New research using climate data from ice cores, corals, sediment layers and tree rings has found human-induced global warming began about 180 years ago; much earlier than previously thought.

The study published in the journal Nature in August, charts warming from its earliest stages, beginning in tropical oceans and the Northern Hemisphere, and in the Southern Hemisphere several decades later.

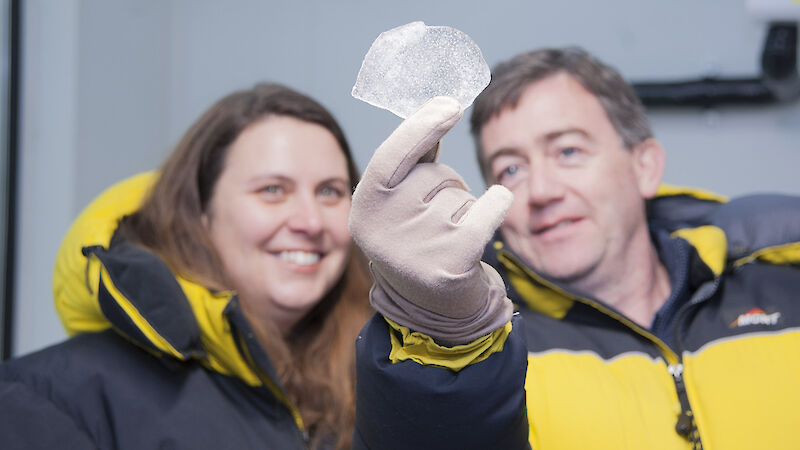

The research was led by Associate Professor Nerilie Abram from the Australian National University and involved a team of 25 scientists from the Past Global Changes 2k Consortium (including scientists from Australia, United States, Europe and Asia).

Australian Antarctic Division climate program leader, Dr Tas van Ommen, said significant human-induced warming was previously thought to have been a 20th century phenomenon.

“The new climate data analysed in this research stretches back 500 years and allows us to see warming in its earliest stages, progressing across the globe,” he said.

“It shows the Earth’s climate is sensitive to even small changes in greenhouse gas levels, providing a valuable context for modelling future climate.”

As well as examining natural climate archives (such as ice cores), the research team analysed thousands of years of climate model simulations — including those used to inform the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

They found that warming did not develop at the same time across the planet.

“The tropical oceans and the Arctic were the first regions to begin warming, in the 1830s, while Europe, North America and Asia followed some two decades later,” A/Prof Abram said.

“Warming in parts of the Southern Hemisphere was delayed up to 50 years, and the Antarctic continent is yet to show significant overall warming.”

However, the study did find significant regional warming in West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula since the mid-20th century, with warming in these areas among the most rapid seen anywhere on the globe.

The research team said Antarctica has generally been buffered from major continent-wide changes due to its thermal isolation, with the Southern Ocean muting warming.

“The Southern Ocean currents that flow around Antarctica tend to move warmer surface waters away from the continent, to be replaced with cold deeper water that hasn’t yet been affected by surface greenhouse warming,” A/Prof Abram said.

“The westerly winds that circle Antarctica also reduce warm air reaching the continent. Ozone depletion and rising greenhouse gases have acted to make this wind barrier stronger.”

A/Prof Abram said that by pinpointing the date when human-induced climate change started, scientists can begin to work out when the warming trend broke through the boundaries of the climate’s natural fluctuations, because it takes some decades for the global warming signal to “emerge” above the natural climate variability.

“According to our evidence, in all regions except for Antarctica, we are now well and truly operating in a greenhouse-influenced world,” she said.

“We know this because the only climate models that can reproduce the results seen in our records of past climate, are those that factor in the effect of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by humans.”

The early onset of warming also means that the Earth is closer to the 1.5–2°C warming limit agreed at last year’s Paris climate summit.

“Instrumental records indicate that 2016 is on track to be 1.3°C warmer than when those records began in the late 19th century, but a couple of tenths of one degree needs to be added to that figure to fully account for how much humans have changed the climate since industrialisation,” A/Prof Abram said.

However, given how quickly the climate responded to the small increases in greenhouse gases in the early 19th century, there is potential for it to respond quickly to small decreases.

“If we can do anything to slow down greenhouse gas emissions, or even start to draw them back, there may be at least some areas of the climate system where we get a rapid payback,” A/Prof Abram said.

Corporate Communications

Australian Antarctic Division