One of the advantages of being a Met Tech at Casey station, is occasionally we get to go to some special remote places for work.

Casey and the surrounding area is home to eight automatic weather stations that require servicing. Some are a Hagglund drive away, some can only be accessed by light aircraft, and one is even a three day round trip.

One of those special places is the Browning Peninsula. It is the third peninsula south of Casey station. Jutting out into the Southern Ocean, along with its islands, it is sandwiched between the Peterson Glacier and the massive Vanderford Glacier. It’s about three or so hours from Casey by Hagglund over the Peterson Glacier. If you get there any faster, you will have a very unpleasant ride bouncing over sastrugi (wind sculptured snow) that sits atop the hard blue glacial ice.

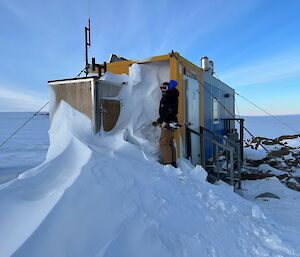

The weather station here is located on top of a rocky hill with spectacular views of the surrounding glaciers. It is also cold and very windy! Due to the shorter daylight hours from late autumn to early spring, we had to time our arrival and plan well to get the servicing job done in the light. Although we had made good progress with our work and still had more daylight, before we were finished we were chased away by increasing winds whipping up the snow from the ground. As the weather was looking worse in the distance up on the glacier, we retreated early to the nearby hut where we had planned to stay for the evening. Some digging was required to get to the loo!

One of the things I find wonderful about being an expeditioner in Antarctica, is spending quality time getting to know my amazing companions, exchanging experiences and listening to life stories, in some of remotest places on the planet. That night I shared the evening with my fellow Met Tech Bruce and our station doctor Sophie. Their company certainly didn’t disappoint.

The next morning, after reading some entires in the hut log, and writing our own, we tackled finishing our maintenance job. I was doing the final calibrations, typing on the laptop keyboard using a pencil so I could keep my gloves on in -22 degrees, when snow and ice started blowing onto the keyboard! Job done, time to leave!

After a particularly busy and tiring summer this season, outings like this create memories that I will cherish forever.

Shaun James

Senior Met-Tech, Casey station