As Australia commemorates the centenary of its involvement in World War I and the Battle of Gallipoli (25 April 1915 — 9 January 1916), it is timely to reflect on the contribution many Antarctic explorers made to the war effort.

Following a sense of adventure or patriotism, or simply the call of friendship, many people who had experience in Antarctic exploration volunteered to serve in the armies of World War I.

Traces of many of these men, the records they leave in maps, diaries, photographs, printed materials and ephemera are preserved in the State Library of New South Wales. They are a reminder of the contribution they made to our understanding of the world. In the worst case, they are a reminder of their sacrifice and of an untimely end to a life of potential and contribution.

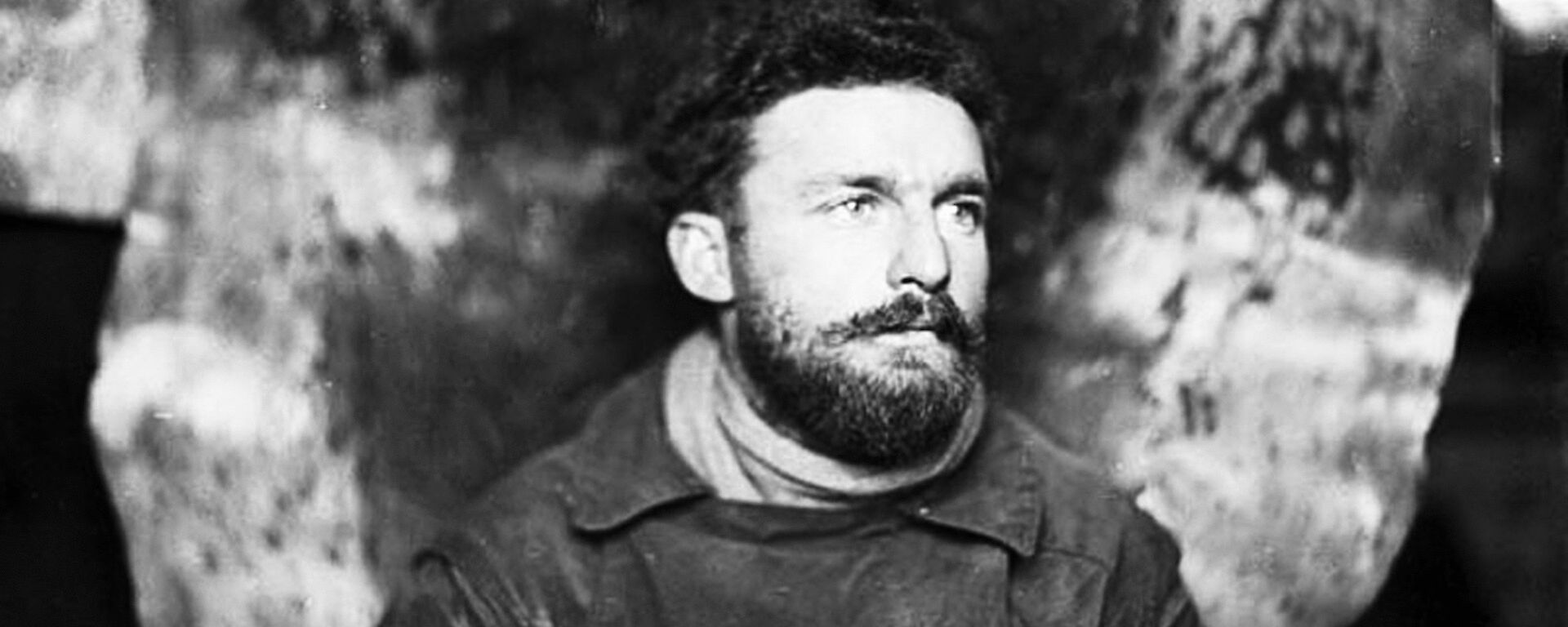

Companions in the south, the paths of these men sometimes crossed in the trenches of the European war. Here, Australian photographer Frank Hurley met sledging companions Leslie Russell Blake and Eric Webb. A few years before, during their expedition towards the South Magnetic Pole, these friends nearly died in the harsh and dangerous conditions on the Antarctic plateau. Later, while on leave in London, Hurley met both Douglas Mawson and Ernest Shackleton.

