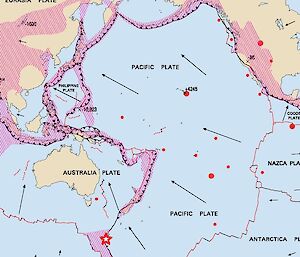

The array of 32 seismometers, deployed across the tectonically active area known as the Macquarie Ridge Complex (MRC), are part of a project led by the Australian National University (ANU)* – with help from Australian Antarctic Program expeditioners - to study the mechanisms causing submarine earthquakes in the region.

Earthquake hotspot

ANU Head of Geophysics, Professor Hrvoje Tkalčić, said the MRC has experienced two major submarine earthquakes in the past 32 years, of magnitude 8.2 in 1989 and 8.1 in 2004, both caused by predominantly ‘strike-slip’ events – where horizontal rock masses slip past each other parallel to the fracture or ‘strike’ between them.

The violent earthquakes shook Macquarie Island research station, and tremors were felt as far away as Tasmania and the South Island of New Zealand.

“This strike-slip mechanism baffled the global seismological community, as strike-slips of this magnitude usually only occur in thick continental crust, not thin oceanic crust,” Professor Tkalčić said.

“As the MRC sits on the boundary between the Pacific and Indo-Australian plates, it’s possible we’re witnessing the formation of a new ‘subduction zone’, where the plates collide and one slides beneath the other.

“This project aims to collect data that will help us better understand the mechanism of earthquakes in the region, and generate maps of the subsurface architecture.

“The maps will help us predict how seismic energy from hypothetical future earthquakes spreads, and to simulate different scenarios of wave propagation, for earthquakes and tsunamis.”

