World Migratory Bird Day

While South Polar Skuas do like to eat penguin chicks, they’re often unfairly pigeon-holed as thuggish baby-eating bullies.

These tenacious birds are actually talented survivors that venture where others dare not go, with some of the longest migration routes on record.

New Australian Antarctic Division research aims to reveal more about the winter destinations of these long-distance travellers and their important ecological role.

To do this, seabird biologists Kimberley Kliska and Marcus Salton spent part of the 2019/20 summer near Mawson research station attaching 18 geolocator devices to small leg bands on the birds.

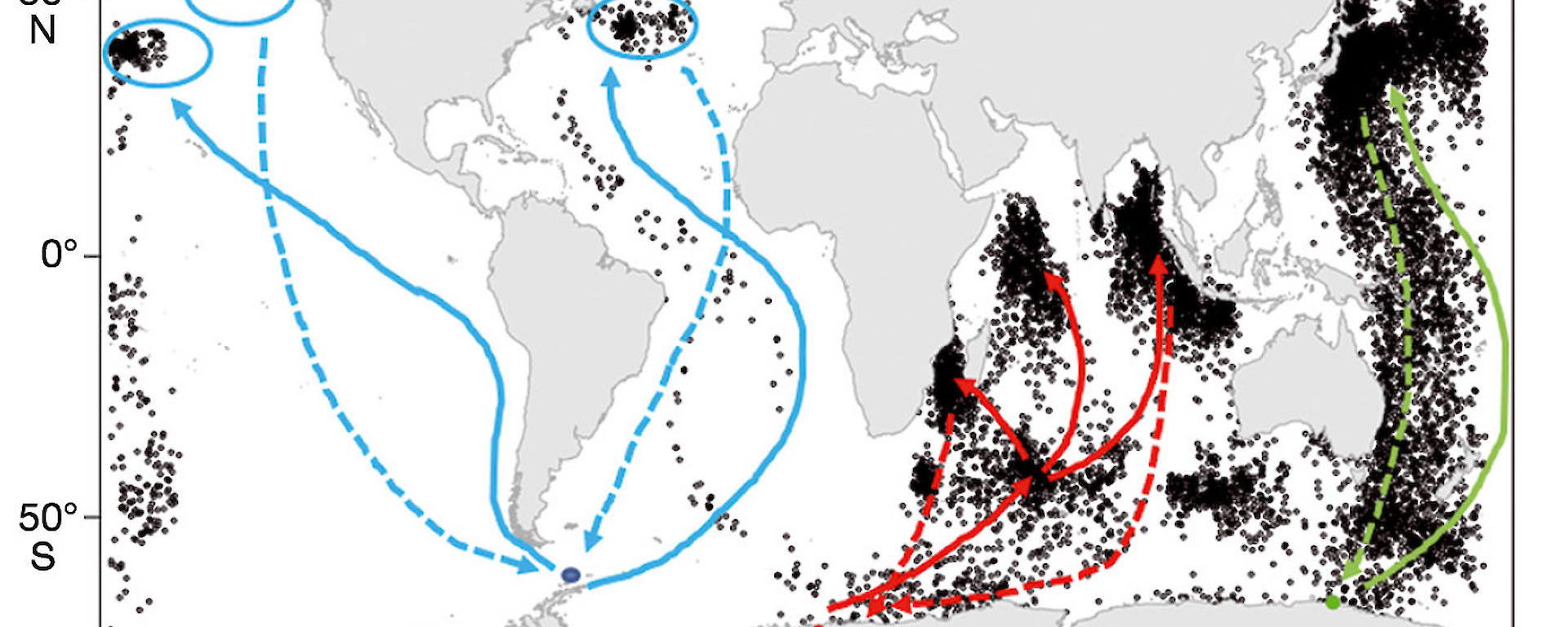

The migration routes of the gull-like South Polar Skuas (Catharacta maccormicki) are amongst the longest for any bird, with annual journeys of more than 10,000 kilometres between their feeding and breeding grounds.

