A paper published in Scientific Reports in August, examined the movements of 30 humpback whales tracked via satellite tags over three consecutive summers, from 2008 to 2010.

Australian Antarctic Division marine mammal scientist and the paper’s lead author, Dr Virginia Andrews-Goff, said the research* is the first to examine the foraging habits and migration path of East Australian humpbacks.

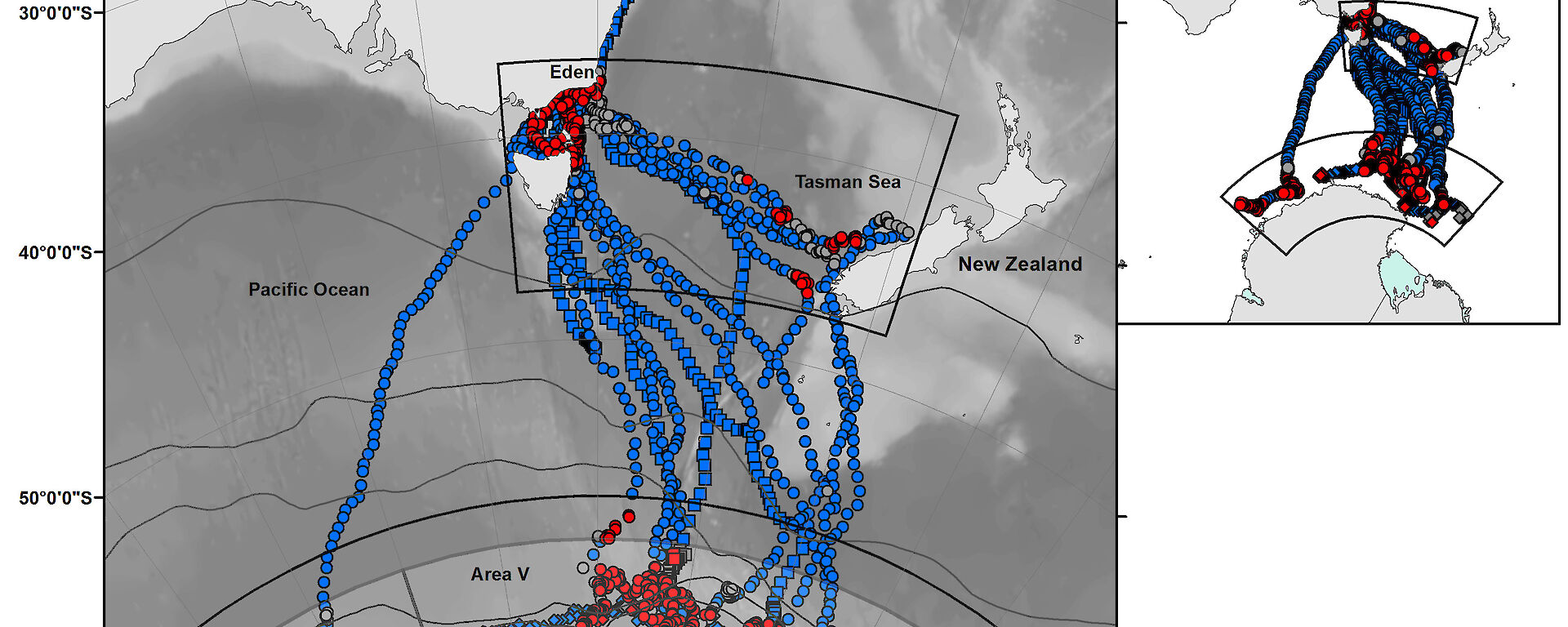

“For the first time we have been able to see the varied routes East Australian humpbacks take on their migration to Antarctica, some of which were unknown until now,” Dr Andrews-Goff said.

“The satellite data shows us they travel east via New Zealand, south via Tasmania, or west via the Pacific Ocean.”

The research also showed that the whales fed more during their migration than previously thought, spending time foraging in warmer temperate waters on their way to Antarctica. This counters traditional assumptions that humpbacks adopt a ‘feast and famine’ approach to migration — feasting in Antarctica and then fasting for the rest of the year as they migrate to and from their low latitude breeding grounds.

“As the whales migrate south they are stopping for up to 35 days to forage for krill — either off the New Zealand coast, in Bass Strait, or off the east coast of Tasmania,” Dr Andrews-Goff said.

“These observations of ‘supplemental feeding’, which have been observed in other Southern Hemisphere humpback populations, may help refuel their energy reserves prior to reaching their Antarctic feeding grounds.”

The paper also examined the characteristics of the Antarctic feeding ground, which scientists believe could be responsible for the strong recovery of the population after whales were hunted to near extinction in the 1950s and early 1960s.

“The whales time their arrival for when the ice is retreating rapidly towards the continent, and the data shows they concentrate their foraging where the ice was located two months prior,” Dr Andrews-Goff said.

“We can see that the whales move with the ice as it melts and retreats, and it’s this melt that releases new production, triggering the accumulation of Antarctic krill.”

While the marginal ice zone in the whales’ foraging area provides good foraging and protective habitat for adult and larval krill, Dr Andrews-Goff said the timing and location of sea ice formation within the area was highly variable.

“The overall trend indicates an increase in ice season duration over the past 30 years, along with decreasing sea surface temperature and primary productivity, which ultimately may result in less food for krill,” she said.

“So ongoing monitoring of the humpback population is important to understand and predict the whales’ ability to adapt.”

The research will help inform whale management and conservation policy.

Eliza Grey and Wendy Pyper

Australian Antarctic Division

*Australian Antarctic Science Project 4101