Down the years, in some parts of the world, albatrosses and people have had a hard time living together. Albatrosses have been shot and clubbed to near-extinction for feathers and meat, they’ve been fire bombed and bulldozed to make way for airfields, and the waters they feed from have been so polluted by industrial waste that vast numbers of chicks have died from junk fed to them by their parents. That they’ve survived all this is a credit to their powers of regeneration, but the newest threat — death by drowning in longline fisheries — is relentless and the birds could become extinct if mortality rates remain unchecked.

The 24 species of albatrosses roam the world’s oceans south of 30°S and north of 30°N, for these are the windiest latitudes and albatrosses need the wind to fly. They’re remarkable fliers, and it takes only a mild stretch of the imagination to think that an albatross living at, say, the Chatham Islands in New Zealand but wishing to cross the Pacific to rich South American feeding grounds could on the same day have breakfast in New Zealand, lunch in Tahiti and dinner off the coast of Chile or Peru. The time span for this flight might be fanciful but the implied ease in traversing one of the world’s largest oceans and the ability to feed in someone else’s waters are not. And this is why albatrosses get into trouble: distance is no problem and they prefer the same waters as do longline fishing vessels. These waters lie over continental shelves and their margins and along frontal zones where water masses mix and upwell. Longline vessels frequent these areas targeting pelagic fishes (i.e. tuna, swordfish) and bottom-dwelling fishes (i.e. ling, hake, cod, halibut, sablefish, Patagonian toothfish) on longlines that might measure 130km in length and carry as many as 40,000 hooks. Longliners also discharge waste from processed fish which not only supplements the diets of seabirds but encourages them to stick around, thereby exposing them to line setting operations when baited hooks are deployed.

Albatrosses get hooked (and drowned) when they attack baited hooks that are set without protective measures (the most effective measures are setting lines deep underwater, setting lines at night, adding weight to speed up sinking rates, flying streamers to scare birds off baits, disguising baits with dye and discharging fish offal discretely). In the Southern Ocean, where most albatross species range, it is likely that tens-of-thousands of albatrosses and other petrel species are killed annually, and this is threatening the survival of many populations.

Mortality is probably highest in the illegal fishery for Patagonian toothfish, where pirate vessels don’t carry independent observers and probably don’t use protective measures., It is also high in the Indian Ocean for tuna, because of the large number of albatrosses in that part of the world, the difficulties of managing fisheries in international waters and the lack of observers on vessels.

A peculiarity of the problem is its invisible nature: the total number of albatrosses caught, particularly by individual longliners, is usually quite low, and this is one reason why sectors of the fishing industry have resisted the notion that their industry causes populations to decline. The explanation lies in the nature of the birds themselves: albatrosses are long lived, take a long time to mature and they don’t breed like rabbits. Push mortality above levels they’re not designed to cope with and you start an insidious slide into the abyss. And getting fishermen to see the problem is the hard part, because unlike the harvesting for meat and feathers mentioned above — which occurred on land and could be seen if not measured — mortality from longlining occurs at sea, is often out-of-sight and out-of-mind, hard to measure and very difficult to control.

Albatrosses are hard-wired by Nature to do what they do and can’t be changed — diving down on fish near the sea surface is a difficult behaviour to modify! What can be changed is the attitude of agencies and people responsible for the stewardship of the oceans, and change is occurring, albeit slowly. Solutions are being developed at international and national levels, by governments and researchers and by some fishermen. The initiatives of greatest importance, because of their global co-ordination roles, are those by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, the Global Environment Fund and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.

The FAO has produced an international plan of action to reduce seabird mortality in longline fisheries. This calls for all nations with longline fisheries to produce plans on how they intend to deal with the problem. The production of a national plan usually involves an assessment of the nature and extent of seabird mortality by fishery type, adoption of seabird bycatch mitigation measures (which might involve at-sea research to determine best practice), inclusion of bycatch regulations in fisheries management legislation and the use of independent observers on fishing vessels. Some nations have completed their plans and several nations have theirs in the draft stage; participation is, of course, voluntary and time will tell how attentive and genuine longlining nations have been in responding to this important FAO request.

The Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels of the southern hemisphere (ACAP) stems from the listing of 14 species of albatrosses with unfavourable conservation status in the appendices of the Convention for Migratory Species of Wild Animals. As the Chatham Island example above indicates, albatrosses on migration flights frequent the waters of many nations, hence the importance of multi-nation agreements to protect them throughout their entire migratory ranges. The Agreement pertains to States that exercise jurisdiction over any part of the range of albatrosses and petrels, as well as distant water fishing nations that interact with albatrosses and petrels while fishing. Parties to the ACAP will be obliged to achieve and maintain the favourable conservation status of albatrosses in both terrestrial and marine environments. This initiative is complementary to that by the UN’s FAO since the protection of albatrosses in marine environments will require, essentially, the production and implementation of action plans as sought by the FAO.

Pivotal to ACAP success is a high degree of collaboration between participating nations at government level. Collaboration is also occurring from the bottom up. In 1999 Australia, Chile and the United Kingdom teamed up to train a Chilean PhD student in the ecology of albatrosses breeding in southern Chile, including interactions with fisheries. Destined for completion in 2002, this study is the first of its kind for a South American and is an important grass-roots attempt to generate the knowledge and human resource-base upon which the albatross conservation effort depends.

Another initiative of international significance concerns the Global Environment Fund (GEF). This year a BirdLife International sponsored meeting will be held in Cape Town to prepare an application to the GEF seeking financial help for developing nations to produce plans of action to FAO requirements. Countries that stand to benefit include South Africa, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil. The waters of these nations support large longline fisheries and are rich feeding grounds for albatrosses from many parts of the world.

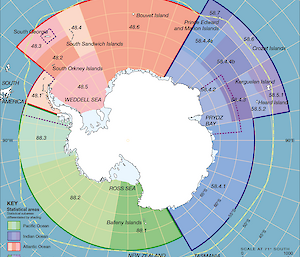

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) is a 23-nation organisation responsible for overseeing the ecologically sustainable use of living resources in the Southern Ocean, and has been a leader in attempts to get albatrosses off the hook. The CCAMLR area (see map in image gallery above) includes the entire Southern Ocean from Antarctica to the northern limits of Antarctic waters, which is roughly about half way between the Antarctic continent and Australia: this area also includes many albatross breeding islands and foraging waters. So far as albatrosses are concerned, longline fishing in these waters means the legal and illegal fisheries for Patagonian and Antarctic toothfishes, which occurs from 500–2,500m deep around the margins of Antarctica and subantarctic Islands and the coasts of Chile, Argentina and Uruguay. Since 1995 CCAMLR has promoted the use of albatross-friendly fishing practices in the legal toothfish fishery with mixed results. Even with the existence of easy-to-use mitigation measures seabird mortality has remained unacceptably high, principally because of the lack of full compliance with the measures and because of fundamental difficulties with one of the established methods used to catch toothfish. Consequently the toothfish fishery around South Georgia, an island in the southwestern Atlantic Ocean with one of the largest toothfish quotas, is closed during the eight month albatross breeding season. This most heavy-handed of measures has been necessary to take seabird mortality to safe levels (in the 2000 season 14.5 million hooks deployed caught <50 seabirds) and has encouraged some fishermen to try catching toothfish with craypot-like cages instead of hooks.

The biggest challenge for CCAMLR is the illegal toothfish fishery, which is about the same size as the legal fishery. To reduce the sale of fish caught by unlicensed vessels CCAMLR has sought the cooperation of countries offering port and downloading facilities to the illegal trade and introduced a documentation scheme for legally sold fish, the idea being that vessels must produce evidence of licensed fishing in order to sell their catch. However, poaching toothfish and selling it illegally is a lucrative business and only time will reveal the effectiveness of the scheme in curbing the illegal toothfish trade and the associated take of albatrosses and other seabird species.

