In 2018, after three field seasons of geotechnical and environmental investigations, a suitable site was identified for the 2700 metre-long paved runway, about six kilometres from Davis, in the Vestfold Hills (Australian Antarctic Magazine 34: 32, 2018).

Since then, the team has continued their geotechnical investigations at and around the ‘Ridge Site’, an elevated and undulating rocky plateau, to better inform construction requirements.

“The Ridge Site consists mostly of a very hard granitic bedrock, but the proposed runway alignment does run across two narrow sediment-filled valleys,” said the project’s Field Coordinator, Aron Gavin.

“So we’re trying to understand the ground and sub-surface conditions around these areas to work out how best to stabilise them, and the effect of that on the project.”

To understand the impacts that construction and use of the runway may have on the environment, a team of scientists has been assembled to survey the animals, plants and microbes in the operational area of interest.

“We need to get baseline data about the ecology in the area to inform the extensive environmental assessment process,” Mr Gavin said.

“This will feed into our environmental impact assessments addressing the requirements of the Antarctic Treaty (Environment Protection) Act (1980) and the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999).”

Spatial ecologist Dr Aleks Terauds is overseeing the ecological surveys being undertaken by Australian Antarctic Division scientists. “We’re aiming to get baseline information in the operational area of interest on seals, seabirds, vegetation, seabed communities, soil and lake communities, noise levels, and air and water quality,” Dr Terauds said.

“But we also want to get contextual information; so whether species are unique to the operational area, or if they occur in the wider Vestfold Hills area or throughout Antarctica.”

Seabird ecologists Dr Louise Emmerson and Dr Colin Southwell have spent years at sites around Davis, and Australia’s other Antarctic stations, studying the distribution, abundance, foraging behaviour and breeding success of Adélie penguins and flying seabirds, to inform long-term conservation and fisheries management practices.

More recently, they’ve been conducting population and migration surveys of flying seabirds, including cape petrels on the islands around the Vestfold Hills, and skuas at Rookery Lake near Davis. But it’s the Wilson’s storm petrels and snow petrels that are proving difficult to study.

“We want to understand where the birds’ breeding sites are distributed in relation to the proposed runway and aircraft flight paths so that we can assess how they might be impacted during construction and operation,” Dr Emmerson said.

“Cavity nesters like Wilson’s storm petrels and snow petrels are difficult to study because you have to crawl around on hands and knees looking into the tiniest cracks. The snow petrels also nest in cliff areas, so we can’t send teams there for safety reasons.”

This season the seabird team will put small endoscope cameras into Wilson’s storm petrel nest cavities, to see how long the breeding season lasts and when chicks hatch and leave their nests. They’ll also look for places to deploy remotely operating cameras to monitor Adélie penguin colonies near the proposed aerodrome, and they’ll attach satellite trackers to penguins to track their migratory routes across the sea ice, close to possible aircraft flight paths.

“Large numbers of Adélie penguins breed on ice-free land near Davis station between October and late February,” Dr Southwell said.

“In spring they travel across the fast-ice to reach their breeding sites and back again to their foraging grounds, and at the end of summer they have to stay out of the water for about three weeks to moult.

“At both these times it’s important that they conserve energy, for feeding their chicks or self-maintenance.

“The satellite trackers and remote cameras will help determine the energetic costs that any disturbance from the aerodrome may have.”

Also scrambling around and overturning rocks, conducting terrestrial surveys within and outside the operational area, will be Dr Dana Bergstrom and Dr Patti Virtue. They will focus on areas identified by habitat modelling as likely to contain vegetation, based on a vegetation survey at Davis station last year, and environmental characteristics such as wind, water availability and sunlight.

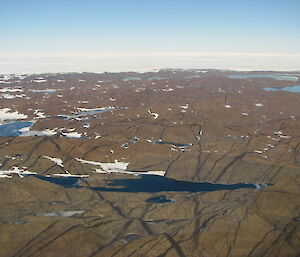

“The Vestfold Hills is a rare Antarctic oasis with a diverse range of plants including mosses, about 20 species of lichen, and a lot of algae and cyanobacteria,” Dr Bergstrom said.

“It might look like a desert, but if you get down on your hands and knees you’ll find plants growing under and within rocks, especially quartz, which acts like a mini greenhouse.

“The yellow and orange lichens are easier to see on the surface of rocks, and the cyanobacteria often form large black mats in moist areas below snow banks.

