As I come to consciousness, it's clear that strong winds we expected this morning have arrived. It probably won't be suitable for solo travel, and last night I organised a 'Casey Uber' to get to work.

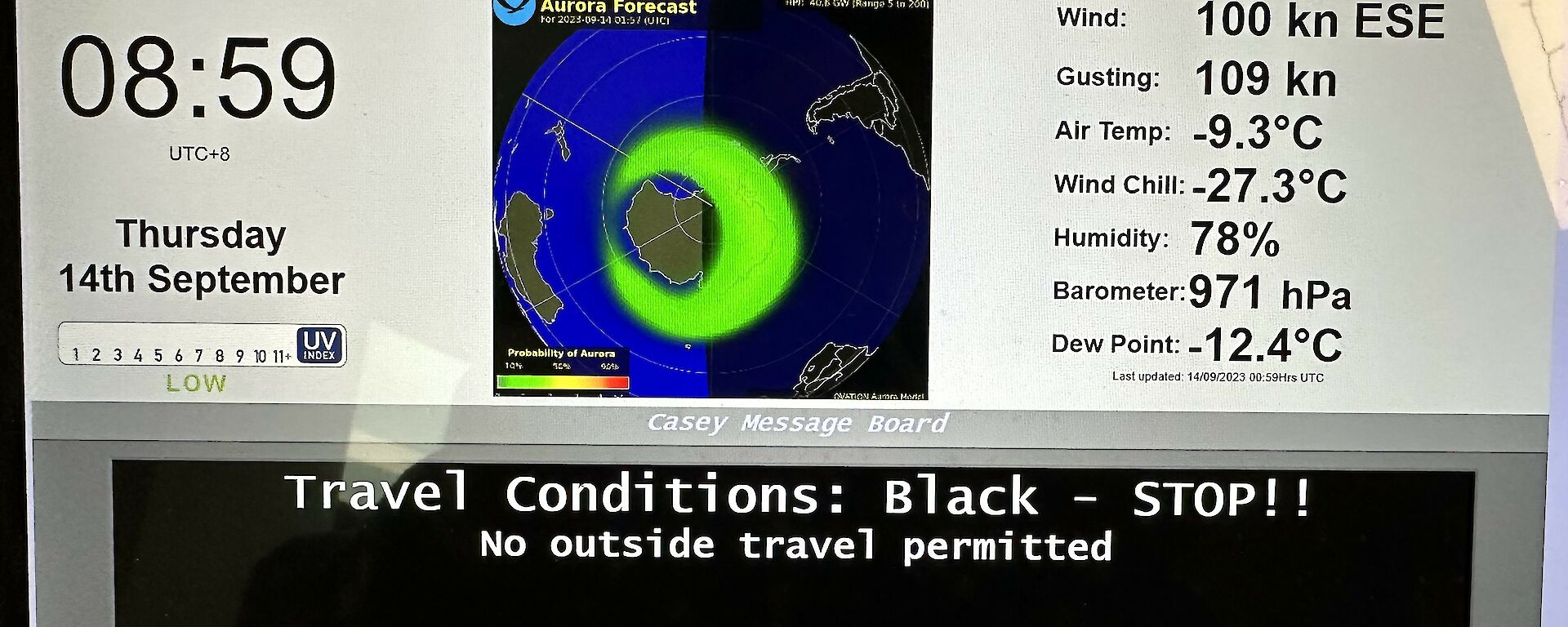

Sleepily, I look at the weather display on my room phone. I squint, double take. Sure, I've just woken up, and admittedly I'm on the way to needing glasses. But the mean wind speed number appears to start with a 9. 90-something knots. More than 166 kph! And the gust speed is in three figures. 100+ knots – more than 185 kph!

After a few minutes thinking, I decide it's not safe for me. I'm sure my two strong Uber drivers would do their best to stop me blowing away, but in this weather they'd be working hard to keep their own feet on the ground. Even if I could get to the Met Office, the chances of a successful weather balloon release (usually my first task of the morning) are virtually nil. I send a cancellation message to my Uber, Tim and Nick.

I do some work tasks as best I can from the Red Shed, joining in now and then with the community photography of our weather displays as we break some records for the year, then the season, then the past few years.

In the afternoon Sophie, our doctor, finds me.

"It's Mabel," she says.

"I think her mast has come down."

