Macca may have the slowest internet speed in the world but it does have some of the cleanest air, barring a few obvious locations you should try to avoid being downwind of such as elephant seal wallows, the power house, Warren and Hass House after a big Saturday night on the black and tans.

Macca is one of the important Southern Hemisphere sites in the World Meteorological Organisation Global Atmospheric Watch program. CSIRO with BoM and other collaborators at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO), University of Heidelberg (Germany) and Princeton (USA) have been collecting air samples and measuring concentrations of greenhouse gases, their isotopes and other related trace gas in the troposphere from the Macquarie Island clean air laboratory since the early 90’s.

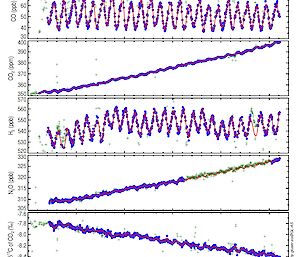

CSIRO has collected an invaluable unbroken time series of trace gas measurement data over this period. These results are presented in Figure 1, showing the steady rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) at Macca, rising about 13% since 1991 (~2 ppm per year). The current CO2 concentration in the southern hemisphere atmosphere has just exceeded 400 part per million (ppm), steadily approaching the often quoted dreaded threshold of 450 ppm.

This data is used in a wide range of global scientific research of the changing atmosphere and the impacts on regional and global climate. This includes the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) assessment reports that inform global climate agreements such as the recently ratified Paris agreement (COP21), which went into force on 4 November 2016, just after the Melbourne Cup.

I work for CSIRO Oceans & Atmosphere in the greenhouse gas observation and modelling team and this is my fourth visit to the island since 2005 but these visits have always been limited to as a round tripper during the annual V4/V5 resupply voyages.

In 2005 I installed the original insitu analyser developed by CSIRO, the “LoFlo” to measure atmospheric CO2 continuously and very precisely. This has produced a continuous decade long data set that is currently being used to investigate the potential decreasing efficiency of the Southern Ocean to absorb atmospheric CO2. I have been busy developing an international collaborative network of well inter–calibrated atmospheric observation sites for this purpose and which Macca and Cape Grim form the hub (Figure 2).

The Southern Ocean is one of the most important natural CO2 sinks. The global oceans remove from the atmosphere an equivalent amount of fossil fuel derived CO2 as the terrestrial biosphere does. And here are some more facts and figures for your next trivia quiz night: there is more carbon stored in the deep ocean than in all of the reservoirs of carbon on earth combined… and penguins are one of the only vertebrates that can’t taste all of the five different flavour classes–sweet, bitter, sour, salty and the savoury taste, umami. So when they throw down all those fish they can only taste the salty and sour components.

I am here on Macca until VMI to use all five of my taste sensations for a very short summer, possibly longer depending on how long the L’Astrolabe takes to get here. The main objectives of this visit are to 1) Install a new air sampling mast for the clean air lab and 2) upgrade the ageing CO2 analyser with a new technology analyser (Picarro, USA), which uses the unfortunately named Cavity Ring Down Spectroscopy (CRDS) technique.

Following in the footsteps of my Lidar obsessed mentor Andrew Klekociuk this CRDS technique is also laser based with just as many potential real world applications as the more fancied Lidar, including the holy laser grail for full body laser sculpturing of Hollywood celebrities.

So the new analyser is in and operating well, currently it is being cross calibrated against the old LoFlo system. And the new air sampling mast has also been successfully installed and is now running after a very long gestation period getting capital expenditure funding and approvals done across three agencies.

A big thank you for everyone on site here who did all the actual work welding, digging, moving and of course the erecting team who took all the glory: Horse, Nick and the Greg family. This shiny new mast has caused quite a stir on the island with signs of tower envy emanating from some circles (there is always one in a crowd). For all the other people on the island, don’t be shy, feel free to come down and get your picture taken with the new island star attraction, a great one for Macca scrapbook (Figure 3).

There was much learnt from putting up this tower and as always an element of personal growth. From the trades team I learnt about important AAD procedural steps such as JHA (job hazard analysis). I also learnt a great deal about new construction concepts such as how when an observed 1 –2mm off a perfectly level surface can be described as “allowing for windage”.

In particular, I learnt a lot from the sifu (master) of stainless steel, Horse. The most significant being the correct terminology for the unistrut spring washers which are used in the mast construction as “Mr. Zeppity’s”, apparently named after a kid’s cartoon character on the slightly psychedelic named “Magic Roundabout” show, a particularly springy one I presume.

Dr. Marcel van der Schoot