The recorded data will be the first of its type collected in the region at this time of the year and will be used to inform aspects of a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation for the Davis Aerodrome Project.

“This is the first time we’ve deployed acoustic moorings in such a challenging environment, through the sea ice, and there’s real potential to discover something new,” Dr Miller said.

“The key information we’re after is which species are present and for how long, so we can start to gather some baseline data on marine mammal activity in the region.”

Hydrophones within each mooring will record very low frequency sounds produced by baleen whales, mid-frequency sounds produced by toothed whales and seals, and super high frequency or ‘ultrasonic’ sounds – such as echolocation clicks used by dolphins.

“The species we’re most likely to hear are Weddell seals, which tend to inhabit shallower water near the coast, and breed in the vicinity of Davis research station,” Dr Miller said.

“A recent study found that Weddell seals make ultrasonic sounds, as well as their characteristic ‘other-worldly’ trills, so we should get some interesting recordings.”

Sound string

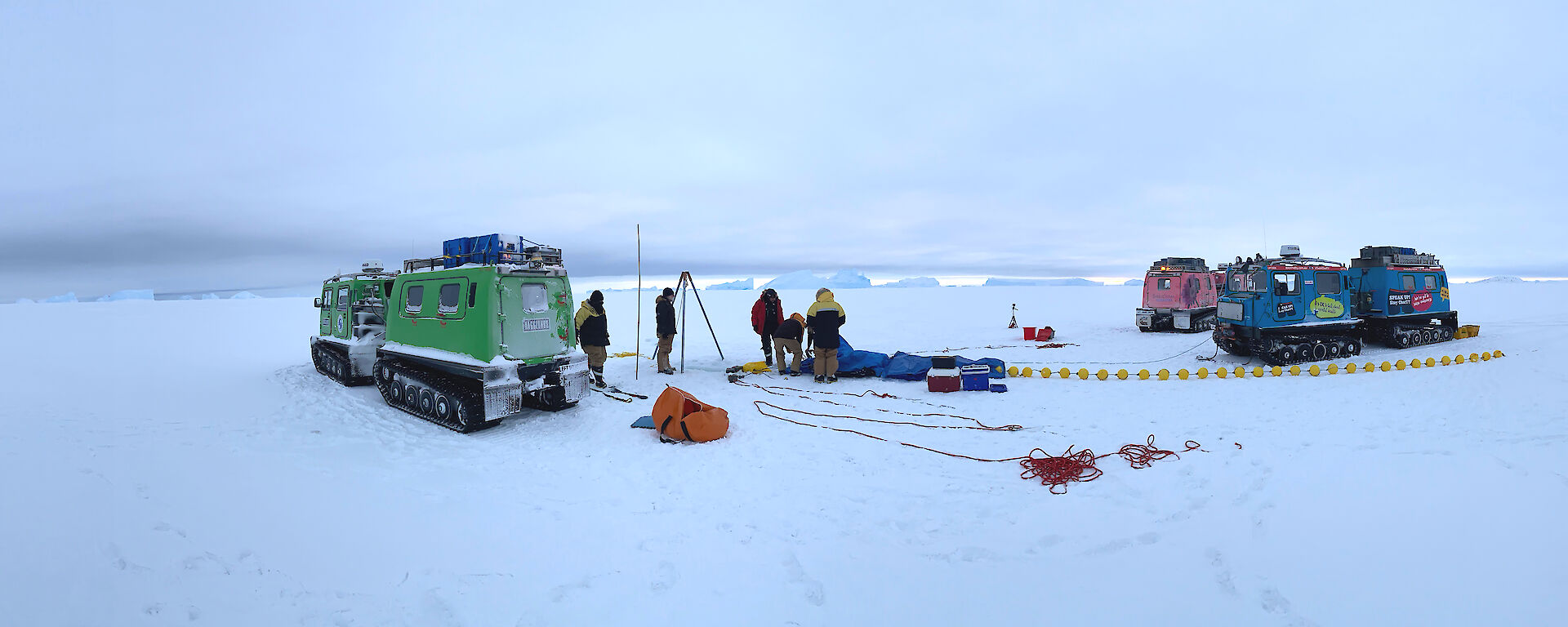

Environmental Officer, Helen Achurch, and a group of Davis station expeditioners, deployed the moorings in Long Fjord (near the site of the proposed runway) and near the shipping route into the station.

“The moorings are made up of a string of components,” Ms Achurch said.

“These include anchoring weights and an acoustic release – to decouple the anchor from the rest of the mooring during retrieval – a hydrophone, data storage, external battery pack and floats.

“Once lowered through a hole in the sea ice the moorings descend to the sea floor, between 50 and 250 metres below.

“The weights anchor the moorings in place, while the floats suspend the hydrophones off the bottom.”

Ice challenge

The moorings were designed to be carried by a small team to site, assembled, and then lowered through a 30 centimetre-wide hole in the ice, in locations suitable for recording the marine soundscape.

However deploying the 250 kilogram moorings through 1.3 metre-thick sea ice proved a challenge, as the team had to cut and drill the holes by hand and keep the instruments relatively warm.

“At each location we cut holes in the sea ice with a chainsaw and ice auger and then used our search and rescue training to set up some ice anchors to gently lower the moorings through the hole,” Ms Achurch said.

“As it was -20°C outside, we kept the moorings wrapped up in blankets and hot water bottles on insulated sleds, to ensure they didn’t get any colder than -5°C.

“Once the hole was ready we assembled all the components, turned the instrument on, and lowered it through the ice.”

The moorings will be retrieved in summer once the sea ice has cleared.

When the acoustic release is triggered the moorings will separate from their anchor and the float string will lift the units to the surface for collection.

“Acoustic moorings provide a really efficient way to detect a lot of animals that we might not be able to detect visually,” Dr Miller said.

“This is frontier science, and provided the instruments don’t get crushed by an iceberg, it will be really interesting to see what species they detect.”