A new molecular test will allow scientists to identify the sex of juvenile and sexually ‘regressed’ Antarctic krill, for the first time.

The test, developed by Dr Leonie Suter and her colleagues at the Australian Antarctic Division and the University of Padova in Italy, will provide insights into some of the unusual features of krill reproductive biology.

It will also help researchers identify the gender distribution within swarms.

“The ratio between males and females in krill swarms is often very uneven,” Dr Suter said.

“On a recent voyage, we found one krill swarm contained only seven per cent females, while another was made up of 82 per cent females.

“This gender bias could affect the reproductive capacity of the swarm, or the behaviour of the swarm, as males surrounded by males might act differently to when they’re surrounded by females, and vice versa.

“We don’t know how widespread this biased sex ratio is or what causes it, and determining whether there is a pattern to the distribution of these swarms could improve conservation measures and fisheries models.”

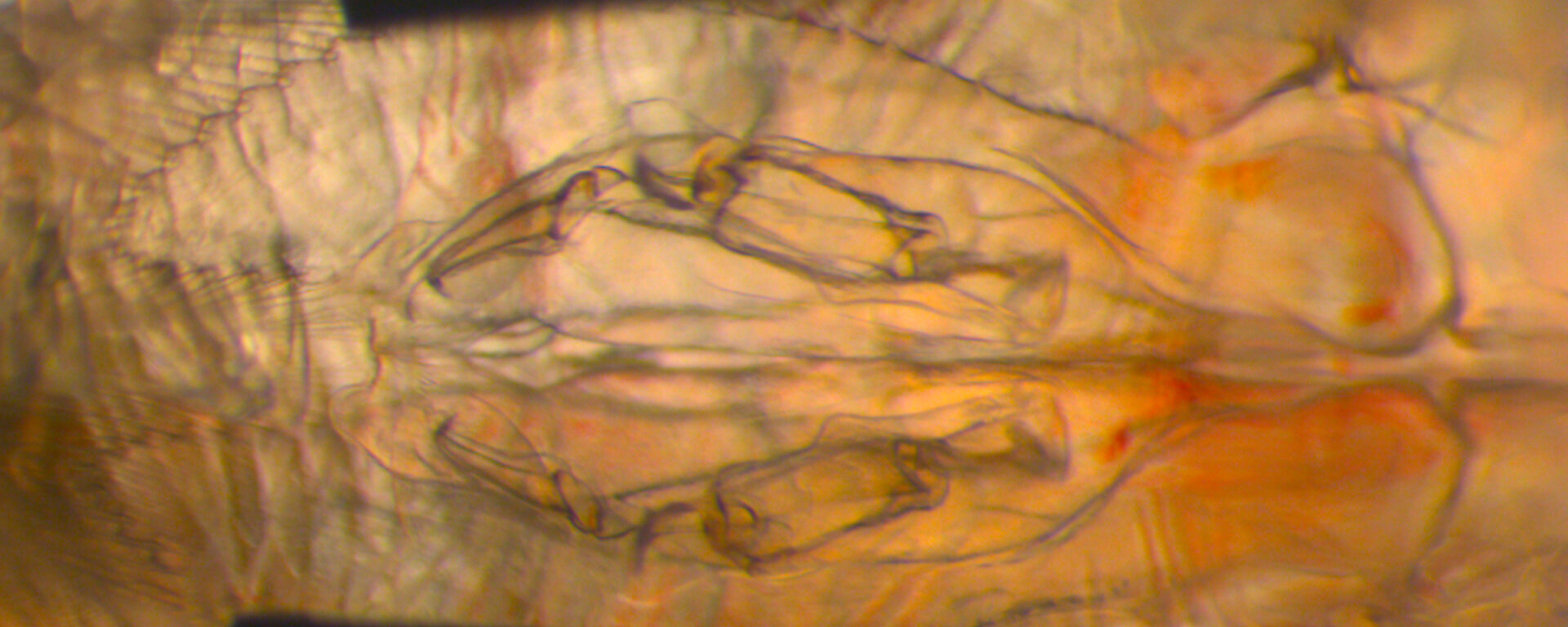

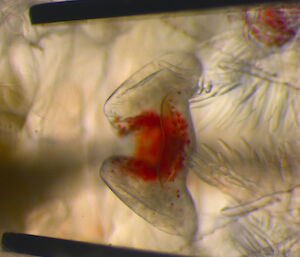

But there’s a catch. To identify the sex of krill, tell-tale physical characteristics have to be examined under the microscope, but these are only present in sub-adult and adult krill.

Larval and juvenile krill lack these characteristics, and over winter when food is limited, adult krill can shrink in size and revert or ‘regress’ to a form without external sexual structures.

While finding a gene responsible for male or femaleness would be ideal, the krill genome is complex and 15 times larger than the human genome, so only a small amount of the DNA has been sequenced.

However the presence of genes related to sexual development can be identified using RNA (ribonucleic acid), which is produced from DNA when genes are actively expressed.

So Dr Suter examined the RNA in krill testes and ovaries to identify genes expressed in these tissues.

“There were extensive gene expression differences between ovary and testis tissue, meaning that although the same genes are present in males and females, many are activated or expressed in a sex-specific way in their gonads,” she said.

She then looked to see which of these differentially expressed genes were present in either whole female or whole male krill.

“We found three genes that were only expressed in females and that these could reliably determine the sex of juvenile, sub-adult, adult and sexually regressed krill, but not larval krill,” she said.

“Using these genes we’ve been able to develop a molecular test for unambiguous sex determination of krill lacking external sexual characteristics, for the first time.

“This will contribute to our understanding of krill population dynamics, genetic diversity and reproductive behaviour.”

When it comes to sex, even amongst krill, it’s complicated.