Whilst there is plenty of birdlife that thrives here and calls the place home, occasionally other species turn up unexpectedly, as with our sooty terns earlier this year (Icy News June 17).

Digging in the station logs we find two instances of homing pigeons ending up majorly off course…

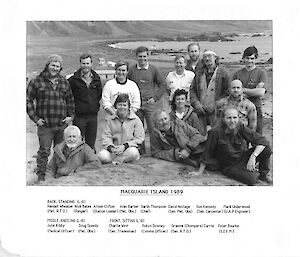

Station Log 31/10/89

A homing pigeon from Tassie flew into the store this morning. Its owners were contacted and we learnt it had been released on Sunday in Victoria… a long way for a small bird to fly in two days! It appreciated the grain and water we fed it and is now located in a cage outside the mess.

From a “A Fragmentary History”, compiled by Jeremy Smith:

This pigeon was “quite tame and lived in the main store, where it was fed. Occasionally it would take a flight outside where it was pursued by skuas, although it easily outpaced them. When the expedition’s year came to an end a few weeks later there was a strong feeling that the bird should be repatriated. The bird was caught and caged, smuggled aboard the relieving ship, fed there in captivity for three days and then released as the ship was moving up the Derwent estuary.”

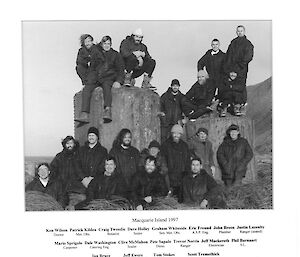

Station Log 20/8/97

Omitted to mention that a racing pigeon arrived at the station on Monday. It was banded and was captured by Mario on Monday and is now sitting in a cage on top of the piano. The band has a Hobart phone number which was called. The owner rang back this evening and spoke to Ken. He would like the bird put on the ship and send back to Hobart, It seems in good condition.

This one’s arrival made the news back home:

From a “A Fragmentary History”, compiled by Jeremy Smith:

Sydney Morning Herald, p7 — 23/9/97 — Andrew Darby

Off–course pigeon flies halfway to the Antarctic

A racing pigeon has survive an unplanned, freezing, 1500 kilometre flight across the Southern Ocean, to be recovered on the only land between Tasmania and Antarctica, Macquarie Island.

“I think I“ll call her Abelina Tasman, after the explorer, you know?”, said its owner, Mr Ken Gore. “She’s done almost as many miles as he did.”

The hen from Mr Gore’s loft on the Tasman Peninsula was released on August 18 for a race from Devonport on Tasmania’s north–west coast. With a strong north–westerly behind the flock, Mr Gore’s other birds made the 250 kilometres to Taranna in 2.5 hours. But Abelina’s pied head and blue barred wings were nowhere to be seen.

“I thought she’s been taken by the peregrine falcons or something,” he said. “She must have just lost her bearings somehow or other and just flown on.” And on. Abelina was spotted by meteorological observer at Macquarie Island, when he looked out of his hut on August 20.

After also surviving predatory local skuas and the occasional feral cat, a thin and bedraggled Abelina was caught and put in a cage.

Abelina made the trip back to Hobart on the resupply ship Aurora Australis.

Mr Gore said Abelina proved to be a capable bird before, having returned from as far afield as King Island and Wonthaggi in Victoria but he did not intend to push his luck. Now she would get a rest.

“She deserves what they always want. They want to settle down and have a couple of eggs.”