The study, led by Australian Antarctic Division marine ecologist Dr Jonny Stark, aimed to determine the composition, diversity and spatial variability of nematodes and copepods in shallow sediments at six sites around Casey station, and the effect of local environmental conditions, including pollution from historic waste sites.

At each of the six locations they found “surprisingly” distinct communities, dominated by nematodes but made up of different types (‘taxa’) of nematodes and copepods.

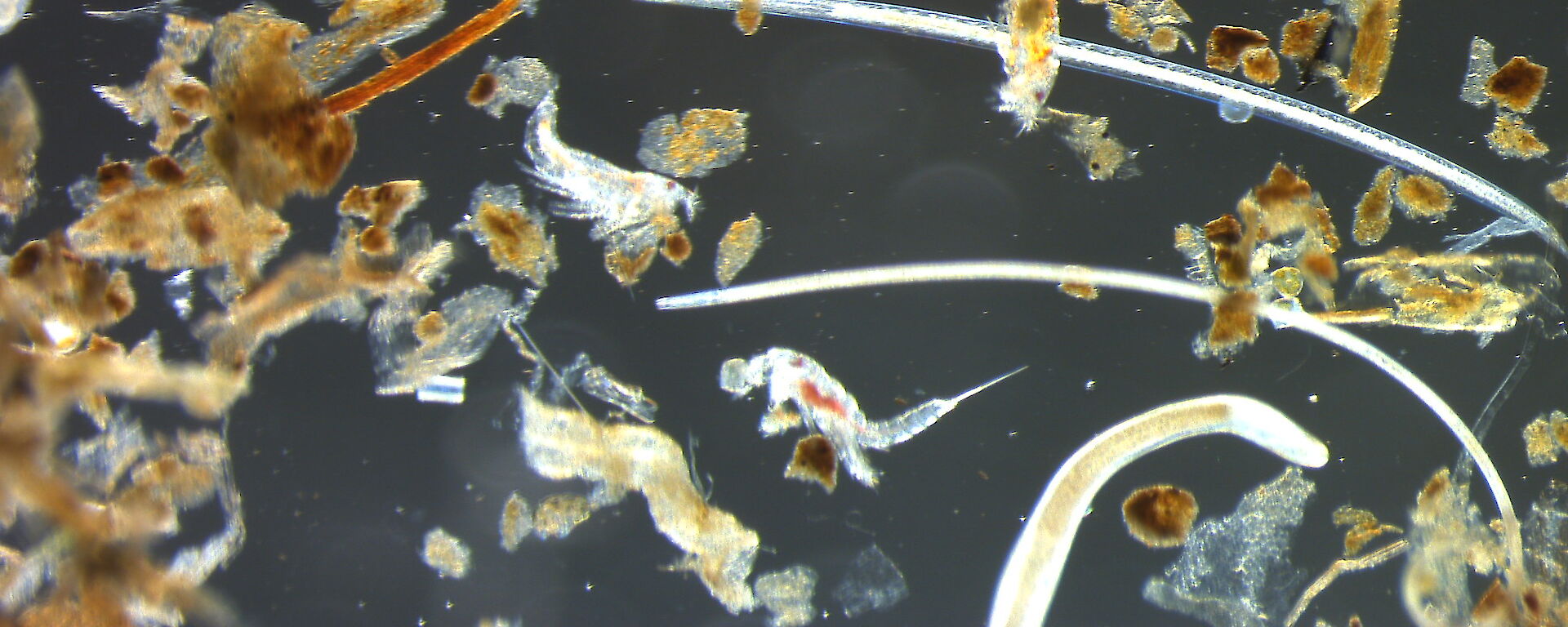

“Nematodes were the dominant group of small invertebrates observed at all locations, with 38 identified genera making up 95% of the meiofauna, and some 20 million individuals per square metre,” Dr Stark said.

“This dominance is thought to be due to nematodes’ ability to adapt and be resilient to varied environmental conditions.

“The next most abundant meiofauna group were copepods, with 20 families identified, in densities up to 900,000 per square metre.

“However all the locations had distinctly different communities, suggesting that unique conditions, and adaptation to those conditions at each site, have shaped the nematode and copepod communities over time.”

The study found that community diversity correlated strongly with metal pollution from historic waste disposal practices, and to a lesser extent the composition of sediments – including sediment grain size and organic matter content – as well as ocean conditions and physical disturbance from ice.

“The differences found between nematode and copepod communities were strongly correlated with higher concentrations of metals including lead, copper, iron and antimony,” Dr Stark said.

“Given the clear difference in both nematode and copepod communities at different locations, and their strong correlation with environmental patterns, particularly human disturbance, this study further supports the idea that these taxa may be excellent indicators of environmental change in Antarctic coastal waters.

The Australian Antarctic Program research, published in Frontiers in Marine Science in June, involved the Australian Antarctic Division, Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies and Florida State University.