Friday 19 October

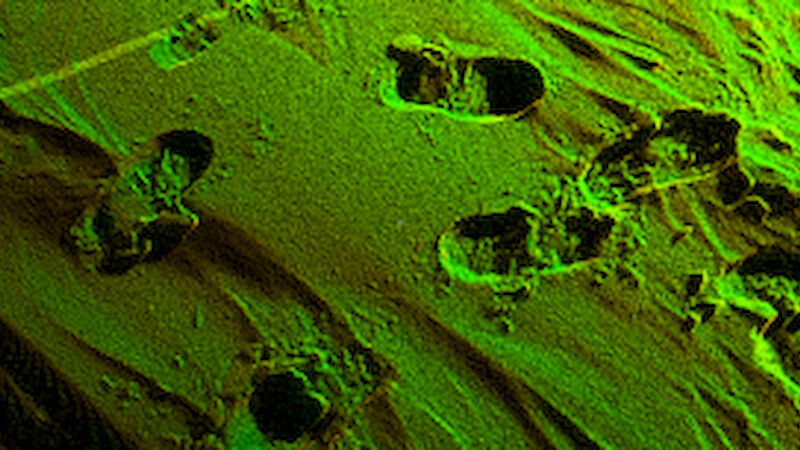

Looking more like a moonscape than a snow-scape, these amazing images were captured by Dr Ernesto Trujillo-Gomez of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland, using a terrestrial laser scanner.

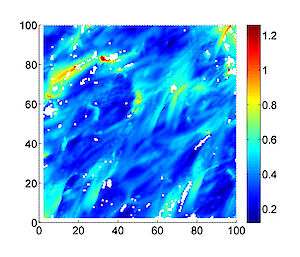

The terrestrial laser scanner directs green laser light on to the snow surface and measures the time it takes for the light to bounce back. This reading provides a measure of distance and angle to the scanned points which, when combined with local geographic coordinates, provide high resolution detail of the surface structure or ‘topography’ of the snow surface within a defined area (a 100 x 100m grid on this voyage). The laser has a range of about 300m and can scan objects at an accuracy of within 5cm at 100m, with an even greater resolution closer to the laser.

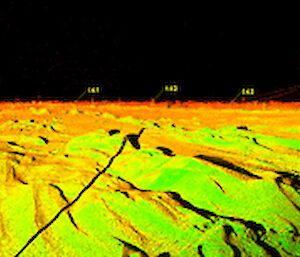

Ernesto makes at least three scans of the target area from different angles to get a 360 degree view. The different angles allow him to ‘see’ around objects in the snow, such as rafted ice or snow drifts that block the laser’s sight of the snow surface behind. He then aligns the different scans using target markers (circles on a stick), which he has precisely located in the survey grid.

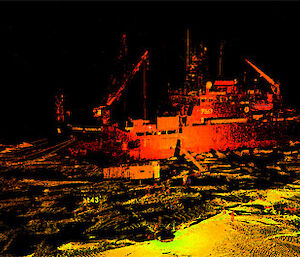

Each scan takes about 50 minutes and provide some 20 million data points. Once the scans are combined Ernesto has about 50 million data points. These appear as dots in the final product — each only 2mm apart in some areas — and make up the final high resolution image. The scans are so detailed they show every bump or undulation in the snow and any penguin that stood around for long enough.

In these pictures you can see footprints, flags and target markers placed in the survey area, details of our ship, and even people milling about in front of it. The different colours represent different scans and black areas show areas the scanner was unable to see behind — these areas will be filled in once all the scans are combined.

These snow surface scans, in combination with snow depth measurements and under-ice measurement made by the Remotely Operated Vehicle and the Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (see previous blog post), will contribute to a three-dimensional picture of snow and ice thickness and topography.