The research, published in PLOS ONE today, will allow environmental managers and industry to assess what impacts human activities might have on these gigantic animals during their more than 10,000 km round-trip migration.

Australian Antarctic Division marine mammal scientist and lead author of the research, Dr Mike Double, said the published migratory movements could be used in a precautionary way, to identify and manage risks within the pygmy blue whale migratory range, such as vessel traffic, oil and gas field locations and increased ambient noise from development, shipping and fishing.

“This is particularly important, as pygmy blue whales were targeted by commercial and illegal whalers prior to the moratorium on whaling, and we don’t know if the population has recovered subsequently,” Dr Double said.

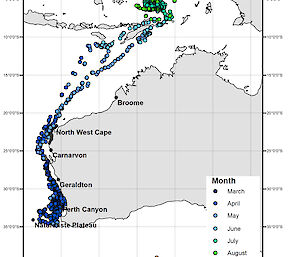

Eleven pygmy blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda – a subspecies of blue whale) were tagged in April 2009 and March 2011 within the Perth Canyon off the coast of Western Australia. The tags transmitted to the Argos satellite system from between eight and 308 days. All the whales travelled north after tagging, except one, which remained in the tagging location for eight days, before its tag failed. Throughout the tracking period, each whale covered some 3,000 km, moving at about 22 km per day (see video below).

Australian Antarctic Division scientist and co-author of the research, Dr Virginia Andrews-Goff, said the tagged whales travelled within about 100 km of the west Australian coastline throughout March and April, until they reached the North West Cape peninsula, about 1,200 km from the Perth Canyon.

“They continued to travel north during May, about 240 km offshore, and by June they were travelling through the Savu and Timor seas,” Dr Andrews-Goff said.

“They stopped within the Banda and Molucca seas, just south of the equator, and remained there until September. This timing suggests these seas are important feeding and calving grounds for this subspecies.”

One tag continued to transmit intermittent location information in December and February, by which time the whale had migrated to a region south of the Great Australian Bight.

“These 11 satellite tracks line up closely with blue whale positional information collected by researchers both pre- and post-whaling, through sightings, strandings, acoustic recordings and mark-recapture,” Dr Andrews-Goff said.

However the research team said acoustic calls had also been recorded well to the west of the tracked migratory route, within subantarctic waters and potentially Antarctic waters, indicating multiple migration routes or ‘elasticity’ in migratory behaviour. This behaviour may be related to changes in prey availability.

Research collaborator Curt Jenner, Managing Director of the Centre for Whale Research in Western Australia, said the study highlights the need for ongoing conservation and management efforts in both Australian and Indonesian waters.

“When migratory animals routinely cross international borders, international cooperation is needed to implement conservation strategies that use information on habitat use and movement patterns,” he said.

“A combined approach by industry and managers when accounting for the movements of the pygmy blue whale utilising Australian and Indonesian waters will allow the recovery of this previously exploited species.”

*Pygmy blue whales reach about 24 m in length and are slightly smaller than their Antarctic blue whale cousins, which grow to about 31 m in length.