What do you do when your tractor is broken and the postal service doesn’t have an icebreaker available to deliver spare parts?

Well, at Casey station, we jump on the phone to the Air Force and ask them if they wouldn’t mind picking up a couple of spare parts and throwing them out of the back of a plane for us.

That’s exactly what happened this month when it was found that two out of the three snow blowers used to prepare the ice runway at the end of winter failed. One was in poor condition, the other, catastrophic.

We were warned that the parts delivery would be “just an air drop – pretty much it happens then it’s over.” However, we’re still remembering and talking over the intricacies of this spectacular operation.

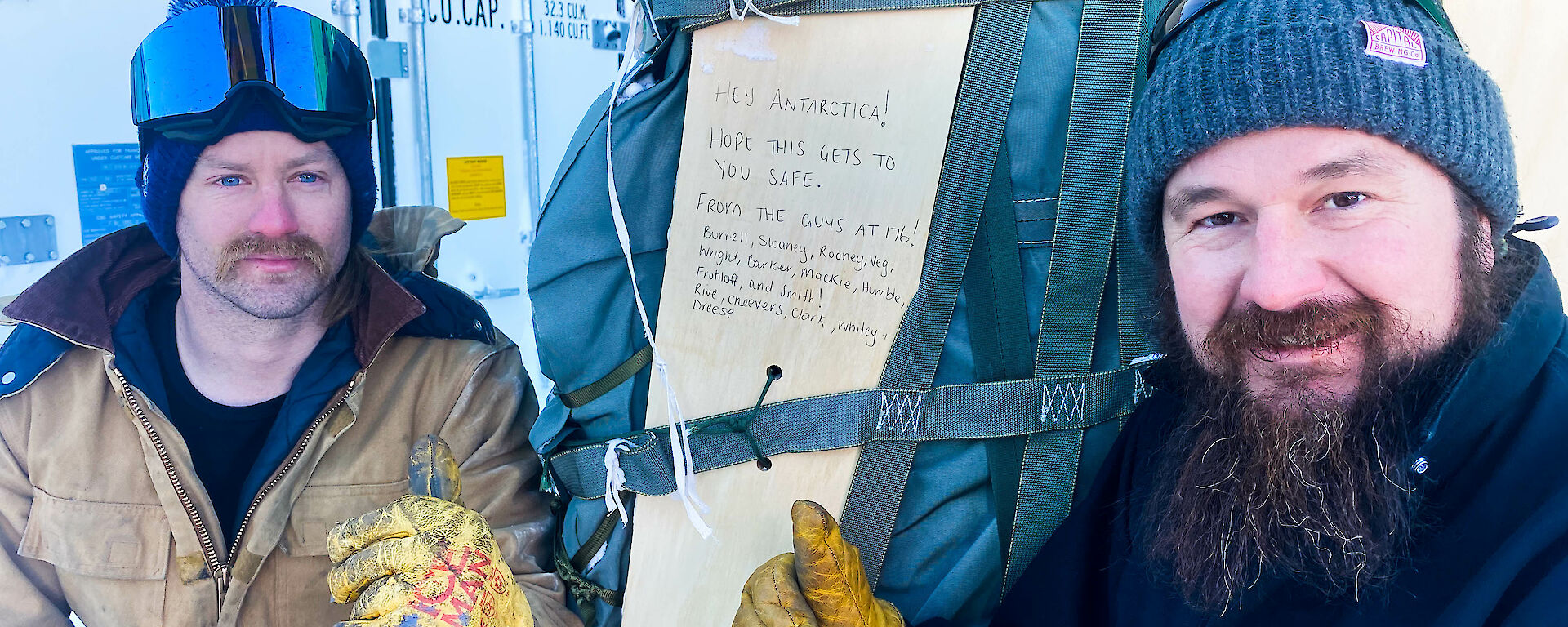

Apart from confirming part numbers, specifications, load weights and dimensions of the all important spare parts, it was also crucial to collect a few important space fillers to ensure the cargo did not rattle around. This consisted of chocolate, cling wrap, mail bags, and a few other items from the “if you have space for it” list.

The next order of business from Casey’s perspective was the formation of the drop zone crew, observers crew and station crews to stay back and cover standard Fire Team and Search and Rescue positions. (These teams are rarely called upon, but due to our self-sufficient status in our little isolated home, they are always on standby.)

Work tasks for the day were shuffled to allow the provision of compressed training to the receivers and communications personnel. But of course, nothing goes 100% to plan in Antarctica. This was proven when my morning tea break was interrupted as I, not formally trained in communications, learned that the Zetron Communications interface incorporates a phone line of sorts, and how to answer it. I rapidly assumed the position of "Mission Control" (as I like to think of it) and began rattling off facts and figures for the latest update, frantically scratching down latitudes and longitudes, followed with numbers in “Zulu” time. I relayed the info back to the operator: the Stallion was on track and on time, and the drop zone crew were at the ready, having rolled out the “We are go” blue tarp to signal the pilot.

Over the gentle hum of our station power generators, the roar of our C-17 delivery transport began to rise. A grey shape took form in the sky, which I went out to meet with my camera.

My borrowed 600mm full frame lens was zoomed in … then out … then in … Is the auto focus working?… I’ll turn it off … Rapid induction photography lesson aside, even the station crew could see the aircraft now without artificial assistance. I managed to sort out my giant piece of machinery (this lens weighed a tonne and I’m sure would have required a much bigger aircraft to airdrop it – sorry Barry).

We witnessed the aircraft surveying the ground conditions and saw the rear door open on the final approach. Seeing two squares fall out and the parachutes deploying through a magnified lens was an impressive sight. To know that the critical spares needed to secure our way home were contained inside those packages was an elating feeling, I can tell you.

I watched them gracefully lower to the horizon, then returned my attention to the plane's fly-by over the station as the RAAF turned and headed for home. It was time to haul my overweight camera equipment inside and get back to work. The makeshift mechanical team however had a big night ahead of them!

The snow blowers have since been repaired and tested. Now we just have to wait for some clear weather for our Wilkins team "up the hill" to prepare a very flat piece of ice for the summer's first flight to land on, so we can hand over to the incoming crew and then head home.

As we enter our final few weeks, this is going to be one of the memories that will come to the front of my mind when people ask, “What was it like living in Antarctica?”

-Brenden Sainty (Electrician)