The living conditions on the front often reminded men like Hurley of his experiences in the south. Only a short time after his extraordinary time lost on the bitter Antarctic Elephant Island and living for 4 ½ months with 21 others under upturned lifeboats, Hurley wrote in his war diaries about the warmth of companionship. In his diary, he commented on his response to the carnage while walking through battlefields strewn with dismembered corpses:

The Menin road is like passing through the Valley of Death, for one never knows when a shell will lob in front of him. It is the most gruesome shambles I have ever seen, with the exception of the South Georgia whaling stations, but here it is terrible as the dead things are men and horses. [17 September 1917]

'On 30 December 1917, Hurley was with members of the Australian Light Horse in Palestine. That evening the men made camp, settling and feeding the horses. As the dark grew around them, the soldiers gathered around a fire and asked Hurley to tell them about Antarctica. In this extraordinary moment the connections between the experiences of the explorers of the then almost completely unknown southern continent and the experiences of people in World War 1 became apparent. He wrote about the episode:

After dinner the boys invited me to their campfire, and asked me to give them a few words about my Antarctic experiences. The novelty of the surroundings impressed me greatly, and I felt, in the interest expressed on the faces around me a reward for the tribulations of the South… How all these, my fellow countrymen appreciated my story. How they sympathized with the hardships and how they joined in hilarity when I related… the primitive routine of daily life. I enjoyed it as much as they.'

He completed his entry with a reflection that the companionship of these men reminded him of that of the Antarctic teams, sleeping in cramped and dangerous circumstances: ‘tightly packed, but warm and contented’

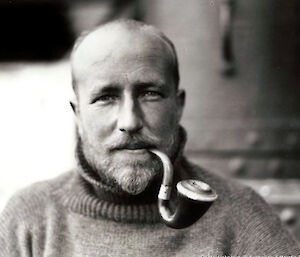

Sir Ernest Shackleton, famous for his expeditions to Ross Island and the Trans Antarctic Expedition, came to Sydney in 1917 and assisted the Australian recruitment drive by writing the pamphlet A Call to Australia:

Here in Australia the call to service sounds loud and clear. I speak to you men as one who has carried the King’s flag in the white warfare of the Antarctic and who is going now to serve in the red warfare of Europe. I say to you that his call means more than duty, more than sacrifice, more than glory. It is the supreme opportunity offered to every man of our race to justify himself before his own soul. Love of ease, love of money, love of woman, love of life — all these are small things in the scale against your own manhood. The blood that has been shed on the burning hills of Gallipoli and the sodden fields of Flanders calls to you. Politics, prejudices, petty personal interests are nothing. Fight because you have the hearts of men, and because if you fail you will know yourselves in your own inner consciousness to be for ever shamed. And to the women of Australia, I would say just this: be as the women of Rome, who said to husbands, brothers, and fathers, ‘Come back victorious, or on your shields’.

Some of these men died while in the war. Bob Bage, a fellow expeditioner of Webb and Hurley, was killed at Gallipoli. Twelve days after the landing, he was shot by Turkish machine gun fire as he laid out trench lines near Lone Pine. His scientific field books are preserved in the Mitchell Library. In these, his careful measurements of the progress towards the south magnetic pole are recorded in a tight, precise hand.

Leslie Russell Blake, another of the men of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, died on 3 October, 1918 just weeks before the Armistice. He was awarded the Military Cross. Blake’s beautiful and carefully drafted map of Macquarie Island is one of the most accurate representations of that remarkable island.

Others served in different ways. Morton Moyes, meteorologist with Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition, was a naval instructor during the War. Despite attempts to leave this post and go on active service in the Navy, he was considered too valuable as a trainer to go to war. In 1917, he sailed south with the Aurora on the relief expedition for the Ross Sea party with Shackleton as his cabin mate. The official log of this voyage and an oral history by Ross Bowden with Moyes are both in the Mitchell Library collection.

After the war Hurley wrote in the Australasian Photo-Review (14 February, 1919):

What a contrast to the ice fields of Antarctica! It would be impossible to find in the vast domain of photography two branches of work more divergent. In the latter — everything beautiful, reposeful, and of infinite charm; the former, filled with horror — it was all action and suffering.

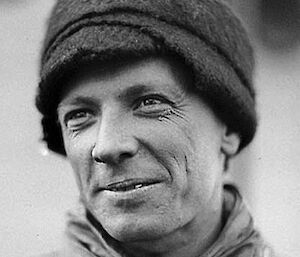

Like Hurley and members of the Light Horse around the campfire in the Judean Hills, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, assistant zoologist with Sir Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated British National Antarctic Expedition (1910–1912), valued the friendships forged in the south. Garrard attempted to serve in the war but, afflicted with nervous damage, returned to London. However his comments about friendship and reliance in Antarctica ring true for both fields of endeavour. In his book about his Antarctic experiences, The Worst Journey in the World, Cherry-Garrard wrote about the companionship of the men on a harsh sledging journey as ‘gold, pure unalloyed gold’.

Stephen Martin

Stephen is a former senior librarian and researcher for the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and has been visiting Antarctica as a history lecturer, field guide, sailor and tourist for the last two decades. He is the author of A History of Antarctica (Rosenberg Publishing, 1996; revised 2013).