Science at Davis

Deep field Antarctic science, computer programming, radars and electronics are all in a day’s work for the science branch’s representative down here at Davis Station. Davis is the only Australian station to permanently provision a science branch expeditioner over winter and that’s with good reason; the systems and electronics collecting the valuable data is – in most cases – bespoke, specially designed for each respective task and require highly specialised knowledge to keep online and to operate safely.

Our role is unique amongst expeditioners as our handover takes most of the summer season and is particularly intense. We’re not only trying to adequately transfer knowledge about complex, bespoke systems but we’re simultaneously performing routine summer maintenance and interleaving the handover tasks with multiple deep-field activities in support of science objectives. Oh, and on top of that we have to remain vigilant and responsive to ad-hoc system outages to prevent the loss of valuable scientific data. When I first applied for this role I was working as a design engineer at a radar electronics research and development company and I was expecting my time down here to be dominated by managing ad-hoc electronics problems with circuit boards or devising special purpose solutions based on science’s needs. Although this is part of the job and I have spent some time under a microscope de-soldering and repairing troublesome circuit boards, I have actually spent most of my time coming to grips with the web of interconnected remote sensing and monitoring computers, preparing for deep-field activities or debugging data flow issues from a computer’s remote command line.

So what experiments are we running, what data are they collecting and why are we running them? As a passionate and outspoken advocate for climate science and as the incoming engineer I could write at length about each and every piece of equipment on station, but for the sake of this article I’ll keep the descriptions brief and colourful. Please know that the nuance of the atmospheric monitoring systems and the underlying physics, the sea-ice measurement techniques and the wildlife monitoring work could each fill multiple books or even their own libraries in their own right. With that caveat I suppose we could break down the systems into a few broad categories; atmospheric physics, wildlife monitoring, sea-ice monitoring and – for the sake of simplicity – other miscellaneous experiments.

Atmospheric physics has a long and proud history at Davis. So much so that there is dedicated infrastructure dating back to the early 1990s in the form of the Climate Process and Change (CPC) building (formerly the Atmospheric Science and Physics building) and the now retired lidar hut from the turn of the millennium, sitting proudly as the highest building on the station, like a quiet monument to past scientific endeavours. Among systems such as the all-sky cameras and aurora spectral cameras the CPC, as the atmospheric observatory, houses the long-term hydroxyl airglow measurement instruments which have been monitoring the bright infrared light emitted by the upper atmosphere, and indirectly the temperature of the upper atmosphere since the mid 1990s.

The other main atmospheric instruments that Davis expeditioners would be familiar with are the expansive array of different radar installations dotted along Dingle Road and appear to the uninitiated as a forest of masts and guywires.

The silent and unassuming antennas of the Medium Frequency Spaced Antenna (MFSA) array, for instance, send bursts of high-powered radio energy 100 km or more into the upper atmosphere and measures the fine ripples from the change of reflectivity in the atmosphere. Reflectivity that’s invisible to the naked eye, but appears to the radar like light appears to us, as it scatters on the ripples of a pond. It is with this sensitive instrument that we can measure atmospheric waves that have traversed the Earth’s surface several times, only to crash against the edge of space where they dissipate their energy like an ocean that’s crashing against a shoreline.

There’s also the installation affectionately called ‘the vineyard’ due to its neat rows of antennas strung in a formation that resembles rows of grapevines. The Davis climate of course is not conducive to cultivating grapes and these rows of antennae are in fact a doppler phased array VHF radar. This radar measures wind in the atmosphere from the near-surface up to about 15 km. The measurements from this array provides atmospheric physicists invaluable insight in to the behaviour of the boundary layer of the atmosphere and, as an added bonus, it is also available to the Bureau of Meteorology who ingest it into their prediction models.

