A challenging week for intrepid photographers with the Aurora Australis in the southern skies

With recent significant solar flare activity recorded on the sun’s surface, we have been treated to some beautiful auroral activity as a result. First, before we see what later unfolded above us, let’s look at a little of what we understand about the sun and its effects on our atmosphere.The sun gives us more than just a steady stream of warmth and light.Situated 150 million kilometers away from us, the sun is a huge thermonuclear reactor, fusing hydrogen atoms into helium and producing million-degree temperatures and intense magnetic fields.Near the surface, the sun is like a pot of boiling water, with bubbles of hot electrified gas. The steady stream of particles blowing away from the sun is known as the solar wind. Blustering at 1.5 million kilometres per hour, the solar wind carries a million tons of matter into space every second.

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) and flares can occur several times per day with some of them aimed in the earth’s direction. Fortunately, Earth is protected from the harmful effects of the radiation and the hot plasma by our atmosphere and by an invisible magnetic shell known as the magnetosphere.

Produced as a result of the Earth’s own internal magnetic field, the magnetosphere shields us from most of the sun’s particles by deflecting them around the earth.

Auroras are caused by CMEs or gusts in the solar wind that will push on our magnetosphere so that particles inside the magnetosphere are injected into the earths upper atmosphere where they collide with oxygen and nitrogen. These collisions, which usually take place between 60–300km above ground, cause the oxygen and nitrogen to become electrically excited and to emit light (fluorescent lights and televisions works in much the same way). The result is a dazzling dance of green, blue, white, and red light in the sky.

It is these collisions which generate the beautiful lights which are observed as the Aurora. The patterns and shapes of the aurora are determined by the changing flow of charged particles and the varying magnetic fields.

Aurorae are most commonly visible at high north or south latitudes. However, at times when the earth is most affected by activity on the sun, they can be seen at lower latitudes. In Australia, aurorae have been seen on rare occasions from as far north as southern Queensland. But they are much more likely to be seen from the south of the continent.

Aurorae in the southern hemisphere are commonly called the southern lights; or more technically the Aurora Australis.

To be lucky enough to see the aurora is indeed a beautiful experience, as the well known

Austrian explorer Julius von Payer (1841-1915) once put it: “No pencil can draw

it, no colors can paint it, and no words can describe it in all its magnificence.”

For many who have observed the magnificence of the Aurora however, there is this untameable urge to attempt to capture it either through the eye of the lens or reproduce an image of the pulsating energy it displays through colour.

A few tips from one of our intrepid types out and about this stunning evening:

How to take photos of aurora on Macca by Leon H

- Check with the nearest website or comms tech about solar flare activity or radio static and find out when an aurora is likely. If need be, continually harass the comms tech into making a solar flare happen.

- Keep a careful eye on the weather and hope the cloud cover clears for the evening. Usually bribing the Met staff helps

- Make sure your camera has been prepared earlier in the day as setting up the focus for distance is pretty hard to do at night.

- Once there’s a clear night, continually check outside to see if the aurora has started. Sometimes there’s a little shimmer in the sky earlier in the evening, but the main show doesn’t start until much later. So have a nap, set the alarm (or drink lots of coffee) and follow the old motto of hurry up and wait.

- Before the aurora is at its best, either try to sweet talk the ‘dieso’ or ‘sparky’ into turning off the street lights or go for a quick little walk to somewhere with less light such as the Ham Shack (or maybe up North Head). Take a torch, tripping over things can be painful.

- Now go back to your room and get your camera then make sure you have the widest lens you own attached and find somewhere out of the wind. If you're lucky, there will be other colours in the aurora.

- Point the camera at the most interesting bit of the sky, and start taking photos. Remember to have a low sensitivity (ISO), really wide aperture (the lower the f value, the wider the aperture) and a long exposure.

- Hope that you camera is at least vaguely in focus. And when the battery cuts out, go back to your room for the spare and then try again.

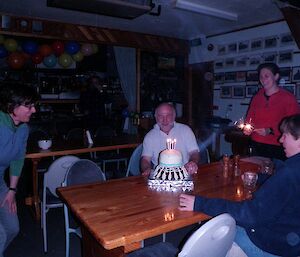

- Go to the mess and make a coffee/Milo/tea and brag to your fellow expeditioners about how good your photos are going to be.

- A little bit of work on the photo (maybe a little brightness or some such thing) and you'll have the best photos on station (plus something pretty to hang on your wall).