Antarctic scientists have acquired the first detailed information about the reproductive maturity of Patagonian toothfish in the Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI) fishery, including the location and timing of spawning.

The research will improve the accuracy of stock assessment models that contribute to the setting of sustainable catch limits for the toothfish fishery, and will inform future harvest strategies that account for the movement of toothfish at different life stages, in the region.

Australian Antarctic Division fisheries scientist, Dr Dirk Welsford, said that for most of the Patagonian toothfish fishery’s 15 year history, very few spawning toothfish had been recorded. But in 2009 a number of spawning toothfish were captured during prospective longline fishing on the deep slope (at about 1700m) to the west of HIMI.

‘The Fisheries Research and Development Corporation and industry helped fund a systematic survey of the area in the winter of 2011 and we sampled over 11 000 fish,’ Dr Welsford says.

‘For the first time we were able to collect and study male and female toothfish at all stages of reproductive development, which allowed us to better define the size and age at which the fish mature and to produce a map of where they spawn and how deep they spawn.’

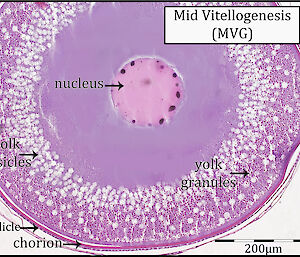

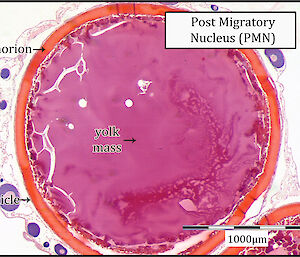

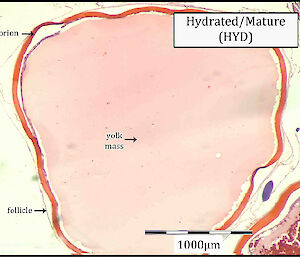

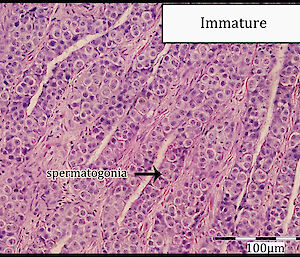

To do this the research team analysed thin sections of the ovaries and testes from the captured fish under the microscope, and matched sexual maturity to fish size, age estimates, and catch location.

Their analysis showed that the majority of female Patagonian toothfish begin spawning by about the age of 10, while most male fish reach reproductive age at about seven.

Before female toothfish spawn, the eggs in their ovaries go through 10 distinct stages of development. This includes a ‘yolk provisioning’ phase and a final hydration of the eggs, which visibly distends the abdomen of the fish, before they are released into the water column. Sperm go through three developmental phases before they too are released into the water column.

Microscopy also revealed that a substantial proportion of the mature female population may not spawn every year, possibly due to the relatively high cost of provisioning large quantities of large, yolky eggs.

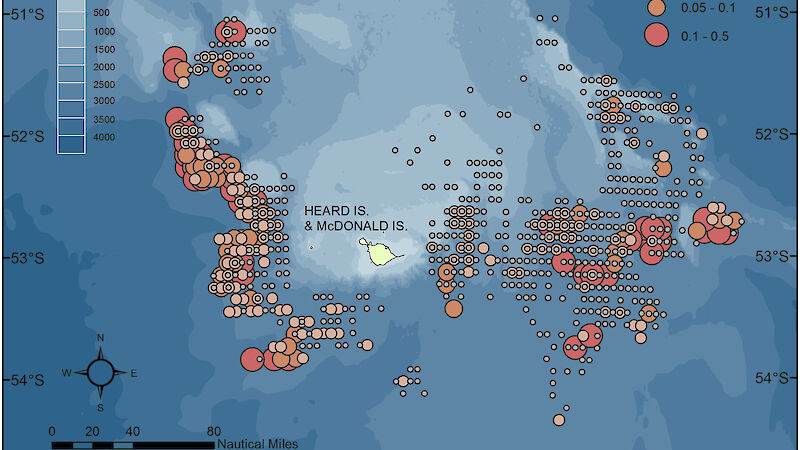

Matching maturity to catch location showed that the toothfish spawn predominantly on the slopes of the Kerguelen plateau (see map) to the northwest, west and south of HIMI at 1500–1900m depth in the late autumn to winter months (May-August). Juvenile fish are usually restricted to waters less than 1000m, while larger adult fish are encountered at depths of up to 2700m.

‘These findings are important in terms of assessing the growth, death and reproductive output of toothfish and the major locations used by spawning fish, to ensure fishing doesn’t cause an unsustainable impact,’ Dr Welsford says.

‘However, now that we know that spawning activity is widespread, and the HIMI longline fleet is relatively small and fishing effort is dispersed, it is unlikely that the fleet will substantially disrupt reproductive activity.’

The research will inform a new collaborative project being developed between the Australian Antarctic Division, the University of Tasmania and the Museum Nationale d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. The project will develop models and sustainable harvest strategies that account for the spawning locations, the movement of juvenile fish to spawning areas, and the differences in growth and maturation rates between male and female toothfish across both the Australian and French Exclusive Economic Zones on the Kerguelen Plateau. This work will in turn inform HIMI fishery management decisions made by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR).

‘The harvest strategies in fisheries managed by CCAMLR ensure that enough spawning stock remain to maintain ecological relationships and the natural levels of recruitment of young fish to the population,’ Dr Welsford says.

‘CCAMLR has agreed to our recommendation that the new information we’ve collected about age, growth and size at maturity, is incorporated into models for future stock assessments.’

The HIMI toothfish fishery is one of very few fisheries that have data on key population parameters such as size-at-age, catch-at-age, natural mortality and age-at-maturity. Dr Welsford says this standing is critical for ensuring organisations such as CCAMLR and the Marine Stewardship Council (see below) continue to recognise Australia’s sustainable management of this fishery.

Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division

Australian-caught toothfish a ‘best choice’ for consumers

Australian-caught Patagonian toothfish was labelled ‘best choice’ by the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch program in April, less than a year after the fisheries’ independent certification as sustainable and well managed by the Marine Stewardship Council.

The Monterey Bay Aquarium (MBAQ) provides ‘ocean friendly’ purchasing advice to consumers on over 2400 fisheries around the world and is widely respected for the high quality and independence of its work.

Australia has two fisheries for Patagonian toothfish (also known as Chilean Seabass) — the Macquarie Island Toothfish Fishery and the Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI) Fishery. Both fisheries were accredited as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council last year, after years of scientific research and the adoption of conservation and management measures in the region, through the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR).

The Patagonian toothfish fishery was once plagued by illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing. However, a collaborative effort by industry, government and conservation groups has seen illegal fishing of toothfish decline significantly and no illegal fishing vessels have been sighted in the Australian Fishing Zone since January 2004.

‘Now, the MBAQ has reviewed all the available information relating to the collaborative research and management efforts of the Australian Antarctic Division, the HIMI fishery, CCAMLR, and the Australian Fisheries Management Authority, and this best choice label reflects those efforts', Australian Antarctic Division fisheries scientist, Dr Dirk Welsford, says.