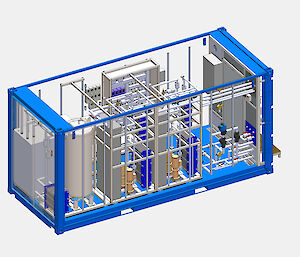

The new ‘science modules’ are an integral part of the ship’s design, with pipes and cables already installed on the ship to provide power, water, vacuum and air directly to the modules’ standardised ‘service interfaces’.

Australian Antarctic Division Instrument Workshop Manager, Steve Whiteside, said the science modules form part of a larger containerised capability on the ship, which has space for up to 13 laboratories and 11 science support facilities (for storage and mechanical equipment).

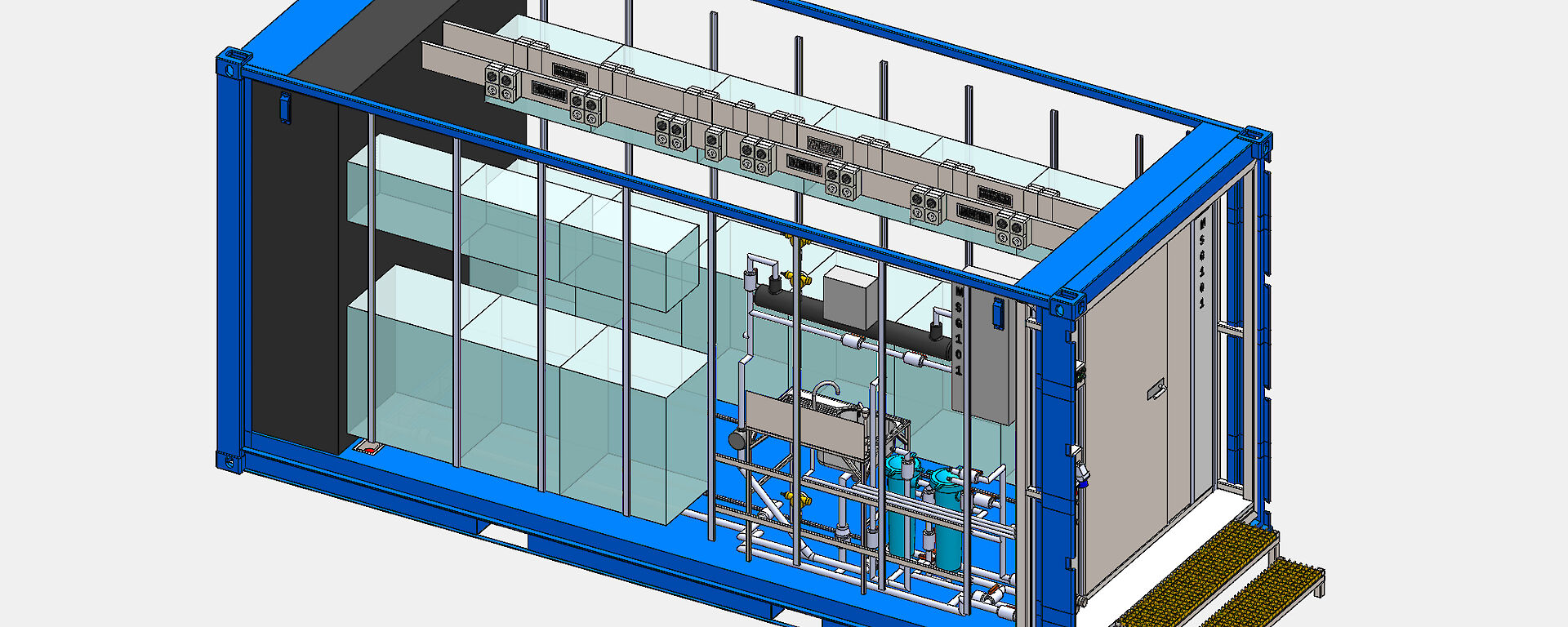

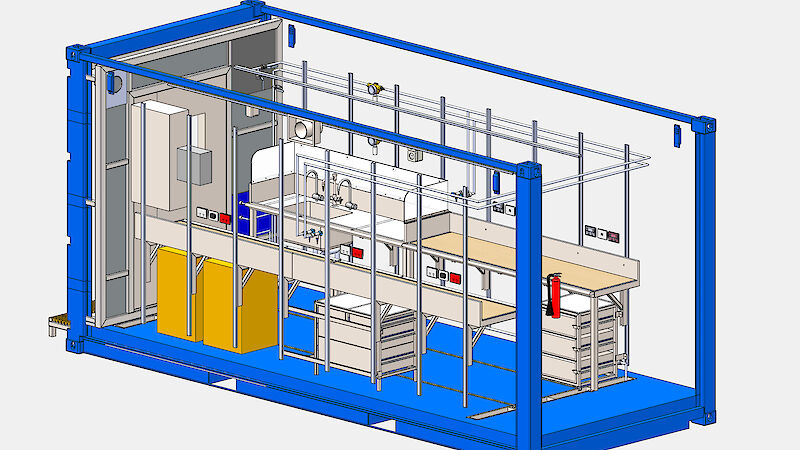

The six modules include a general laboratory, a temperature controlled laboratory for temperature-sensitive experiments, an explosive gas laboratory for the use of hydrogen, two aquaria for krill and fragile marine organisms, and a container for the aquaria mechanical equipment.

“The Nuyina is a big step forward in scientific capability because half the space is fixed laboratories and the other half is flexible space in the form of science modules and other 20- and 10-foot containers,” Mr Whiteside said.

“The modules have been designed so that they can be pre-configured for different science projects before they’re loaded on to the ship, and they can be plugged directly into the ship’s power and alarm systems via their standard service interface. This will save time and improve safety during the busy turnaround time between voyages.”

The modules will be built to a safety standard used for laboratories and special facilities in the offshore drilling industry. Safety features include a fully sealed steel shell and other non-combustible materials, such as rock wool insulation, designed to resist fire from inside and out. Their gas and fire detection systems will also shut down power automatically and alarm the ship.

The modules will be built and certified to the required safety standard (DNV-GL 2.7.2) based on detailed design drawings and material specifications provided by the Antarctic Division. However Mr Whiteside’s team and the Antarctic Division’s krill aquarium scientist, Rob King, will fit-out the aquaria and aquaria mechanical containers, due to the complexity and specialist nature of the job.

“Contamination is a big issue for the aquaria, and everything that has contact with sea water has to be built from inert materials, such as titanium and silicone, so that poisonous metals or chemicals don’t leach into the water and kill our organisms,” Mr King said.

To design the aquaria Mr King drew on his 25 years of knowledge working in the Aurora Australis’s krill aquarium and the Antarctic Division’s unique land-based facility at Kingston, to present Mr Whiteside with his ideal containerised version.

