This week at Macca, the fantastic and intriguingly-titled paper “Antarctica’s wilderness fails to capture continent’s biodiversity” (2020) written by a team of Monash researchers and two members of the AAD’s scientific department, and subsequently published in the prestigious journal Nature, has been sparking fascinating discussion. The following musings are merely reflections and ideas on the enduring allure of the Antarctic regions, and how best to preserve them for posterity.

Since the days of Wordsworth, Coleridge and Keats, a romantic fascination with natural places has been a key component of western aesthetics (Turner 2002). This tradition continues today, as the burgeoning ecotourism and wildlife photography industry in the Antarctic Peninsula attests. These aesthetically and experientially driven industries - and their attendant impacts - highlight the ‘paradox of popular wilderness’ (Turner 2002); that due to overuse, recreationalists have been in danger of ‘loving their wilderness to death’ for many years (Nash 1967). Indeed, the very idea of ‘untouched’ or ‘virgin’ wilderness areas has been mortally wounded by the withering critique to which they have been subjected in recent years, being replaced by a more complex and realistic understanding of our impacts on a global scale (Sessions 1995, Calicott and Nelson 1998). This newest research expands on this understanding, bringing to our attention that even Antarctica, that great untouched land, may be more ‘touched’ than we care to admit. This despoliation of natural places by those who wish to enjoy and experience - or even research - them, was originally examined by Roderick Nash in 1967, and launched what is now referred to as ‘the wilderness debate’.

More recently, William Cronon’s (1995) influential article: The trouble with wilderness, written contemporaneously with the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (1991), sparked what is now referred to as ‘the great new wilderness debate’ (Callicott and Nelson 1998). In this debate, the legitimacy of wilderness is not questioned, but rather its use, purpose and role in the modern world. One such ‘role’ is proposed by Kahn (2002), who suggests that ‘environmental generational amnesia’ may be to blame for the fact that many people, whilst holding environmental perspectives, may not actually recognise the damage surrounding them. Hence, wilderness - and in particular Antarctica – may serve as an important gauge by which to re-examine and recognise the world in its original form, and to connect this new awareness to the environmental damage we daily witness at home. If we begin to understand our role as a species within, as opposed to external to, and dependent upon, versus antagonistic to nature, we will massively restructure our relationship with the natural world. This tacit idea is seen in E.F. Schumacher’s assertion that ‘modern man talks of a battle with nature, forgetting that if he ever won the battle, he would find himself on the losing side’ (1973, p.78). This has been especially clear in the years since 1973, when the threat of anthropogenic climate change, amongst other ecological exigencies, has made the issue more palpable and pressing. The way we value, manage, and protect Antarctica clearly has massive implications for worldwide environmental outcomes.

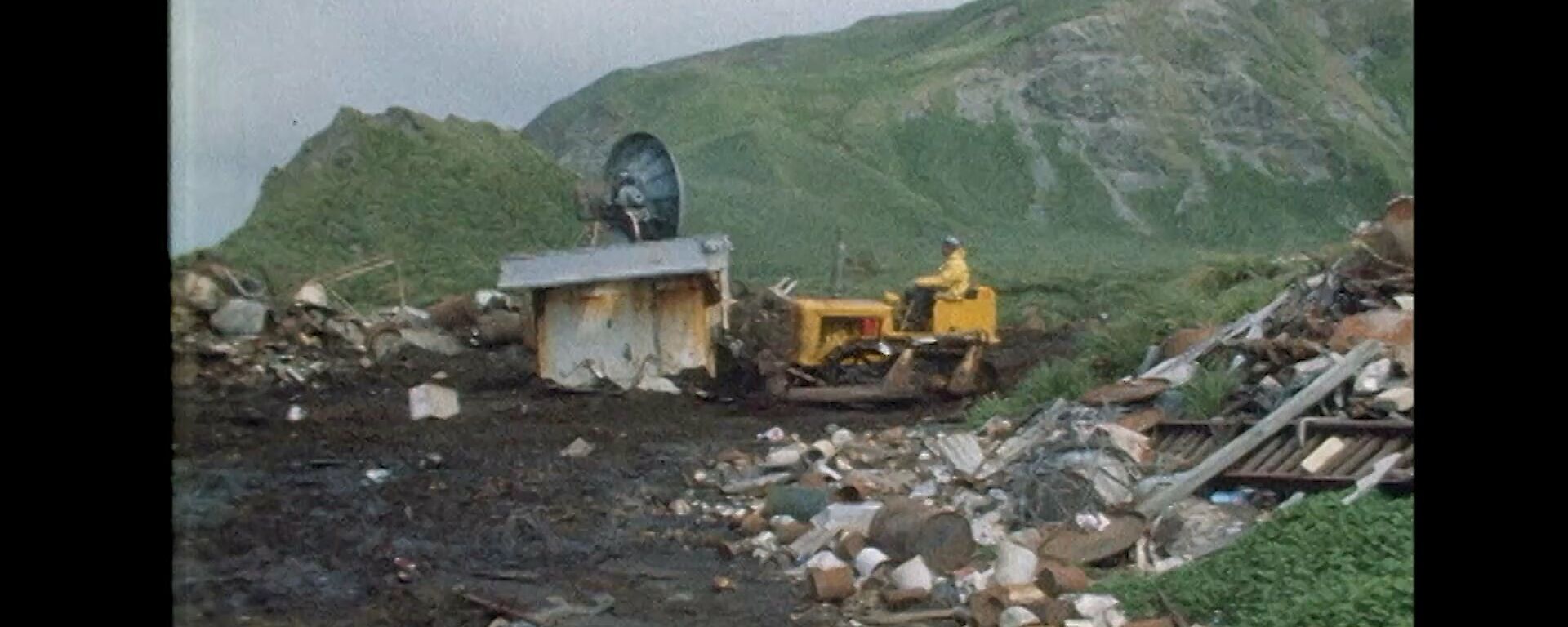

Macquarie Island is slightly unique, in that whilst not being subject to the Antarctic Protocol, it shares a common history of human habitation patterns, impacts, and rehabilitation. The internationally standard-setting work conducted during the Macquarie Island Pest Eradication Program (MIPEP) of 2011-2014, has shown a commitment to the restoration and rehabilitation of the lands under our collective stewardship. I for one, heartily welcome the benchmark of high-quality scientific understanding to inform and validate the creation of specially managed areas that protect our valuable ecological heritage. Hopefully such places can continue to remind us of our place in the natural world, our dependence upon it, and the dazzling beauty of untrammelled lands.

Alexander Dylan Thomas, Environmental Officer