (below) of expeditioners practising their map reading and navigation skills, setting up a Hägglunds recovery and Andy taking us through a lesson on use of the Hägglunds GPS and radar units. There is also a photograph of three expeditioners participating in a sweep search. Whilst you can’t see their faces (no, they are not dentists!) all three were blindfolded so as to simulate conducting a sweep search in blizzard conditions. After 30 minutes of methodically sweeping around the hut, they found the lost expeditioner — me.

So there you have it, a quick 101 on emergency response. As with last week’s brief on sea ice, I hope this story will help ease the anxiety and stress experienced by some of you back home as your loved ones venture out into the Antarctic wilderness.

Steve Robertson, Station Leader