Planning an Antarctic adventure: “Do you get to leave the station?”

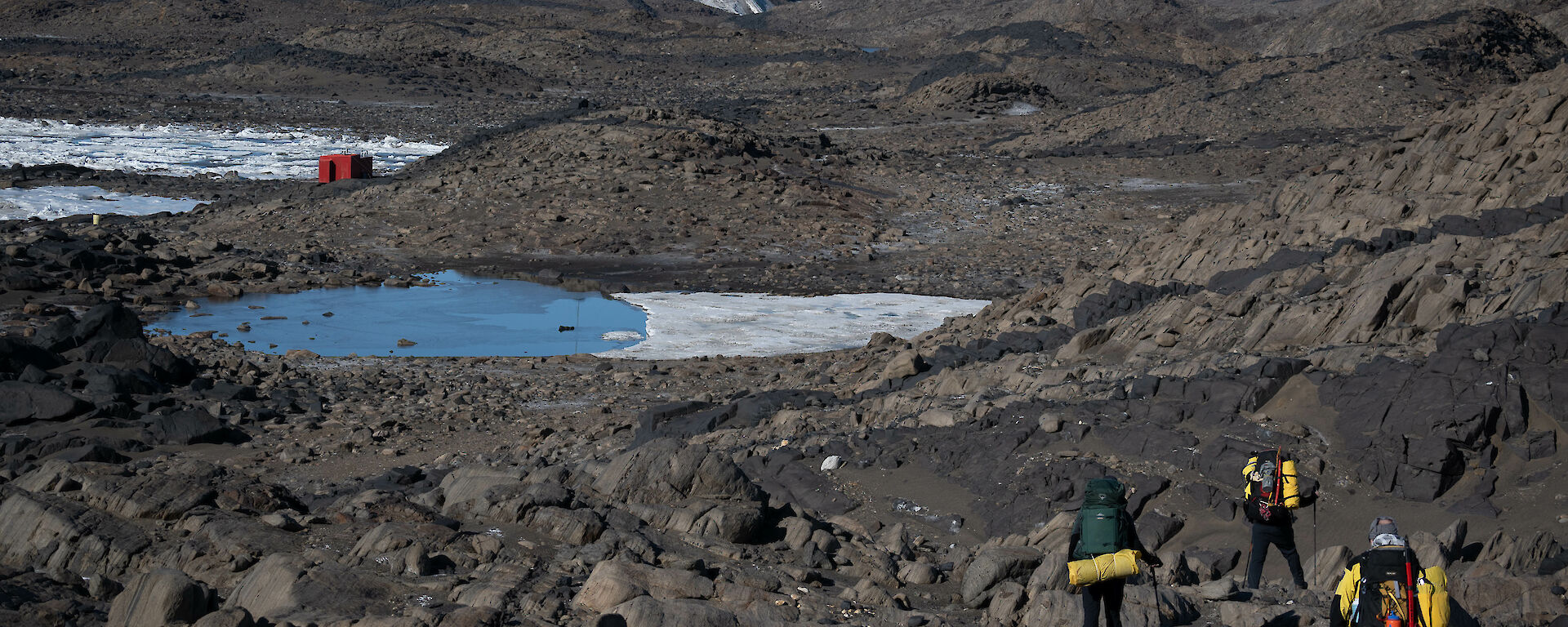

I’ve found this to be a common question from friends, family, and prospective Antarctic expeditioners. Many people quite reasonably expect that that given how remote and inhospitable Antarctica can be that the answer may be ‘no’. Yet in the seven months since arriving at Davis Station I’ve been on seven overnight trips off-station, for 11 nights away in total, as well as numerous day trips off station. Most of these adventures have been recreational, searching for awe-inspiring vistas of the Vestfold Hills, chasing auroras and exploring valleys of hypersaline lakes.