Deep-sea sensors

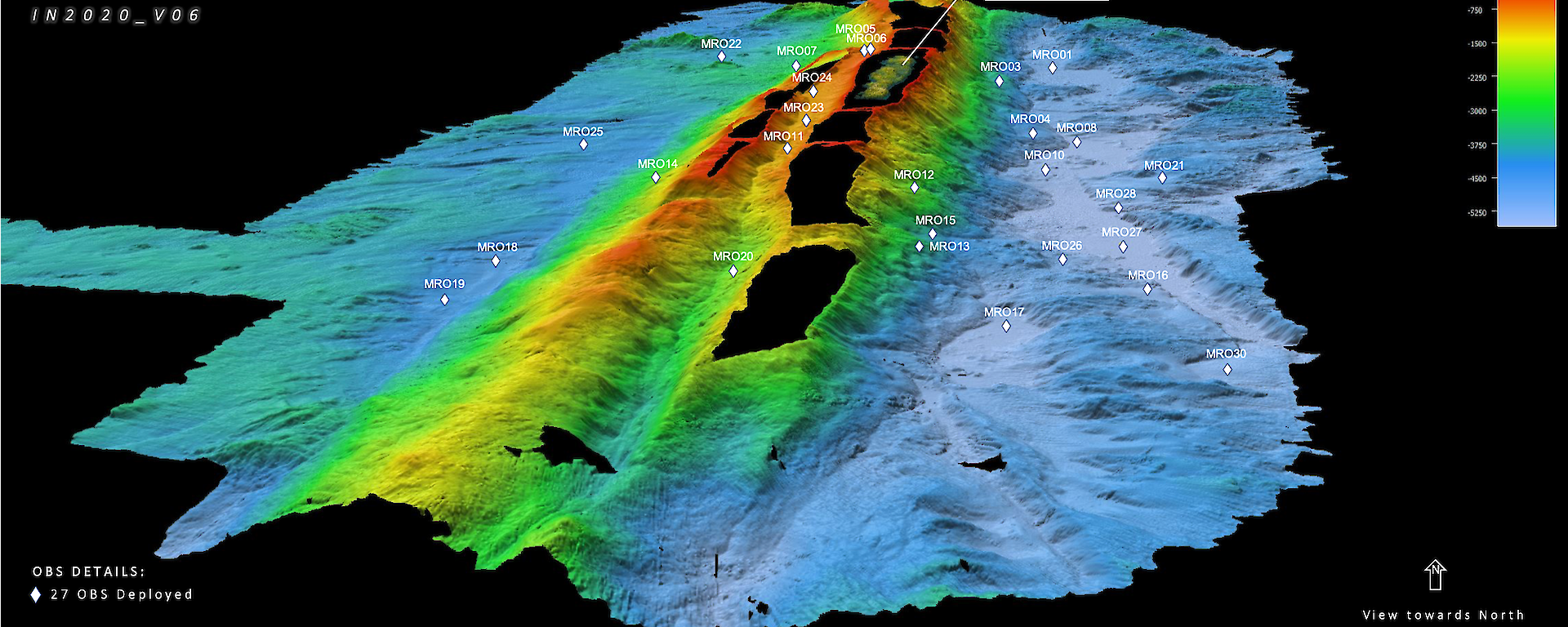

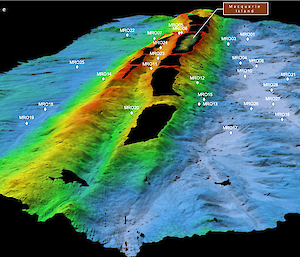

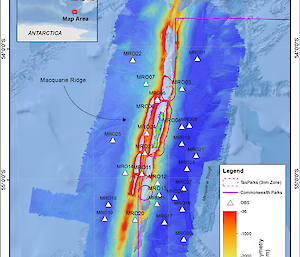

In late 2020 Professor Tkalčić and colleagues from ANU and the University of Tasmania, on board CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator, deployed 27 ocean bottom seismometers on the sea floor around Macquarie Island, covering some 25,000 square kilometres (described in this EOS article).

The seismometers measure ground movement caused by earthquakes locally, regionally, and more than 1000 kilometres away (‘teleseismic’ distances), as well as seismic and ambient noise.

The team deployed the instruments in ‘smooth spots’ amongst the extraordinarily steep, rocky and hazardous submarine terrain, at depths of between 520 and 5517 metres, and in particular patterns.

“The southern part of the seismometer array has three spiral arms, while the northern part has an X shape,” Professor Tkalčić said.

“This configuration is designed to achieve the best possible amplification of the signals from distant earthquakes, in the same way an antenna or a telescope works.”

Walking the shaky line

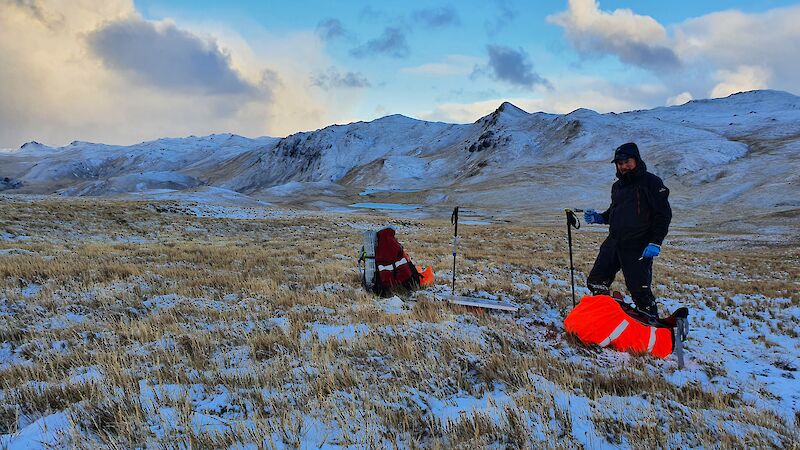

In June this year the final components of the array – five land-based seismometers – were installed on Macquarie Island by Australian Antarctic Program expeditioners.

“The seismometers are evenly spaced along the main axis of the island to study crustal and upper mantle structure beneath the island, in conjunction with the ocean bottom instruments, Professor Tkalčić said.

Macquarie Island station doctor, Rob Dickson, and a small team of volunteers, traversed the island’s main walking track to install the gear.

“We carried about 25 kilograms of gear as well as all our personal field and safety gear,” Dr Dickson said.

“Most people on station helped in some way, including the tradies – with their shovel tickets, our communications technician, and the Tasmania Parks rangers who spearheaded the southern installations, as they are down that way regularly.

“The Station Leader and I also consider carrying a heavy back-pack for the sake of it to be ‘recreational activity’.”

Once at an installation site the group dug a 50 centimetre-deep hole, connected the seismometer, battery and solar panel to a regulator, protected the seismometer with plastic bags and covered it with dirt, staked down the solar panel against the wind, and synced the instrument through Bluetooth to a tablet.

“We also put black electrical tape on any red cords, as skuas can mistake red wires for delicious intestines,” Dr Dickson said.

Solving tectonic puzzles

The ocean seismometers will be retrieved in November 2021 and the land-based instruments after at least a year of deployment.

While the thought of living on a shaky isle might deter some, the team at Macquarie Island research station is well prepared for any damage caused by a quake or resulting tsunami, with a shelter 100 metres above the station on Wireless Hill.

The shelter contains communications equipment, clothing and food, to sustain the group until help – via ship or airdrop – arrives.

Professor Tkalčić said the insights gained into the physical mechanism generating submarine earthquakes in the region will help scientists better understand the risks.

“This knowledge should allow us to provide more accurate assessments of earthquake and tsunami potential in the region, which we hope will benefit at-risk communities along Pacific and Indian Ocean coastlines,” he said.

“This work could also be crucial to helping us answer one of the biggest scientific puzzles in plate tectonics – how subduction begins.”

*The research is led by the Australian National University, partnering with Geoscience Australia, University of Tasmania, California Institute of Technology and Cambridge University. It is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.