Mabel is a hut - anthropomorphised by me - which houses air sampling instrumentation for our Greenhouse Gases in the Southern Atmosphere program, a research program that's been run for over 40 years by the CSIRO's GasLAB in Melbourne. There's continuous sampling for carbon dioxide, methane and water vapour, and we also regularly fill glass flasks with air which is then analysed for those gases and about 15 others (some of which I'm not sure I'd heard of before I started this job).

Sophie and I peer out of the southern windows of the Red Shed through the sheets of snow. Something is definitely wrong. Mabel's distinctive air sampling mast has gone.

A day and a half later the station takes a collective deep breath and starts to survey the effects of the storm. Unfortunately, they are substantial, especially in areas outside the core of the station. The loss of Mabel's mast is impactful scientifically, but it's by no means the most severe damage.

My workmate Bruce walks up to Mabel. Her mast has snapped clean off close to the base. One of her corner guy wires has broken out of its ground anchor and the other guys are worse for wear. Miraculously, the air sampling lines appear intact. The inside of the hut looks as if a giant has shaken it. The supervisor PC for the air sampling spectrometer is off the bench, held only by its ethernet cable. But another miracle - no serious damage to the instruments.

Bruce takes photos and sends them along with his damage assessment to CSIRO in Melbourne. The next day he and I return to rig an interim strap-down for the broken mast and tidy up the rigging as best we can.

Showers of paint flakes inside Mabel speak to the force of the shaking but to Bruce's and my eyes the hut itself seems intact. Our AAD engineering and building services colleagues undertake structural inspections and declare that Mabel is safe to work in and structurally undamaged.

I am grateful and (completely unjustifiably) proud. I didn't build Mabel but she just weathered a storm that made us all remark that we weren't in Kansas anymore, Toto!

Sadly, the dismasting means the air sampling set up is not serviceable. So, with the help of a checklist from the GasLab staff I make my way back to Mabel to turn off all the instruments. It was a sad task. I have never been in the hut without the familiar hum of the air pumps and now the Antarctic silence is all too profound.

However, in a wonderful demonstration of collaborative effort, several teams are in action. The GasLab staff in Melbourne are sourcing a new mast and other spare parts, arranging for them to be flown down when our aviation season starts. The AAD trades staff carefully remove the broken mast from the roof and blank off the sampling lines. Bruce and the GasLAB staff discuss a temporary set up. What if the top section of mast, on which the sampling cups are still mounted, could somehow be fitted to the mast stump? Maybe - but the two sections would have to be joined somehow, and they're not the same diameter.

Enter Brenno, our communications technical officer, and his 3D printer. In a matter of days, a precision-made bright yellow mast collar is ready to be fitted and on a glorious bluebird morning, Bruce and Brenno head up the hill to jury rig the mast.

(As an aside, I am not sure how Casey would have functioned this year without Brenno's 3D printer and his expertise in using it. We have benefited from a huge range of industrial, technical and domestic items, including a replacement for a cutlery basket which bewilderingly vanished overnight, leaving the teaspoons homeless.)

We have a bit of a blow (a severe gale by Beaufort Wind Scale standards, but simply a not-very-nice-weather day by Casey standards) and it's a good test. Everything holds up well.

We have the go ahead from our GasLAB colleagues to restart sampling. I go up to Mabel and slowly, carefully, turn everything back on. This is the acid test. Will everything run normally? Will it even power up? Yes, it seems. One machine won't respond to remote log in attempts from Melbourne. Internal damage? A cable wrenched in the storm? No, something far simpler thank goodness - a power supply unseated by a fraction of millimetre, invisible but responsive to a good old time-honoured cable-wiggle.

It'll need a few days for the GasLAB staff to watch for anomalous readings, but all looks good so far.

The next day the wind is blowing from the south and happily this means I can do a flask fill. I set off up the hill and think about the article I wrote earlier this year, and the children in my thoughts as I wrote it. My niece and nephew, my friends' children, the generations coming after us. This data is important for us and for them.

The flask pump unit is pretty robust, but we don't know for sure how it fared in the storm. I set up the fill and start it going. There's a tell-tale change of machine tone as the fill comes to an end, and I think I actually hold my breath, willing the green 'good sample' light not only to appear but to stay on steadily and confirm a good run.

It does.

We're officially back up and running. This precious data is flowing again after one of the shortest externally forced breaks in the project's history. A testimony to the hard work, ingenuity and dedication of many people.

And fittingly, today is my nephew's birthday.

Clare Ainsworth, BOM Observer and Friend of Mabel