Led by Australian Antarctic Division whale ecologist Dr Elanor Miller, the research modelled the presence of Antarctic blue whales in relation to the swarm characteristics of their main prey species, Antarctic krill.

The study marks the first time scientists have been able to measure schools of krill in the vicinity of Antarctic blue whales.

The modelling was based on data collected during a 42 day international research voyage to the Ross Sea, onboard New Zealand’s RV Tangaroa in 2015.

“We found that blue whales were close to krill swarms that were more than 15 metres high in the water column, less than 30 metres from the surface, and with more than 300 krill per cubic metre,” Dr Miller said.

“These finding support the theory that these extreme-size lunge feeders, target shallow, dense krill swarms to maximise their energy intake.”

The research used passive acoustic instruments, known as directional sonobuoys, to detect blue whale calls from more than 200km away, and then home in on the calls until the whales were sighted.

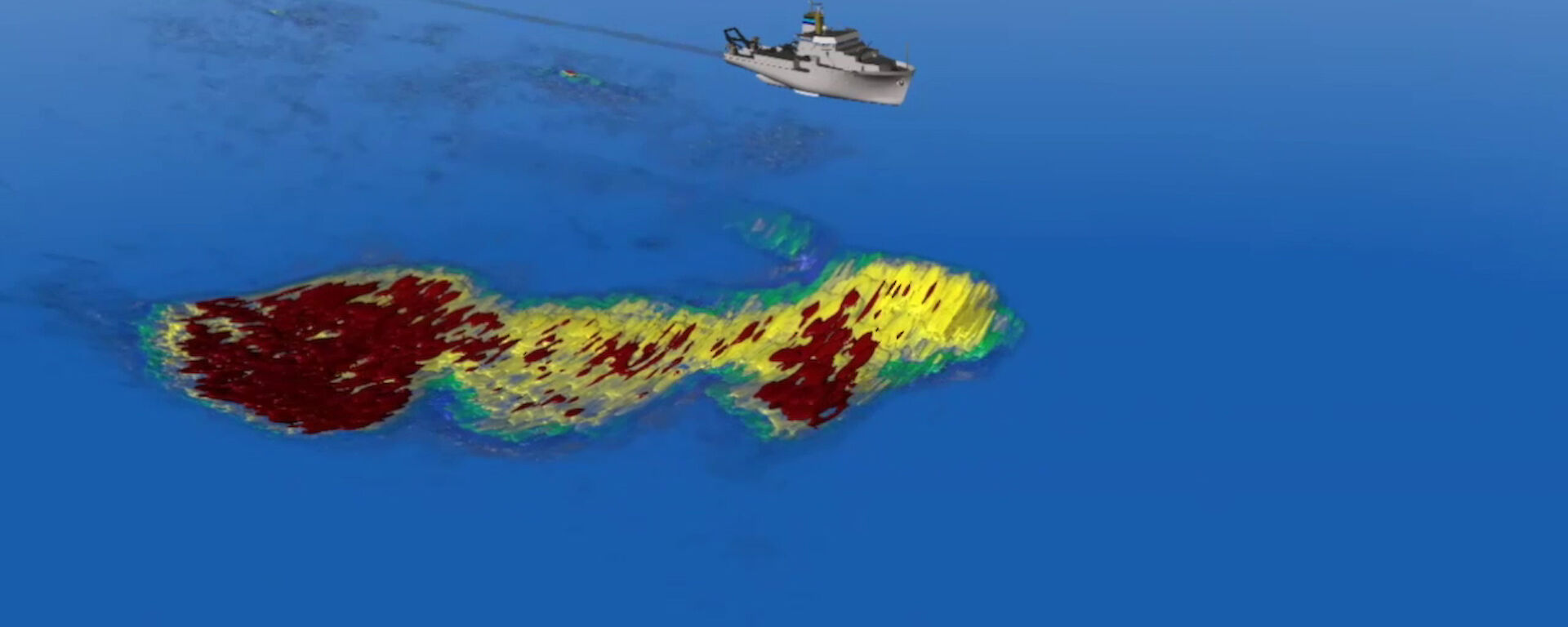

Active acoustics, using ‘echosounders’ on the ship, were then used to map krill swarms directly below the ship and within the whales’ vicinity.

“The echosounders send pings of sound into the environment and create an image of the returning echos bouncing off krill in the water column,” study co-author and whale acoustician Dr Brian Miller said.

“This allowed us to map the characteristics of krill swarms enroute to blue whale feeding grounds and compare them to swarms within the vicinity of blue whale aggregations.”

Krill distribution is highly variable in the Southern Ocean, ranging from large dispersed patches to dense and discrete swarms.

Swarms also stretch from tens to thousands of metres horizontally in the water column and tens of metres vertically.

These characteristics affect how easy krill are to detect, and whether they provide an energetically efficient meal for a predator.

“The swarms targeted by blue whales were neither widely nor evenly distributed throughout the study area, suggesting that the whales actively targeted them because it was energetically advantageous to do so,” Dr Elanor Miller said.

This searching for ‘ideal’ krill swarms and the patchiness of such swarms could explain why blue whales in Antarctica tend to aggregate.

Dr Miller said the research demonstrates that combining visual observations and recent advances in passive acoustic tracking methods, provides an effective way of studying the ecology of the rare and difficult to study Antarctic blue whale.

“As both Antarctic krill and blue whales play a key role in the Southern Ocean ecosystem understanding such predator-prey dynamics is important in the recovery of this critically endangered whale species and the future management of Antarctic krill fisheries,” she said.

The research was undertaken in collaboration with the International Whaling Commission’s Southern Ocean Research Partnership.