“They’ve been tracked migrating between Polar regions, from Antarctica all the way to Greenland and Northern Alaska,” said Mr Salton.

Globe-trotting frequent fliers

During the Antarctic winter, South Polar Skuas fly giant figures-of-eight to the northern hemisphere and back, using prevailing oceanic winds to their advantage.

As a migratory species, they’re listed under an international agreement to which Australia is a party, and protected under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Historically the birds have been tracked by research based at the Antarctic Peninsula and other countries’ stations around Antarctica.

Banding studies were undertaken at the United States’ Wilkes station in the 1950s.

However, adult skuas from the eastern coast of the Australian Antarctic Territory have not been tracked before.

“We think adult skuas from east Antarctica migrate to the northern hemisphere each winter, but we don’t know for sure,” Mr Salton said.

“For the first time, we’re going to find out.”

The tiny geolocator loggers attached to bands on the legs of migrating skuas record times of sunrise and sunset, enabling the calculation of latitude and longitude.

They also record periods of saltwater immersion, allowing the estimation of time spent in flight or sitting on the water.

“Later this year we intend to retrieve the devices to download the data and fill in the gaps on the map, to complete the picture of skua migration,” Mr Salton added.

Eco-influencers

South Polar Skuas are a common sight in coastal Antarctica, especially near penguin colonies.

Large and long-lived, they’re ecologically important as top predators that exert a selective force on the evolution of other seabirds.

“They influence seabird populations by predating on eggs, chicks and adults,” Ms Kliska said.

“They also influence seabird behaviour by being an ever-present threat during breeding. Parents and their young learn to evade detection and capture, so only the alert and strong survive into the future.”

Skuas are well equipped for predation, with impressive webbed talons where the third claw faces backwards for a secure grip, and they can fly at speeds of up to 72 kmh.

Depending on the time of year, South Polar Skuas are resourceful scavengers as well as predators, targeting penguin colonies, petrels, fish, molluscs and crustaceans.

“In Antarctica, they have an important ecosystem function as ‘cleaners’, consuming a range of carrion from seal placentas to dead seabirds, helping to control disease,” she said.

“They’ve even been seen regurgitating an entire seal flipper!”

However, apart from personal observations, little is known about their local foraging behaviour within the Australian Antarctic Territory.

“This summer we also used GPS devices to investigate where skuas went looking for food while breeding — watch this space!” said Ms Kliska.

Talent for survival

Individual South Polar Skuas are recorded as far inland as the South Pole, further south than any other bird.

Resighting studies have shown the birds have a lifespan of 30 to 40 years.

They form strong partner bonds and tend to mate for life, which means they can avoid spending valuable time on courtship rituals during short breeding seasons.

While they will ‘divorce’ if a ‘better option’ presents itself, divorce rates are as low as 6.4 percent.

Fiercely territorial, they will defend a territory of up to two hectares in size by vocalising loudly, displaying their chest and wing size, and even dive-bombing each other.

Leader of the seabird ecology team at the AAD, Dr Louise Emmerson, said their research is also using genetic techniques to understand how related populations of skuas are to each other, and whether their population changes mirror the long-term changes of other seabirds and the climate.

“Studying the South Polar Skua allows us to develop a better sense of the inter-dependencies between species,” Dr Emmerson said.

“This is important in the short food chain of the Southern Ocean that is primarily driven by krill availability.”

The research is part of the AAD’s long-term seabird monitoring program, which has been informing the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and its regulation of krill fisheries for the last thirty years.

The remarkable migrations of South Polar Skuas bring a global dimension as well.

“Given the winter foraging range of South Polar Skuas is so broad, we’re also trying to understand their levels of contamination of mercury and persistent organic pollutants, as they may intercept a greater load of contaminants during their travels further north,” said Dr Emmerson.

Mark Horstman, AAD Media