Tim Low travelled to Antarctica as a Fellow in the summer of 03/04. Tim is a Brisbane-based nature writer and photographer with qualifications in both science and journalism. He has written extensively for Australian nature magazines and journals, and three of his six books have won literary prizes. Currently with more than 100,000 book copies in print, Tim Low’s proposal was to write two books as a result of a voyage to Antarctica, one of them a book about birds. He also proposed a ‘store’ of stories and photographs that will be used in future books and articles.

Tim’s writing style attracts readers from scientific and general backgrounds, with science, nature, anecdotes and travel experiences all woven together.

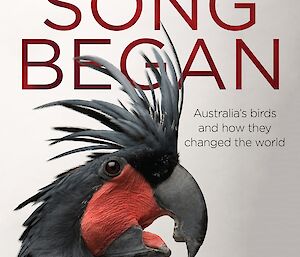

In 2014, Tim’s book Where Song Began: Australia’s Birds and How They Changed the World was published by Penguin Books Australia. In the chapter about seabirds he has a section, ‘Sleeping on Air’, that recounts the experience of travelling to Antarctica on board the AAD’s icebreaker, the Aurora Australis:

“Birds went to sea so early in their history that there were birds in water long before there were birds without teeth. A life at sea was not something I could comprehend until I ventured out in it myself, as a guest on the Australian Antarctic Division’s ice-breaker, the Aurora Australis. I was shown a new world.

Within three days of our leaving Hobart, 60-knot gusts had whipped the ocean into a foamy mess. Spray hit our windows high on the bridge, and the bow kept plunging into giant chasms that opened in the dark water before us. From the warmth of the heaving bridge all this was sinister enough, but to step outside onto the exposed decks was to feel fear strike like a slap in the face.

How were the birds I’d been seeing coping with this cyclone that we were now inside? They had no land to retreat to. The shadowy shapes of a few shearwaters glimpsed through wave-splattered glass did not tell me much. But then, like an apparition, something white floated before the bow, moving much too slowly and smoothly for the circumstances. In all that cold confusion it was the one stable thing, a wandering albatross, one wing trailing above a rush of foaming water.

My heart jumped for its safety, until I saw how at ease it was. I understood the awe these birds inspire in those who enter their domain. The weather map on the bridge showed a procession of cyclones round the Southern Ocean, promising turbulence in all directions

for hundreds if not thousands of miles. Day after grey day the world stayed wild, though the sea was sometimes less extreme. The log filled with entries about ‘pitching and rolling’ in what was often a ‘heavy confused swell’. I saw why sailors in ships of creaking wood so feared the Roaring Forties.

Quiet stole over our ship as the sick hid in their beds, but the birds never showed any discomfort, neither wavering in flight nor opting to rest on the ship. So safe is the sea for albatrosses that if they survive longline fishing they outlive most animals on earth. One royal albatross was laying eggs and rearing young years after the scientist who banded her fifty-eight years before had gone to the grave.

One sleepless night, I passed the hours of sliding back and forth in my bunk by wondering how the birds were spending theirs. Many seabirds sleep at night, but surely, I thought, not on breaking seas. There was nothing stable for a bird to rest on. Can seabirds sleep on the wing?

Most experts think so.”

In chapter 7 he describes the experience of being on Antarctica trying to imagine what it looked like during the late Cretaceous, when it still had a connection to Australia, via a column of land running through Tasmania.

“In the Antarctic twilight, I have perched on a pink outcrop near the abandoned Wilkes Station while calving ice struck the sea, sounding like cannon fire, and tried to visualise beeches and conifers growing there, like those in New Guinea, New Zealand and Tasmania. Pollen dredged from the nearby seabed by Douglas Mawson’s polar expedition confirms that rainforest once dominated the Antarctic coast. The scrubbier rainforests further west, around

Prydz Bay, must have had small birds pollinating some of the twenty-eight Proteaceae species identified from ancient pollen. The birds could have migrated in winter across the narrow seaway that, by 84 million years ago, separated Australia from Gondwana, or travelled along the lingering land connection that ran through Tasmania to the mainland. Antarctica’s only small birds today are Wilson’s storm-petrels, one of which hovered near me like a dark swallow, investigating gaps between rocks.”

Antarctic impressions

“A new continent, my first experience of the open ocean, and a subantarctic island. As an ecologist I experienced three major new habitats: the Great Southern Ocean, Antarctica, and a subantarctic island.

I was amazed to learn that the ridges around Casey match up with rock outcrops on the south coast of Western Australia. They mark a line where Antarctica and Australia sheared apart many millions of years ago. Only a couple of years ago I was standing on a rocky shore in Western Australia looking south into the ocean and thinking about Antarctica. On this trip I had the chance to stand on the opposing shore in Antarctica and recall that rocky place way to the north, trying to imagine them once joined together. The experience has greatly broadened my sense of Australia and Australian wildlife and I look forward to weaving in stories in future books and articles.”

An article by Tim Low about Australia’s islands appeared in the Australian Geographic magazine in June 2006, mentioning Tim’s experiences on Macquarie Island.

'Polar Invaders' appeared in the December 2004 issue of BBC Wildlife magazine, Britain’s leading nature magazine. This article highlights the risk that tourists and tourist vessels can pose to Antarctica by unintentionally introducing exotic organisms such as weed seeds and insects.

'Growing Old in the Cold' appeared in the March 2005 issue of Nature Australia magazine, for which he wrote a regular column. This article discussed plants in Antarctica — lichens, mosses, algae, higher plants — and the extreme conditions they grows under.

Later in 2005, Tim also wrote an article for Nature Australia about plants on Macquarie Island.