Chemical clues absorbed from the atmosphere by Antarctic mosses during nuclear tests in the 1950s and 60s, have provided scientists with evidence of significant climate change in East Antarctica.

The discovery, reported in Global Change Biology, comes after researchers from the University of Wollongong (UOW) and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) found that the dramatic increase in atmospheric radiocarbon (14C), known as the ‘bomb spike’, was detectable in living moss shoots 50 years after nuclear testing, and could be used to track changes in moss growth rates.

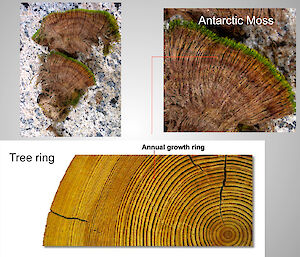

The research team, led by UOW Professor Sharon Robinson, collected samples of four moss species from five sites in East Antarctica and analysed them for their 14C content. Spikes of 14C detected in the samples were correlated with records of annual atmospheric 14C and 14C tree-ring data, which then allowed the team to calculate the age of the moss samples.

‘Mosses grow in an incremental fashion from the shoot tip and retain a record of atmospheric carbon encountered over their photosynthetic lifespan along the length of their shoots,’ Professor Robinson says.

‘In some of our moss species the peak of the radiocarbon bomb spike was found just 15mm from the top of the 50mm shoot, suggesting that these plants may be more than 100 years old.’

Having dated the moss stems the team found that growth rates varied over time and with location, between 0.2 and 3.5mm per year. They then used another chemical signal known as δ13C to track changes in water availability – which has a profound impact on moss growth.

‘Growth rates in the 1990s and early 2000s were lower than in 1980 for all four samples obtained from the Windmill Islands, whereas the two samples from the Vestfold Hills showed higher growth in the most recent decades,’ Professor Robinson says.

The researchers found that increasing wind speeds were correlated with reduced moss growth during the summer growing season, due to dehydration, while higher temperatures, which enhance ice melt, correlated with increased growth rates.

Research has shown that surface wind speeds have increased significantly over the world’s oceans in the past 20 years and around the Antarctic continent as a result of ozone depletion and increasing greenhouse gases. Increasing wind speeds have also been recorded in the Windmill Islands, where the sampled moss growth rates have declined. Areas where the sampled moss growth rates had increased had a wetter microclimate, as a result of shelter or proximity to lakes.

‘Our results point to a profound influence of recent climate change on the Antarctic flora, with δ13C profiles indicating the observed effects of temperature and wind speed are most likely due to the impact of these climate variables on water availability,’ Professor Robinson says.

Read more about this work in Global Change Biology: Clarke, L. J., Robinson, S. A., Hua, Q., Ayre, D. J. and Fink, D. (2011). Radiocarbon bomb spike reveals biological effects of Antarctic climate change. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365–2486.2011.02560.x

Professor Robinson’s research is part of the Australian Antarctic program.