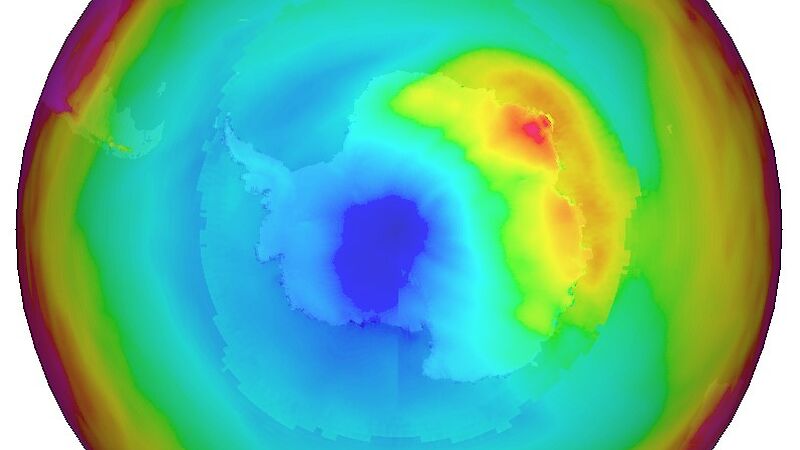

The ozone layer in Earth’s atmosphere absorbs harmful ultraviolet light from the Sun, but since the late 1970s, the ozone hole has increased the risk of sunburn for life in Antarctica.

Sunburn is a hazard that all Antarctic expeditioners need to protect against.

By monitoring and understanding changes in the ozone layer, we are better anticipating future climate, as well helping to protect the people of the Australian Antarctic Program.

Australian Antarctic Program atmospheric scientist, Dr Andrew Klekociuk, said that each year the annual opening of the ozone layer starts around August in Antarctica, peaks in September and then drops away by December.

“Climate variability causes the ozone hole to be a little bit different every year, but this year the unusual thing was the ozone hole opened early,” he said.

“This appears related to the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha‘apai volcano eruption last year, which shot water vapour into the stratosphere.”

The water vapour influenced the balance of chemical reactions in the ozone layer.