“At Macquarie Island we have a radionuclide station that monitors radioactive content in the air and if we detect noble gases, that would be indicative of a potential nuclear test,” CTBTO radionuclide project manager Nikolaus Hermanspahn said.

“Air is sucked in through a vent and a filter collects all the dust. Then the local operator (usually the station’s Comms Tech officer) takes the filter out and compresses it into a little disc.

“It’s stored for 24 hours and then the particles are counted on a spectrometer to determine the radioactivity content.”

That information is transmitted to the CTBTO's International Data Centre in Vienna for analysis and distributed to all state parties.

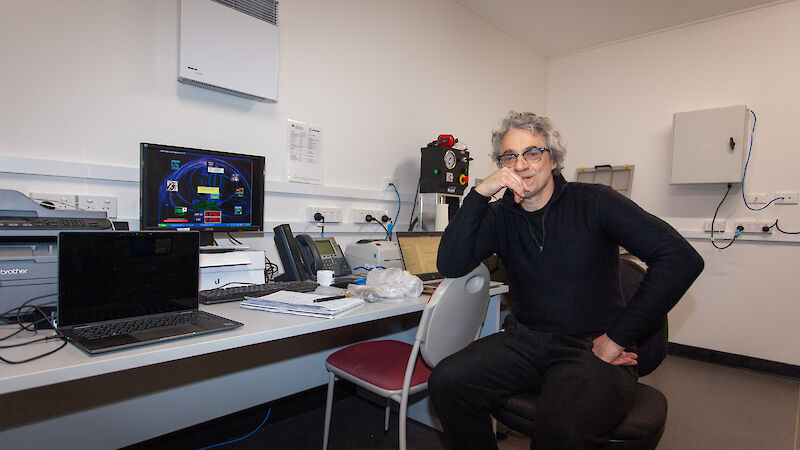

Mr Hermanspahn travelled to Macquarie Island on RSV Nuyina’s resupply voyage in May, with colleagues from the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA).

The group spent several days on the island, checking that the monitoring equipment was properly calibrated and working efficiently.

“Macquarie Island is important because we need as much geographical coverage as possible and these big ocean areas are a real challenge,” Mr Hermanspahn said.

“The fact that Macquarie Island is staffed year-round is critical for our operations there. Without the research station we wouldn’t be able to run the monitoring station and that would be a big hole in our network.”