Australian Antarctic Division acoustician, Dr Brian Miller, and consulting ecologist Dr Elanor Miller, made the chance discovery while reviewing six years of acoustic recordings made for a blue whale and fin whale study.

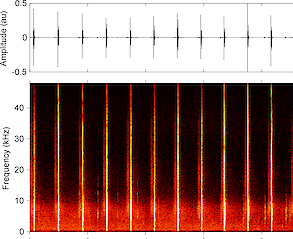

They found thousands of hours of loud ‘usual clicks’, which have the regular, even beat of a metronome, and are used to echolocate prey such as fish and squid.

“Sperm whales have four types of vocalisations — slow clicks, usual clicks, creaks and codas,” Dr Brian Miller said.

“Slow clicks and codas are thought to be linked to communication, while usual clicks and creaks are linked with echolocation and foraging.

“Usual clicks are produced about 80 per cent of the time the whales are underwater, which makes the whales very easy to detect acoustically.”

Faced with more than 46 000 hours of recording data from moorings deployed at three sites off East Antarctica, the pair wrote an algorithm to detect when sperm whale clicks occurred in the recordings. This reduced the length of recordings to be manually checked to 1065 hours.

“The recordings showed that sperm whales were only present in summer and autumn in the Antarctic and they departed our study sites when sea ice became heavy,” Dr Miller said.

“We also found that that the whales predominantly foraged during daylight hours and were silent at night, possibly due to the behaviour of their prey.

“This is the first study to directly measure the seasonal presence and daily behaviour of sperm whales in Antarctica.”

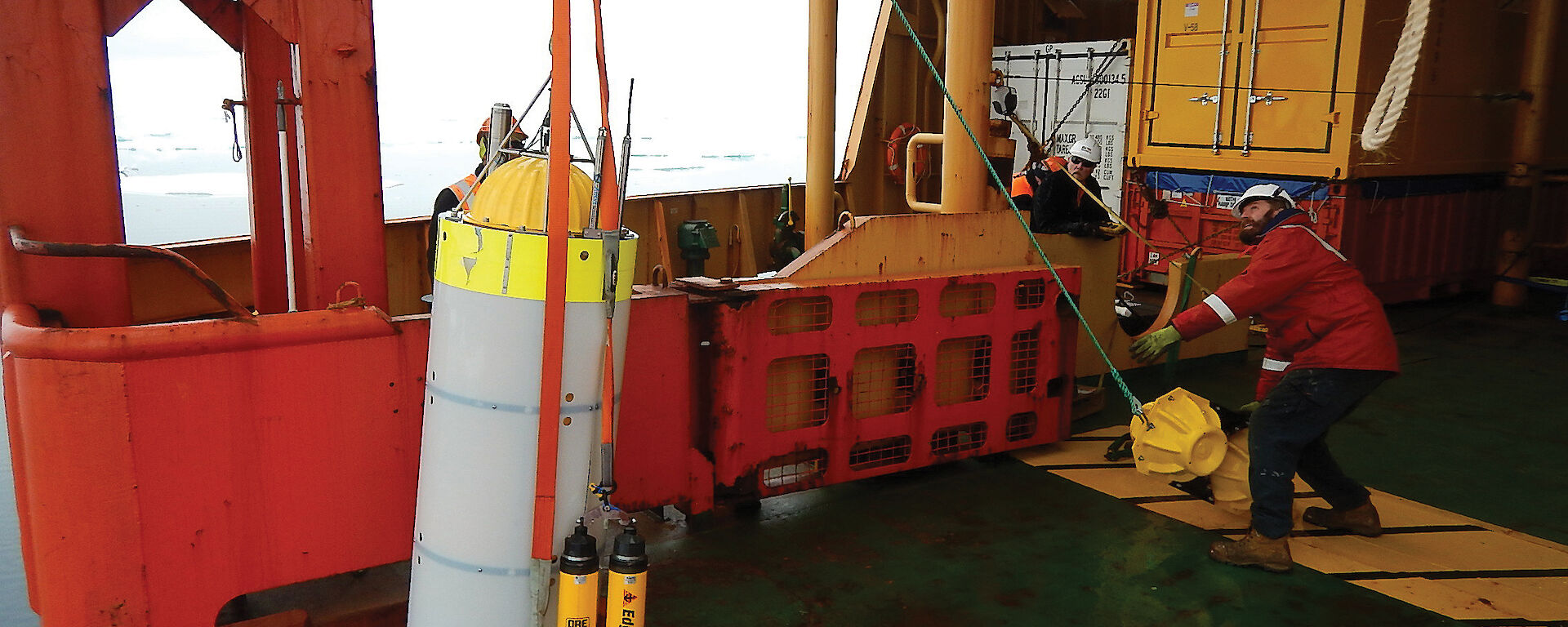

The recordings were made using equipment designed and built by the Australian Antarctic Division Science Technical Support team.

Electronics Design Engineer, Mark Milnes, said ocean sounds are detected by a hydrophone and recorded on to SD cards inside a vacuum-sealed glass chamber, which can withstand 0°C water temperature at depths of up to 3500 metres. The recorder can run continuously for more than a year.

“The glass recording chamber sits within a specially constructed frame that can be easily deployed and retrieved from the rear deck of the Aurora Australis during resupply voyages,” Mr Milnes said.

“Weights keep the frame grounded on the sea floor, while buoys keep the mooring upright and eventually allow it to float to the surface when an acoustic release from the weights is triggered. When the mooring reaches the surface, a satellite beacon provides a GPS location to the ship.”

The technology has enabled scientists to gain new insights into the behaviour and ecology of sperm whales in the Antarctica. Sperm whales are a key predator in the Southern Ocean ecosystem and the work will inform environmental management decisions for this vulnerable species.

“These studies are an important stepping stone for measuring the number of sperm whales using Antarctic waters,” Dr Miller said.

“As acoustic technology continues to develop, our ability to glean information from these underwater recording devices is going to improve.

“This is frontier science and we’re potentially hearing things that have never been heard before.”

The research was published in Scientific Reports in April.

Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division