The scarcity of Antarctic blue whale sightings may be a thing of the past, thanks to acoustic technology that locates and tracks the leviathans from their songs.

By using sound rather than sight to find the whales, an Australian-led team of researchers got close to some 80 Antarctic blue whales during a seven week voyage to the Southern Ocean between February and March this year.

The 18-strong team of cetacean biologists, acousticians and observers, onboard the New Zealand trawler Amaltal Explorer, made 57 photo-identifications of the animals, obtained 23 skin samples for genetic analysis and attached satellite tags to two.

The research aims to estimate the abundance, distribution and behaviour of this rare and iconic species and gain insights into their behaviour. The work is part of the Southern Ocean Research Partnership — a collaborative consortium for non-lethal whale research involving ten countries*.

Lead acoustician, Dr Brian Miller, from the Australian Antarctic Division, said the acoustic technology used on the voyage — previously used by the military to detect submarines — could revolutionise the way scientists work with blue whales in the future.

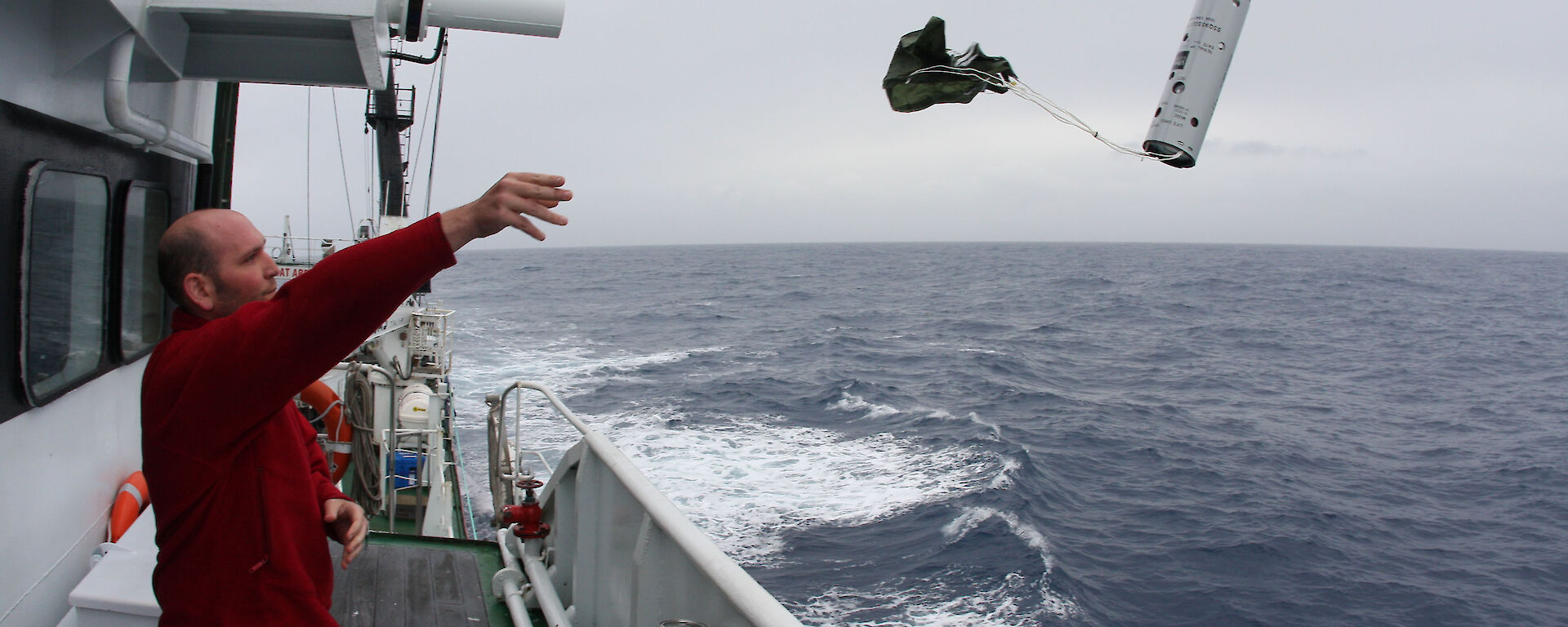

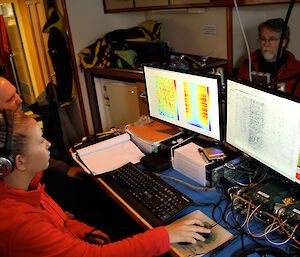

‘Sonobuoys have been used to record whales for at least 30 years, but we’ve refined the technology to the point where we can hear and track the whales in real time,’ he said.