The initiatives outlined above paint a picture of international effort, conservation agreements, funding for developing nations and implied change, but it would be a mistake to believe that satisfactory outcomes lie just around the corner. The picture isn’t as rosy as it might seem. As the South Georgia example indicates (where fishery closure was necessary to achieve albatross conservation objectives) the existence of effective mitigation and neat international agreements don’t necessarily translate into seabird-friendly fishing practices. Unfortunately the realities of human nature and vested interest tend to get in the way.

When it comes to international agreements, nations are like the people in them: they want to be wanted, to know they matter and to exert influence over issues affecting them — better to be in than out as the saying goes. But the spectre of disingenuousness hovers ever-present in the background: often the tendency is to sign agreements then hurry up and go as slow as possible in effecting real change, to log jam progress in order to preserve the status quo. This behaviour is an unfortunate fact of international life and it’s the reason why a persistent top-down approach by people trained to argue with the equivalent of brick walls is an integral part of the global albatross conservation effort.

The key concern is what happens at sea, for this is where each day during line setting operations fishing masters make decisions that determine whether or not albatrosses will get hooked and drowned. With 6 metre seas to deal with, 18-hour working days, months or even years away from home and sweatshop working conditions, it’s understandable why decisions by governments and even land-based vessel owners about seabird conservation tend to be neglected. The reasonable expectation however, is that vessel owners and fishing masters be pragmatic enough to realise that sustainability is the way of the future and that it pertains not only to target fish species and fishermen themselves but to bycatch species as well, including albatrosses and other seabirds.

Aggravating the situation is the over-abundance of fishing vessels in the world and the global trade in seafood: both encourage illegal fishing and fishing in breach of international agreements intent on sustainable management. The FAO is attempting to reduce the number of fishing vessels in the world, via an international action plan, but this initiative will almost certainly meet considerable resistance and it would be remarkable if anything emerged in the short-to-medium term that was of benefit to albatrosses.

The global trade in seafood encourages overfishing, which means more hooks deployed and more albatrosses caught. Conservation usually works best when nations can see and take responsibility for the environmental effects of lifestyle and consumption, and this can’t happen if rich nations import fish taken from international waters or the waters of nations that need the money, and push their fisheries to the limit. To manage fisheries properly you need your hands on the wheel, and it would make better sense if fishing nations developed the capacity to feed themselves from their own economic zones where a sense of ownership can exist and the sustainable management of fisheries would be more likely.

So, can albatrosses and longline fisheries co-exist? This question can be answered in two parts — co-existence inside national economic zones and co-existence in international waters (it’s easiest to break the question in two, but in reality the dichotomy is a spatial nonsense and conservation success relies on a co-ordinated effort both inside and outside of economic zones). Co-existence between albatrosses and longline fisheries inside national economic zones should be possible but relies on several assumptions: that relevant nations produce effective plans of action, that seabird conservation measures are woven into the fabric of fisheries management legislation (including the potential for punitive action against violators of conservation measures) and that adequate observer coverage of vessels exists, In international waters though it’s a different story. In the absence of a panacea (a fix-all mitigation technique that fishermen find beneficial) we are left with voluntary compliance, and that doesn’t inspire confidence. I don’t expect fishermen to care about seabirds and I don’t expect them to use mitigation measures unless they benefit the fishermen — worrying about seabirds doesn’t fit well with the culture and practice of longline fishing and the money-making imperative that drives it. In international waters, unless something unexpected happens — like collapse of fish stocks or contraction of fisheries to waters not frequented by albatrosses — then albatrosses and some other seabird species will continue to be taken in large numbers and further population reductions will be inevitable.

Graham Robertson

Antarctic Marine Living Resources Program,

Australian Antarctic Division