'Still no word if we're flying today.'

The situation is tense as Lenneke updates the ICECAP team over coffee and leftover birthday cake in the Casey mess.

'We'll find out more at the weather briefing at noon.'

Hours tick by and breakfast turns to smoko as we wait, not knowing what kind of data we'll collect today, if any at all. Will the gravity meter cause headaches for our chief engineer, Greg? Will we collect data that Wilma can use in her PhD thesis? Which of Felicity’s flight plans will these persistent low clouds allow? Will we even fly at all today?

These questions I ponder over a cheesy Vegemite scroll, and I ask Lenneke once again, ‘Think we'll fly today?'

'I told you, Chad, we'll find out at the weather briefing at noon.'

I reach for another Vegemite scroll and consider the lost opportunity that smoko represents. While I’m grateful for any officially sanctioned bonus meal, smoko serves as a daily disappointing reminder that there are no corresponding meals sandwiched between lunch and dinner, nor dinner and breakfast. During those hours we must cook for ourselves the mashed potatoes and curry found in the catch-n-kill refrigerator.

Noon comes and by quarter after, Lenneke returns from the operations office with a smile.

'We're flying today, you'll be on the flight, and you're going to Totten. Head to the skiway just after lunch.'

Totten Glacier was the subject of my PhD. It’s one of the largest glaciers in the world and I've spent countless late nights and weekends poring over satellite data and old ICECAP surveys of the area, but I've never never actually seen the beast with my own eyes. What will it be like? Will I recognize any features from all the satellite images that are burned in my brain, or will the scale and three-dimensionality of everything be so unfamiliar that I won’t know where I am without consulting the GPS? This flight will be where all those years of geophysical analysis and theory-based interpretation meet reality.

With 45 minutes to lunch and my survival bag already packed and sitting by the red shed door, there’s little to do but make myself a cappuccino and start planning the snacks I'll take with me on the plane. I've heard great things about Cheds, and I've heard that by popular demand the barbecue Shapes have gone back to their original recipe, but what if I find myself with a sweet tooth? Better take a sleeve of Tim Tams too, just in case.

After a satisfying meal of stir fry, salad, and sweet rolls, we take the yellow Hãgglunds up to the skiway and start preparing our instruments for the flight.

'Gravity meter on?'… ‘Check'.

'Data logger running?” … 'Check'.

'Radar ready?' … 'Check'.

'Snacks accessible?' … 'Check.'

In survival training we learned that food is the first layer of defense against the cold. ‘Baklava before balaclava,' they say. We are professionals. We take our training seriously.

Pilots Will and Aaron start the engines and we're off. Anticipation builds as we head toward Totten Glacier.

We fly over Law Dome, and it hardly seems like a dome at all without the vertical exaggeration I've grown accustomed to seeing in elevation profiles printed in the scientific literature. We begin to approach Totten and I think about the years I spent as a graduate student in Texas. There I’d sit in my windowless office, scouring every satellite image of Totten that has ever been taken, sorting through every photon from every laser that has ever been aimed at the ice here. It was my mission to fully characterize the undulations in Totten’s surface and generate topographic maps of the region at an unprecedented degree of accuracy and resolution.

As we fly, I see Totten in the distance and I begin taking notes in my scientific log book.

'13 Jan 2018, 4:18pm: Totten Gl. in sight. Appears white, generally nondescript.'

We reach the glacier and for almost half an hour we fly down its main trunk. I grow bored with the nearly featureless landscape and turn to my feedbag in hopes of finding something exciting, like chocolate biscuits or Mint Slices. But alas, just Spicy Fruit Rolls of disappointment. I may have to eat them, but I don’t have to like them.

Nearing the terminus of Totten Glacier, the topography around us begins to change. Massive ripples in the surface run perpendicular to the flow of ice, spanning the entire width of the glacier and stretching at least 10 or 20 kilometers on each side of the plane. I begin to recognize where we are as the glacier turns left and we follow its path. When we fly over a massive ice cliff that abuts smooth, flat sea ice, we know we've reached the end of the glacier and we're flying over the ocean. Captain Will calls over the headsets to let us know we're approaching our target.

Gonzo double checks the ropes that tether him to the plane and while we fly he begins turning levers to remove the airplane door. This WWII-era DC-3 was designed for paratroopers, and I begin to wonder what its makers would think if they knew that 75 years later it would here in Antarctica, deploying not men into combat, but scientific instruments into the ocean where no ship has ever sailed.

We spot an open lead in the sea ice and we know that’s our chance. Felicity prepares an expendable CTD sensor and hands it off to Gonzo. Approaching the lead, the countdown begins. Three, two, one, and with laser precision Gonzo pitches the CTD out the door and into a tiny sliver of open water. The CTD radios back, reporting the temperature and salinity of the seawater that flows beneath the vast floating ice shelf of Totten Glacier.

After a few more deployments we head back to Casey and arrive on station by midnight. We gorge on lasagna and roast potatoes. I finish with several slices of carrot cake and a nice pairing of re hydrated full cream milk. Next it’s off to begin the data download procedures which take all night. By morning, we're ready for another flight.

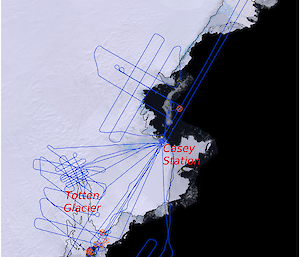

And so it went for 10 glorious days of flying this ICECAP season. We surveyed Totten Glacier, Denman Glacier, Moscow University Ice Shelf, Shackleton Ice Shelf, and the area surrounding Vincennes Bay.

We deployed 38 ocean sensors and flew more than 13,000 kilometers collecting data from ice-penetrating radar, laser altimeter, gravity meter, magnetometer, and optical imagery. It was a successful season thanks to endless support from operations and lots of hard work from the aviation ground support officers. Many thanks from the ICECAP team to the whole crew at Casey station!

ICECAP is supported by the Australian Antarctic Division, Antarctic Climate & Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre, and the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics.

By Chad Greene.