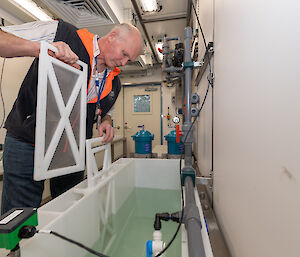

An Australian Antarctic Division team designed the aquaria, and mechanical plant needed to run them, to fit inside three 20-foot shipping containers that can be attached to Nuyina’s deck and plugged directly into the ship’s services.

Engineer Steve Whiteside said the aquaria can be configured to suit the research needs at sea, before they’re loaded onto the ship.

“We can install different sized or shaped tanks, or particular scientific equipment, in the weeks or months before a voyage, saving valuable time during the busy port call period,” Mr Whiteside said.

“Once on board, the aquaria are plugged directly into the ship’s power, water, air and alarm systems via a standard interface.

“When the ship returns from a voyage, the containers can simply be craned off the ship onto a truck, transported to the Australian Antarctic Division, and then plugged into our land-based services while we unload our precious specimens into a more permanent home.”

Mr Whiteside and his team worked with krill biologist Rob King to ensure the design worked from both an engineering and scientific perspective.

Mr King drew on his 25 years of knowledge working in the krill aquarium on board RSV Aurora Australis and at the Australian Antarctic Division’s land-based aquarium.

The end result is a system that can control the temperature of seawater no matter the location of the vessel, and maintain two aquaria containers at different temperatures, anywhere from −1.5°C to 15°C.

“We will have millions of litres of clean seawater available to us to keep our animals healthy, but it won’t always be at the right temperature, so we’ve had to design an efficient temperature exchange system,” Mr King said.

“On our way south we might catch some organisms in temperate or sub-Antarctic waters, and we’ll be able to maintain them at that water temperature for the whole voyage. We can also hold animals collected in colder Antarctic waters in separate tanks, for the voyage home.”

A critical part of the success of the system is the mechanical plant, which includes a chiller and associated coolant reservoir, water pumps, heat exchangers for manipulating water temperatures, and an automated control system.

But scientists won’t know for sure whether the system is reliable and safe for Antarctic organisms until they test it at sea.

“Contamination is a big issue for aquaria, and everything that has contact with sea water has to be built from inert materials, such as titanium and silicone, so that poisonous metals or chemicals don’t leach into the water and kill our organisms,” Mr King said.

“While we know that our aquaria have been designed with this in mind, we don’t know for sure how they will interact with the ship’s systems.

“It could be as simple as a bit of the wrong type of weld material in a connecting pipe, and we’ll have to find it and correct it.”

The containerised aquaria will improve the survival rate of krill and other organisms during their transfer from ship to shore – where they’ll be used in experiments on krill behaviour, physiology and response to climate change.

Previously, organisms were hand-netted from tanks in the Aurora Australis’s cold room and transferred in 10 litre buckets, packed in ice, to the Antarctic Division’s land-based aquarium; a slow, labour-intensive process that reduced the number and quality of precious live specimens.

The aquaria are part of a larger suite of ‘containerised laboratories’ that includes general and temperature controlled laboratories, designed specifically for RSV Nuyina.

The aquaria and laboratories were constructed by Tasmanian company Taylor Brothers, while the AAD instrument workshop constructed the internal aquarium systems.