“We’ll broadly describe the presence or absence of vegetation, and its abundance, at each of our modelled locations, and any life we see as we move between these locations. We’ll also take samples for species identification.”

One of the key questions the pair will be asking is whether the vegetation-friendly habitats within the operational area of interest, also occur outside it.

The work will enable identification of useful sites for future vegetation monitoring, to tease out the impacts of climate change from that of infrastructure construction and operation.

The terrestrial surveys will overlap with lake surveys being undertaken by Dr Catherine King and Dr Kathryn Brown. The Vestfold Hills contains thousands of water bodies of varying sizes and salinities, from small ponds to lakes stretching more than four kilometres. Many of the lakes were once inundated by seawater, about 6000 years ago, and have unique properties, including hypersalinity, or discrete layers of fresh and salty water.

“Each water body is likely to not only have different physico-chemical properties, but may also be home to very distinct biological communities,” Dr King said.

“Our primary aim is to understand the uniqueness of these communities both within and outside the proposed operational area.”

The lakes team will do vertical tows for phytoplankton and zooplankton and measure water chemistry, using an inflatable rubber boat to access the larger lakes. They will also collect sediment and soil samples from the base of each lake or pond, the water’s edge, and at varying distances from each site.

“We’ll be collecting representative samples from the wet and dry zones of each lake so that we can get an overall picture of what lives within the lakes and in the transition zone between the lakes and terrestrial communities,” Dr Brown said.

Most of the samples will be analysed by microscopy back in Australia, to identify microalgae and micro-invertebrates such as ciliates, rotifers, nematodes and tardigrades, but broader community composition will also be assessed by DNA sequencing of water, benthic mat and soil samples.

Moving to the coastal zone, sea floor communities will be the focus of benthic ecologists Dr Jonny Stark and Dr Glenn Johnstone. The pair will trial a bespoke remotely operated vehicle (ROV) beneath the sea ice in fjords and other coastal locations between Davis and the proposed aerodrome area.

Among its many high-tech features (see next story), the ROV has two GoPros and a forward looking camera, to take video and stills of the sea floor, allowing operators to identify species, such as sponges, sea cucumbers, sea urchins and polychaetes (tube worms), and measure their abundance.

“Our plan is to trial some video transect and photo-quadrat methods with the ROV, so that we can come up with a methodology for a long-term monitoring program,” Dr Stark said.

“We also want to investigate suitable sites that we could survey routinely if the runway goes ahead.”

The pair will visit up to 30 sites, drilling through about 1.7 metres of sea ice to deploy the ROV.

“We’ll try and capture the diversity of habitats and we know from previous work near Davis that this could range from rocky habitats to sediment-filled basins,” Dr Johnstone said.

“The fjords will be really interesting. Work at Ellis Fjord in the 1980s found an extensive polychaete reef, stretching up to eight kilometres.”

The fjords are also home to populations of Weddell seals, which tend to haul out on the fast ice during the day, beside their specially maintained access holes.

A long-term monitoring program from the 1970s to 1990s conducted population counts on the animals, which raise pups in the area close to the proposed airstrip from October to November, returning to moult in January and February.

For the past two seasons and again this year, seal biologist Mr John van den Hoff has been coordinating the reinvigoration of population surveys of Weddell seals in Long Fjord, near the proposed runway site.

“We need to compare the locations and numbers of seals in the area and across the Vestfold Hills now, to the surveys of the past, to see if anything has changed in 25 years,” Mr van den Hoff said.

“If there’s no change, then we will have a good baseline to compare things to if construction of the runway goes ahead.

“If there are changes, then we’d need to think how to understand what’s causing the changes, and how to separate them from potential future operational disturbance effects.”

Field teams led by marine biologist Mr Andrew Irvine, will travel on foot, or by over-ice vehicle or helicopter, and count the animals from the ground or the air. They will also count them using aerial photographs and satellite images.

As well as Weddell seals, the team will count the (usually male) elephant seals that haul out at Davis research station each summer to moult, and any leopard and crabeater seals in the survey area.

Dr Terauds said that while the project will have unavoidable environmental impacts, Australia is committed to understanding and addressing the impacts to the highest standard.

“The Vestfold Hills might only represent a small part of Antarctica but it doesn’t make it any less important,” he said.

“Ninety-nine percent of biodiversity lives in ice free areas and there are elements of the Vestfold Hills that are unique, such as the number and diversity of lakes. So that’s the context of our surveys — looking at it with regard to its special values and ensuring we present the best information available upon which to base a decision.”