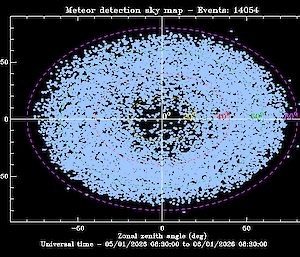

Now, last but not least, there are some unassuming antennas tucked away in a neat cross pattern behind the VHF radar vineyard. To best understand what these antennas are for, it is helpful to know that outer space isn’t as empty as we assume it to be. The Earth is hurtling through space and constantly colliding with tons of interplanetary dust. Each of the specs of dust that enter the atmosphere burn up in invisible high energy events, leaving a trail of ionised atmospheric gas. It turns out that these ionised trails provide excellent radar targets and these are what we’re watching for. These trails do dissipate rapidly, but while they persist, they move with the atmosphere and thus allow us to measure the wind at the edge of space. This meteor radar detects thousands or even tens of thousands of dust sized meteors careening through the upper atmosphere each day, giving us detailed wind information in the upper atmosphere. It is true that the meteor radar provides similar measurements to those taken by the MFSA, but by a separate mechanism, thus giving us improved confidence in the measurements from both the MFSA and the meteor radar.

I’ve focused on the radars up until now but there are so many other aspects to the work that’s performed by the electrical engineer here. As it’s the only role on station from the science branch we are the defacto custodian of all the science projects which – among many other things – includes the maintenance of the nest cameras. We conduct photo surveys of bird colonies during specific periods of the year and we maintain many other instruments for our international and academic partners.

An example of a non-atmospheric project which we supported recently is the upgrade, maintenance and retrieval of data from a remote geophysical satellite receiver monument, bolted to a football field sized patch of rock 370 km from Davis Station at a site called Carey-Nunatak. Before my time in Antarctica, and as an Australian, I had never encountered the term ‘nunatak’ which I now know is a mountain peak that protrudes from an ice sheet. The significance of the site from a geophysics perspective is that it provides a solid foundation to mount a GPS/GNSS receiver to, so that the movement of the continent can be accurately measured over time. From years of monitoring from stations such as this, geophysicists have observed that the Antarctic continent is rising as the ice on top of the continent decreases in mass. With the recent upgrade the recorder now has the capacity to transmit the data over a satellite link, rather than having to rely on the physical retrieval of the instrument.

My last example of some of the work that we’ve been doing is to talk about some of the nest camera maintenance and penguin colony surveys. The summer period and our access to helicopters has enabled the program to visit distant sites, perform arial surveys and service deep field nest cameras that have been inaccessible for many years. We’ve visited the Adele penguin colonies at the Svenner and Steinnes Island sites as well as the Amanda Bay emperor penguin colony. We’ve also managed to successfully photograph emperor penguin colonies at Cape Darnley and the West Ice Shelf. The Division has been operating nest cameras for many years and they’re managed at Davis by the engineer. There’s many scattered throughout the Vestfold Hills too, which monitor various colonies, but the local ones are far easier to access and I’ll be embarking on missions to service them throughout the winter when they’re accessible over the sea ice.

There’s a reason that the engineer handover occurs over the whole summer and I feel as though this article has barely scratched the surface of our work. As I wrap things up I’d like to thank James Newlands for his diligence over the past season, for his hard work and for his patience while teaching me over this summe. I wish him all the best for the next steps in his career and a smooth and safe transition back home.

Ross Gordon

Electronic Engineer

Davis Station

Coda: A Year and Change at Davis

At the time of writing it has been exactly 15 months since I boarded the RSV Nuyina with the 78th ANARE - bound for Davis and my duty as the new Electronics Engineer.

In that long stretch I have had some incredible experiences and forged lasting friendships. Slowly but surely I’ve been saying my goodbyes to Davis - my friends in the winter team, the freedom of the sea ice and those last trips hiking through the Vestfold Hills. In just one more month I myself will depart - a brief layover at Casey and then a whirlwind flight to Hobart. I find myself excited to return to friends and family and profoundly melancholy about leaving this place.

It has been a privilege to contribute to the scientific program and expeditioner community here at Davis. I will leave the atmospheric observatory and our many other scientific endeavours in the capable hands of Ross. I wish the 79th ANARE a fantastic remaining summer and winter!

James Newlands

Electronics Engineer

Davis Station