Tag - you're it!

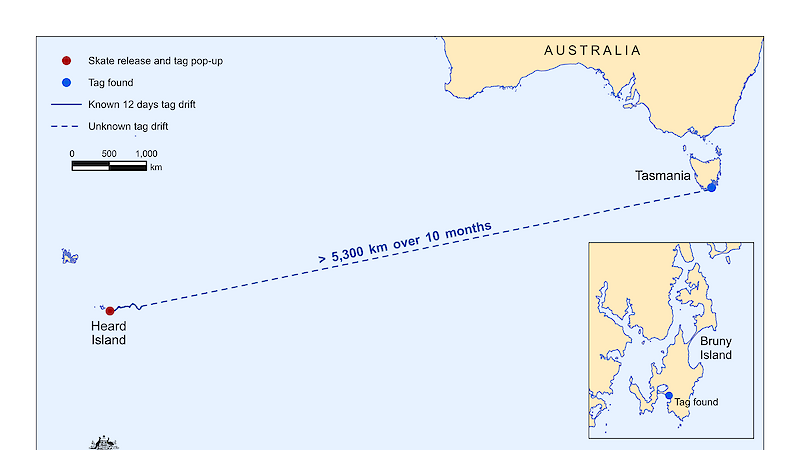

What Dr Jaffrey found was one of 45 pop-up satellite tags deployed on Kerguelen sandpaper skates and Patagonian toothfish by Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) PhD student, Colette Appert, and former Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) fisheries scientist Dr Jaimie Cleeland (now at British Antarctic Survey).

The pair spent 97 days on board the Patagonian toothfish longline-trawling vessel, Cape Arkona, last year, as part of an AAD science-industry collaboration supporting the sustainable fishery around Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI).

Dr Appert’s research aims to understand the survival rates of sandpaper skates after release from being caught on fishing lines.

These deep-sea denizens are only found around Heard Island, in waters down to 2,000 metres. They are the most abundant bycatch species in the HIMI toothfish fishery, and fishers are required to release all healthy skates.

Observers from the Australian Fisheries Management Authority are also present on all vessels fishing at HIMI, and record all catches and releases of skates.

To find out how many survive, Dr Appert assessed captured skates for injuries, and then took blood samples to look for stress markers that might reveal the likelihood of survival.

She also tagged 24 skates with pop-up satellite tags, to investigate activity patterns once the animals were returned to the ocean.

The tags detach and surface after 30 days, to transmit a portion of their data to satellites.

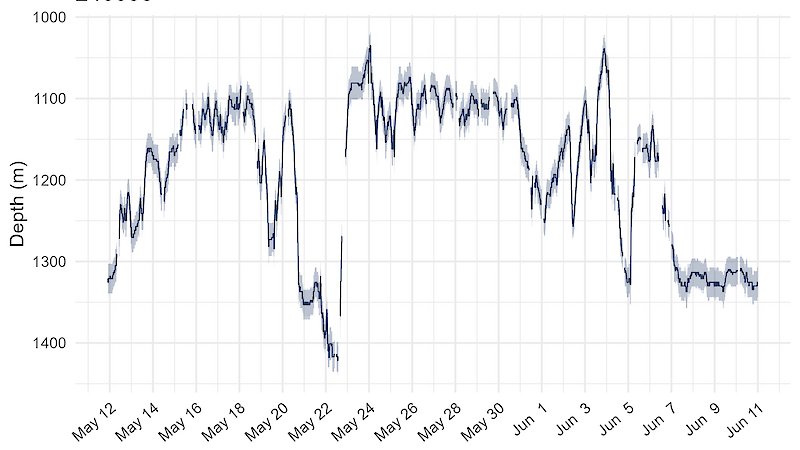

“We program the tags to transmit depth, activity and temperature, and a summary of this data is transmitted to the satellite,” Dr Appert said.

“But there is a lot of raw data on the tag that we can only access if we recover it – and it’s a miracle if that happens.

“The discovery of this tag will allow me to dive into the complete and extremely high resolution data for this skate, and I can’t wait.”