“The main constraint for us is space and Rob had an infinite requirement for a finite space,” Mr Whiteside said.

“Our job was to bring an engineering reality to the design and work with Rob to model and tweak it until we came up with something that worked for both of us.”

The end result is an aquarium system that can accurately control the temperature of seawater no matter the location of the vessel, and maintain two aquaria containers at different temperatures, anywhere from −1.5°C to 15°C.

“We will have gigalitres of clean seawater available to us to keep our animals healthy, but it won’t always be at the right temperature, so we’ve had to design an efficient temperature exchange system,” Mr King said.

“On our way south we might catch some organisms in temperate or sub-Antarctic waters, and we’ll be able to maintain them at that water temperature for the whole voyage. We can also hold animals collected in colder Antarctic waters in separate tanks, for the voyage home.

The containerised aquaria will improve the survival rate of krill during their transfer from ship to shore. Previously, krill were hand-netted from tanks in the Aurora Australis’s cold room and transferred in 10 litre buckets, packed in ice, to the Antarctic Division’s Kingston aquarium; a slow, labour-intensive process that reduced the number and quality of precious live specimens.

“Now we’ll be able to take the whole container off the ship, plug it in to our land-based aquarium facilities and then remove the specimens over a few days. This will keep the animals in good condition and reduce the rush for our staff and students,” Mr King said.

While the idea is to move towards standardised containers for the Antarctic Division’s fleet, Mr Whiteside’s team is developing a package that can be installed inside containers supplied by other national and international scientists, to hook up to the ship’s fire and gas detection systems.

With so much experience working at sea in both fixed and containerised laboratories, Mr King is excited by the safety and flexibility the new system will offer, and how much easier it will be to find his designated workspace — on and off the ship.

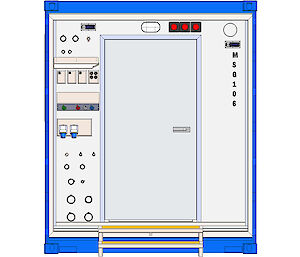

“Over the years we’ve evolved a Frankenstein fleet with so many different sized, shaped and coloured containers. Now our marine science containers will be easy to spot because they’ll all have a standard size, shape, and ship interface, and they’ll all be ‘periwinkle blue’.”

Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division