‘We do this by analysing the whale songs for pitch, duration, intensity of sound, rhythm and direction. A single sonobuoy can ensure that we are always moving towards a new group of blue whales. As we approach and the intensity of the calls increases, we deploy multiple sonobuoys to triangulate the whales’ position.

‘Using this method we located whales to within a few kilometres; close enough for the visual observers to spot them. Our success rate on this voyage was very high and we detected whales up to 600 miles away.

‘I’m hopeful we’ve provided a new blueprint for future whale voyages.’

Voyage science coordinator, Dr Jay Barlow, from the Southwest Fisheries Science Centre in La Jolla, US, agreed.

‘The most exciting achievement is that we have the ability now to find blue whales in the really thin soup that is blue whales in the Southern Ocean,’ he said.

‘Before the advent of whaling there used to be 200 000 blue whales in these waters and today there’s less than two percent of that number, so it’s really hard to find them. This acoustic technology allows us to find them with unprecedented speed and accuracy.’

Dr Miller and his colleagues made 626 hours of recordings in the study area, with 26,545 calls of Antarctic blue whales analysed in real time. Once the whales were located, a team in a small boat was deployed to gather photo identifications and skin biopsies.

‘With photo identification data you can estimate population abundance, you can delineate stock structure between different populations of blue whales and you can track movements on fine and large scales, such as migrations routes,’ said lead observer Paula Olsen, from the Southwest Fisheries Science Centre in San Diego, US.

Skin biopsies allow scientists to obtain DNA profiles of individuals, which will contribute to an existing DNA database. Now and in the future, these samples will allow scientists to determine if they see the same animal multiple times on one voyage, or different voyages, providing information on movement within and between seasons.

Dr Virginia Andrews-Goff, from the Australian Antarctic Division, enhanced this data collection when she successfully deployed two satellite tags from the bowsprit of the small boat.

The tags, which send location data to the ARGOS satellite system, will provide information on how the whales move between their breeding and feeding grounds and what they do in their feeding grounds.

Within the first few days after tagging, the whales travelled over 100km a day. The first tagged whale initially travelled north and by early April was 2000km to the west of its original location and far removed from the ice edge. The second tagged whale travelled southwards, straight to the ice edge, covering almost 2000km in two weeks. The tags will continue to transmit the location of the whales until they fall out.

‘This was the first time, to my knowledge, that Antarctic blue whales have been tagged, although blue whales have been tagged elsewhere,’ Dr Andrews-Goff said.

‘Being so close to an Antarctic blue whale is mind-blowing and slightly intimidating. I felt as though I was the size of an ant next to one. When I tagged that first Antarctic blue whale I was in a state of disbelief. But once my colleagues confirmed that it had actually happened, I was grinning from ear to ear.’

Australian Antarctic Division Chief Scientist and cetacean expert, Dr Nick Gales, said the information gathered on the voyage will contribute to the conservation and management of the species through the International Whaling Commission.

‘Like many whale species, Antarctic blue whales came close to extinction as a result of whaling. But the recovery of this species is a lot slower than that of other whale species and it’s our responsibility to understand what might be impeding that recovery and to do something to ensure they become a more common sight in the Southern Ocean,’ he said.

‘The data collected on this voyage will contribute to our understanding of how many Antarctic blue whales there are, where their populations are, where they feed and how they interact with their environment.

‘We’ll share our results with the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission to inform conservation and management policies for this species.’

Dr Gales said the success of the voyage would have even further ramifications.

‘This voyage has demonstrated a new way of working with whales in the high seas, using listening devices and small boats to get close enough to obtain photographs, acquire genetic material and to deploy satellite telemetry technology,’ he said.

‘Australia has made a strong case for a long time, that information for whale conservation can be acquired using non-lethal techniques. This voyage proves you can get all the information you need without killing them.’

Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division

Read more about the Antarctic blue whale voyage.

* The Southern Ocean Research Partnership currently involves Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, France, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa and the United States.