Indeed, for all the deprivations that Antarctic life comes with, expeditioners with the Australian Antarctic Program (AAP) have extraordinary latitude when it comes to leaving station in search of adventure. Few others that come to Antarctica, whether as part of other research programs or even as tourists, have the same degree of freedom to explore this frozen continent. It’s a defining feature of the AAP, and one that stretches back to the early days of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE). However, as with all privileges, the freedom to leave station comes with responsibilities and meeting these requires planning and training.

An off-station trip requires the right combination of trained and available personnel, travel routes and communication plans, and vehicle and accommodation availability. If, as an expeditioner, you wish to organise a trip off-station you’ll first need to make sure that all trip members have completed the appropriate level of training. Survival training from the Field Training Officer will do for general trip members, but you’ll also need an approved Trip Leader. Trip Leaders need to be approved by the Station Leader in consultation with the Field Training Officer, and can only apply after completing field travel training and three off-station trips. Once you’ve been approved (or recruited a Trip Leader), and everyone has completed the appropriate field training, you’ll all need to make sure you’re actually available on your planned trip dates.

Life on an Antarctic station never stops – not for weekends or holidays – and so even outside of normal working hours there’s a plethora of rosters that need to be covered. Trades on-call rosters, fire team rosters, Saturday duty rosters, slushy (Chef’s assistant) rosters, hydroponics rosters, rostering rosters (ok, maybe not the last one). In practice though it’s usually straightforward to trade rosters with another expeditioner. What goes around comes around, so swapping rosters often means both parties can be available for trips when they want to be.

So far, so good. You’ve got a group of trained expeditioners eager to go, and everyone’s available for the trip dates.

Next, you need to work out your destination and travel route – and have a backup in case of unforeseen obstacles. Within the limits of the Station Operational Area surrounding Davis Station there are 11 field huts (complete with bunks, heaters and ovens), a handful of field caches (containing tents and extra camping equipment), and a limitless number of spots to pitch a tent (depending on your tolerance for discomfort). Depending on your mode of travel, some of these can be reached within a couple of hours, some will require multi-day trips with stops along the way. You’ll need to plot a route that navigates around cliffs and lakes, avoids Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs), and accounts for travel speed. Unfortunately, even if you’ve plotted a perfect route on the map, you still need to account for weather. Antarctic weather can be fickle and dangerous: sunshine and gentle breezes one hour, and blinding snow the next. Your Bureau of Meteorology colleagues on station can offer helpful insights into forecasting the weather, but incorporating bad weather contingencies is critical to any field trip plan. Once you’ve got a draft plan, run it by the Field Training Officer to get their feedback, and incorporate any changes they suggest.

Field trips also require a communications plan. Our field trips are all run with the PACE communication methodology, which stands for Primary – Alternative – Contingency – Emergency and outlines a series of communication systems that will be tried to contact station. If the first system doesn’t work, then you try the next, and so on. Here at Davis Station this often means taking a VHF radio (Primary), a satellite phone (Alternative), a satellite tracker with text message capabilities (Contingency), and a Personal Locator Beacon (Emergency).

You’re getting there: you’ve now got a team, a travel route and a communications plan.

Now you need to obtain approval for any vehicles you wish to use. All field trip vehicles require additional training, and operational needs and maintenance schedules will mean vehicles aren’t always available. Field huts have limited bunk space, so these also need to be booked – no need to worry about this if you’re planning on camping though. Finally, you need to pull all this together into a Field Trip Application for Station Leader approval. They might come back with comments and suggestions, and the weather can always interfere with a trip at the last minute, but otherwise you’ll be good to go! All that remains is to pack your bag and actually follow through on your plan…

So, go lodge that trip application. Chase that aurora, visit that historic cairn, explore that frozen fjord. Antarctica is out there, and all you need to see it is a little planning.

“It is in our nature to explore, to reach out into the unknown. The only true failure would be not to explore at all.” – Ernest Shackleton

Joshua Biggs

Supply Officer / Fire Chief

Davis Station

77th ANARE