It’s an exciting time of year for the albatross team on Macquarie Island as the light-mantled, black-browed and grey-headed albatross eggs are hatching and the wandering albatross are returning to breed.

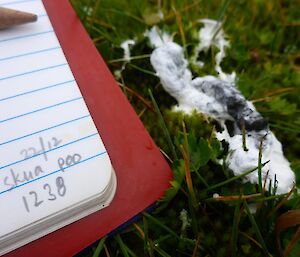

Field biologists Penny Pascoe and Kim Kliska, along with assistance from the wildlife ranger Marcus Salton, have been out and about monitoring the hatching success of these species. The albatross and giant petrel program contributes data to the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatross and Petrels (ACAP) to develop an understanding of the global population trends of these species. Towards the end of December the black-browed albatrosses were the first to be heard and then seen hatching. Grey-headed albatross were next, and by late December/early January, light-mantled albatross chicks have been spotted.

One parent will remain with their chick guarding them from predators while the other forages for food to return to the chick. Once they grow and can defend themselves, both parents begin foraging trips and both feed the chick until they fledge the nest in late March/early April. Seeing cute bundles of fluffiness squished under their parents or sitting tall on their nest ‘stacks’ has been a highlight of recent fieldwork.

The largest of them all, the wandering albatross, have been returning to court, mate and lay eggs. The chicks from 2016 all fledged by late December, around the same time that male wanderers were spotted returning to the island to begin nest building for their life long partners or to attract a mate. Wandering albatross mate for life and it has been interesting observing known partners returning to the island and new pairs forming. With only five eggs laid last season, and low numbers breeding on Macca, every egg counts towards the survival of the population on Macquarie Island.

Kimberley Kliska