The sinking of the Nella Dan is, unfortunately, just the most recent in the history of shipwrecks on the island. In fact, the first visitors to the island were most probably shipwreck victims.

As the sealing trade took off and traffic to the Island became more regular, records of incidents were kept. Early recorded casualties include the Campbell Macquarie in 1813 and the Betsey in 1815. The sealing vessel Caroline was wrecked in the area now named after it, Caroline Cove, in 1825 after being swept ashore by a storm. Inevitably the weather is almost always to blame.

On November 10, 1898, the Gratitude, a long time visitor to the island and considered one of the finest vessels working the area, was washed ashore in a storm with waves so high that she ended up missing the reef completely and beaching herself. Her crew were all safely landed and worked hard to save what supplies they could and what was left of the cargo. Rough weather continued and late in November waves threw the wreck above the high water mark, smashing the boat up at the same time. When the ship did not return to New Zealand on schedule, the Tutanekai was sent to Macquarie to see what had happened and arrived February 17, 1899 to rescue the shipwrecked crew, all the whom survived the ordeal.

Not all were so lucky. On December 20, 1910 the Jessie Nichol hit the rocks at the Nuggets. Most of the crew were sent ashore, a trip that took about an hour of steady rowing through the gale, and upon finally arriving at the beach the boat overturned, filled with water and couldn’t be relaunched. The Captain, First Mate and Cook had elected to stay with the ship and sadly perished when the boat couldn’t be sent back out for them. The ship itself broke up on the rocks.

On December 28, a passing vessel Ida. M Clarke, called at the island and offered to take the survivors with them to the Campbell Islands. As they had sufficient provisions, the crew of the Jessie Nichol elected to stay and weren’t rescued until the Huanui came to pick them up in March, 1911. But not all of them were ready to leave: five of the men were enjoying island life enough to elect to stay on for another three months for the elephant seal season.

These sealing gangs weren’t having much luck though, and the vessel sent to relieve these five volunteers and resupply the next sealing crew, the Clyde, was also hit by storms upon arriving at Macquarie Island and she dragged on her anchors and was blown close to shore. Three crewmen rowed ashore through turbulent seas to announce their arrival to the five men living at the camp. The men all set to work unloading stores hoping for a quick turnaround, however the wind turned easterly and the surf increased — a tell for an encroaching storm for those that knew the island weather, which this captain did not.

For three days a gale blew, and, despite the desperate efforts of the captain and crew, the Clyde struck a reef and ultimately washed ashore, however all crew were safely landed after a tremendous effort by the shore crew. The wreck offered additional supplies to those men working the island and they stripped her of everything they could that would improve the quality of their lives, including sails, running gear and surplus stores. The kitchen stove was taken ashore and installed in their hut, whilst the increase in rum rations was welcome indeed!

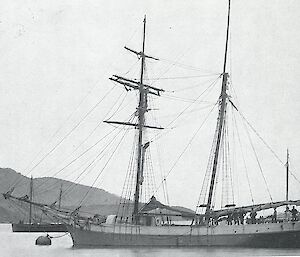

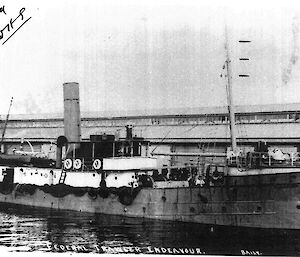

In 1914, when visits to the island had commenced for purposes other than oil and skins, the Australian Government science research ship, S.Y.Endeavour, was sent to the island to relieve the current meteorologist living on the island and conduct research into fisheries. The ship arrived at Macquarie Island in poor visibility after a rough voyage from Hobart. The weather station was handed over and fish were trawled for and collected — some species of which had never been seen by the ship’s biologist before.

On the morning of December 3, 1914 the Endeavour left the island in a heavy fog and was never seen again. Powered by steam, with sails as a backup, the ship was thought able to weather most conditions and the authorities held no grave concerns at first. A number of search vessels were dispatched to search for the ship but found no trace of the vessel in the seas she was believed to be in. The search was finally abandoned on February 6, 1915 and a later inquiry resolved that the ship foundered in a gale and all 23 men on board perished, including the home–coming meteorologist Harold Power with all the data from his year on the island.

The mystery shipwreck of the island, or stuff of legend if you prefer, is that of the Eagle, a ship believed to have been wrecked on the west coast sometime in the 1860’s and of who’s voyage there is no verifiable information.

In 1877, two crewmen from the (also shipwrecked) Bencleugh, went for a walk around the island and came a cross a ship’s figurehead of a large eagle at what is now known as Eagle Cove. Four months later, the cove was again visited and it was noted that there was a cave which looked like it had once been inhabited, presumably by the survivors of a shipwreck, as there was wreckage on the beach to go with the figurehead. The legend grew in the retelling and by 1947 the Adelaide Mail reported: “In the 1860’s a brig was wrecked off the promontory later named Wireless Hill. Nine men and one woman got ashore through the mountainous combers and lived for 26 months in a wet, shallow cave before they were rescued — gibbering skeletons, draped in blistered skin, their hair matted and their teeth loose with scurvy… The female died the day the rescuing sealer hove in sight.” Wireless Hill and Eagle Cave are not close enough to each other for this story to mesh seamlessly with that earlier account of wreckage on the beach by the cave, but of such things are legends made…

Compiled with information from “Macquarie Island” by J.S Cumpston and the TasPWS website. http://www.parks.tas.gov.au/fahan_mi_shipwrecks/journals/Shipwrecks/shipwrec.html