Stronger winds, increased warming, ocean acidification and declining sea ice have been identified as major threats to some of the keystone members of the Southern Ocean community — phytoplankton.

A recent Australian Antarctic Program review, published in Frontiers in Marine Science, predicts the likely impact of climate change on phytoplankton across various regions in the Southern Ocean.

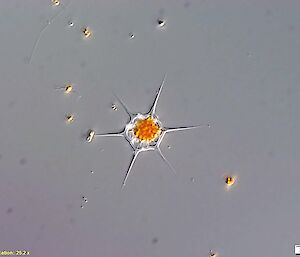

Phytoplankton are single celled marine plants at the base of the Antarctic food web, which sustain the immense diversity of life in Antarctica including krill, seals, penguins and whales.

Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies PhD student and review co-author, Stacy Deppeler, said the Southern Ocean comprises about 20 per cent of the world’s oceans, and contains a range of environments which will be affected differently by a changing climate.

“We will see changes in the growth, survival, productivity, composition and seasonal abundance of phytoplankton and this will in turn alter the quantity, quality and size of the phytoplankton,” Ms Deppeler said.

“Phytoplankton also play a critical role in mediating global climate by removing carbon dioxide from the air and releasing chemicals that foster cloud formation, so any slight changes for these small organisms will have a big impact.”

The review synthesises more than 350 published papers and examines five different regions, from the sub-Antarctic zone to the Antarctic continent.

Co-author and Australian Antarctic Division marine microbial ecologist Dr Andrew Davidson, said predicted changes across the regions include increased warming, higher visible and ultraviolet light and increased acidity.

There will also be changes in nutrient availability, reduced sea ice extent, thickness and duration, and increased melting of glaciers and icebergs.

“Many of these changes will tend to favour the small, flagellate phytoplankton over the larger diatoms,” Dr Davidson said.

Diatoms are mainly eaten by krill, which are then consumed by the larger Antarctic species such as penguins, seals and whales. Small phytoplankton are generally eaten by gelatinous grazers such as salps and smaller zooplankton like copepods.

“One phytoplankton species tipped to benefit from climate change is Phaeocystis sp., a small phytoplankton that forms gelatinous colonies and produces large amounts of sulfur compounds which promote cloud formation, subsequently influencing global climate.

“These changes will have a significant effect on the biogeochemical processes in the Southern Ocean.

“They will affect the ‘biological pump’ (the phytoplankton-mediated movement of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the deep ocean), the ‘microbial loop’ (the movement of carbon between marine microorganisms, by grazing and bacterial remineralisation), and nutrition for higher organisms,” Dr Davidson said.

Ms Deppeler said the effect of climate change on phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean is ultimately going to be determined by the timing, rate and magnitude of change in each stressor and the order in which they occur.

“The response of phytoplankton to future environmental conditions in the Southern Ocean will eventually depend on their capacity to adapt and evolve,” she said.

“We don’t know yet whether their ability to adapt will be outpaced by changes, but we do know that changes at the base of the food web will profoundly affect the chemistry of the ocean, higher organisms and climate change.”