The encounter was made possible largely through the use of underwater listening devices, known as sonobuoys, which the Australian team, led by the Australian Antarctic Division’s Dr Mike Double, has trialled and refined on previous blue whale voyages (see Sound science finds Antarctic blue whale hotspot).

‘For quite a few days we didn’t hear any whales and we wondered whether there were any around. Then suddenly they “switched on”,’ Dr Double said.

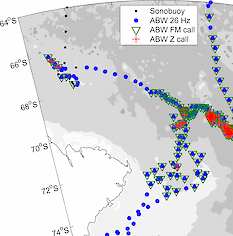

‘We were able to triangulate their position with the sonobuoys and when we got to the location a few days later we were staggered to witness many large groups of whales in a relatively small area of about 100 square kilometres.’

For the duration of the the voyage, on board New Zealand’s research vessel Tangaroa, the sonobuoys allowed the team to pick up more than 40,000 whale calls, some more than 1,000 km away, and make 520 hours of song recordings. The team was also able to photo-identify 58 individuals through the mottled patterns on their skin, and collect one skin biopsy for DNA analysis. The photos and biopsy will contribute to a global repository of circumpolar data, for longer-term analysis.

The work is part of the Australian Government’s ongoing commitment to the International Whaling Commission’s Southern Ocean Research Partnership. The partnership aims to develop, test and implement non-lethal scientific methods to estimate the abundance and distribution of whales and describe their role in the Antarctic ecosystem.

Like many whales, Antarctic blue whales were hunted to the brink of extinction during industrial whaling, and sightings have been extremely rare in the past 50 years. Between 1978 and 2010 blue whale surveys recorded only 216 visual encounters.

‘With such a patchy distribution it is only possible to study this endangered species efficiently using acoustic technology,’ Dr Double said.

Australian Antarctic Division acoustician, Dr Brian Miller, said the acoustic technology and methodology used by the team has developed sufficiently to allow them to gain insights into the behaviour of blue whales.

‘We can hear and track these animals over ranges much bigger than you can see them, so to try and study them without listening to them only gives you a part of the picture,’ Dr Miller said.

‘By looking and listening at the same time, we’re beginning to reconcile what we hear with what we see.’

For example, at the start of the voyage the team saw and heard two blue whales at the Balleny Islands. However, they also heard a few calls to the east of the islands and decided to follow their acoustic bearings. Within days their decision proved correct (Figure 1).

‘We started getting frequent, loud calls from the direction we were headed. And then we were inside the aggregation and the noise drowned out everything else,’ Dr Miller said.

‘We re-sighted the two whales we’d seen at the Balleny Islands, so they must have taken a similar path to us to join the aggregation.

‘These observations support the idea that blue whales communicate with each other over vast distances. It could be that they’re calling to assemble in groups for feeding or breeding.’

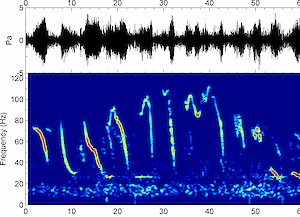

Dr Miller said the whales made two types of calls within the aggregation – frequency modulated (FM) calls and tonal ‘Z’ calls (Figure 2). The first component of the Z call, a 26 Hz tone, was heard at large distances from the aggregation.

‘We discovered a variety of forms of FM calls, which seem to be associated with animals in groups and may be shorter range, social or foraging sounds. The tonal calls seem to be produced more by individuals and could be for longer range communication.’

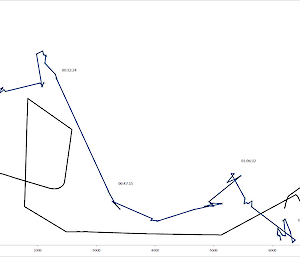

The team also recorded vocalisations while filming individual whales. Using a video coupled with a GPS and gyro compass, the team recorded dive times, surfacing locations and blows (Figure 3).

‘One of the whales we filmed would dive for about five minutes and then surface to blow a few times. It did this for about an hour and then its movements completely changed and it turned in circles and surfaced every minute, which is likely to be indicative of feeding,’ Dr Miller said.

‘By matching sounds with movements such as this, we may be able to identify sounds associated with feeding or breeding.’

While observers were enjoying the blue whales’ antics from the ship’s deck, a hardy group of data miners were analysing echosounding data in the bowels of the vessel for evidence of the whales’ food source – krill.

Echosounders send pings of sound into the water and then record the returning echo, which changes when it bounces off fish, krill and other reflective objects in the water column. The resulting images provide information about the location, distribution and density of the objects.

Australian Antarctic Division krill survey designer, Dr Martin Cox, said the krill aggregated in a distinctive way, quite different to anything he had encountered before.

‘Typically you’ll get dense patches of krill, but you’ll also get a sparse background level that sit in layers, 20 to 30 metres deep, which can stretch for tens to hundreds of kilometres,’ he said.

‘We didn’t see that at all. Instead we found huge balls of tightly packed krill and nothing else – no background. We estimated that one of the balls contained 100 tonnes of krill.’

The whale team hypothesise that blue whale aggregations could be driven by foraging and that these dense krill swarms suit the whales, allowing them to feed quickly and efficiently. However, more blue whale and krill surveys are need to confirm this.

‘We always found krill when we saw whales, so it could be that blue whales somehow know that krill form these dense aggregations in certain areas,’ Dr Cox said.

As well as the blue whale research, the team spent time tracking humpback whales near the Balleny Islands, again acquiring photo-identifications and 10 biopsy samples and collecting samples of water, krill and fish to understand food availability.

With the whale studies completed, the expedition moved to Terra Nova Bay in the Ross Sea to explore any ecosystem effects of commercial toothfish fishing.

National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) fisheries scientist, and Voyage Leader, Dr Richard O’Driscoll, said the team conducted 18 trawl surveys to examine the abundance and distribution of species that make up the bycatch of the toothfish longline fishery, including grenadiers and icefish.

‘We caught over 100 species or species groups from the trawls and collected 370 sample lots for taxonomic identification,’ Dr O’Driscoll said.

‘The data collected will help validate models and inform management decisions by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources.’

The team also deployed an echo sounder, moored in 550 m of water in Terra Nova Bay, to monitor the spawning of Antarctic silverfish; one of the main Antarctic prey species.

‘The instrument will detect and record the abundance of silverfish over winter to see whether there is a mass migration of the fish to the Ross Sea over winter, or whether their eggs drift in from somewhere else,’ Dr O’Driscoll said.

After their 15,000 km journey, the team is confident the data and samples collected will add significantly to scientists’ understanding of the Southern Ocean ecosystem.