As a keynote speaker at the ‘Strategic Science in Antarctica’ conference, Jason Mundy, General Manager of the Australian Antarctic Division’s Strategies Branch, shared his insights on the broad theme of the conference; the interface between science and policy. Jason is a former diplomat and Ministerial adviser, with a background in public policy, international relations, diplomacy and strategy. He provided conference delegates with a thought-provoking ‘end user’ perspective. Following is an edited excerpt of his presentation.

What are Australia’s — and the world’s — Antarctic policy priorities? And how, from a policy maker’s perspective, can science best work to inform and influence the governance, management and stewardship of Antarctica?

For the Australian Antarctic Division, particularly the Strategies Branch, resolving these questions is crucial to the shaping and delivery of genuinely ‘strategic science’. Antarctic policy includes the administration of the Australian Antarctic Territory, environmental management, and our involvement in the Antarctic Treaty System — mainly through the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). In both of those forums, science input — and close relationships between researchers and policy officers — is vital to achieving Australia’s outcomes.

The interplay between science and strategy in Antarctica is intimate and well-established. For Australia, it can be traced back to the early explorations by geologist Douglas Mawson. Unlike other explorers from the heroic age, who were focused on the South Pole, Mawson made a clear decision to devote his Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911–14) to conducting science and surveying the coastline of eastern Antarctica. He understood, and didn’t hesitate to tell his financial backers, that his explorations had broader strategic implications, writing in The Home of the Blizzard:

What will be the role of the South in the progress of civilization and in the development of the arts and sciences, is not now obvious. As sure as there is here a vast mass of land with potentialities, strictly limited at present, so surely will it be cemented some day within the universal plinth of things.

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was of tremendous strategic and historical significance for Australia. It was Australia’s first major scientific undertaking following Federation, and it was a key precursor to Australia’s eventual assertion of sovereignty over the Australian Antarctic Territory.

Despite a huge evolution in the world’s understanding of Antarctica, the continent continues today to attract attention in part because of those vast potentialities that Mawson observed a hundred years ago.

Australia’s policy priorities

Australia’s key policy priorities in Antarctica today are well defined, and captured in the Australian Antarctic Science Strategic Plan. They have been endorsed by a series of Australian Governments in something like their current form for about 20 years.

Australia’s top-tier objectives in Antarctica cut across six key themes. Science is one of these, but so too is physical presence in the Australian Antarctic Territory; influence in the Antarctic Treaty system; environmental management; collaborative relationships with other national programs; and pursuit of reasonable economic benefits (not including mining or oil drilling). It’s important to understand that these themes don’t exist in isolation from one another; they are cross cutting.

It’s important that the Antarctic science community keeps an eye to the broader strategic horizon when considering and framing proposals for science research in Antarctica. Research that aligns with, and achieves outcomes against, a number of these broader goals in Antarctica, will often look more attractive to a policy decision-maker than research that doesn’t.

Pathways to policy — some triumphs

Both Australia and New Zealand punch above their weight when it comes to exerting influence in the Antarctic Treaty system, due to the quality and targeted nature of the science produced specifically to support our effectiveness in international forums.

Australia benefits from having a structure in which Antarctic science, policy and operations are all integrated under one roof, in the Australian Antarctic Division. In an international context this configuration is relatively rare. Of course, a huge amount of critical and high quality Antarctic science is also contributed from universities and other scientific institutions outside the Antarctic Division. But there is no question that advantages derive to the national program from having an integrated structure, which encourages an intimate and flexible relationship between scientists, policy-makers and operators.

The following Australian examples, from CCAMLR and the ATCM’s Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP), highlight the importance of close relationships between science and policy, and the benefits of getting it right

Committee for Environmental Protection

The CEP’s main role is to provide advice and develop tools to assist Antarctic Treaty Parties to meet their goal of comprehensively protecting the Antarctic environment. It isn’t a scientific body, but it needs high quality scientific information to do its work well.

The types of questions that the CEP deals with include:

- What is the state of the Antarctic environment, or environments?

- What is changing — or is likely to change — and by how much?

- How should we respond to the changes?

- How do human activities in the Antarctic — national Antarctic programs, tourism and other non-government activities — interact with the environment?

- Can the interactions be managed, and if so how?

- How do external pressures, such as climate change, need to be considered in all this?

Scientific information is critical when considering each of these questions, and in making sure that the international community’s work is focused on addressing the most important issues. In many ways this resembles an environmental risk assessment approach. But it’s one that’s conducted through the lens of a multilateral forum that operates by consensus; so political science can also play a role. The CEP really is one of the closest interfaces between science and policy in the Antarctic world.

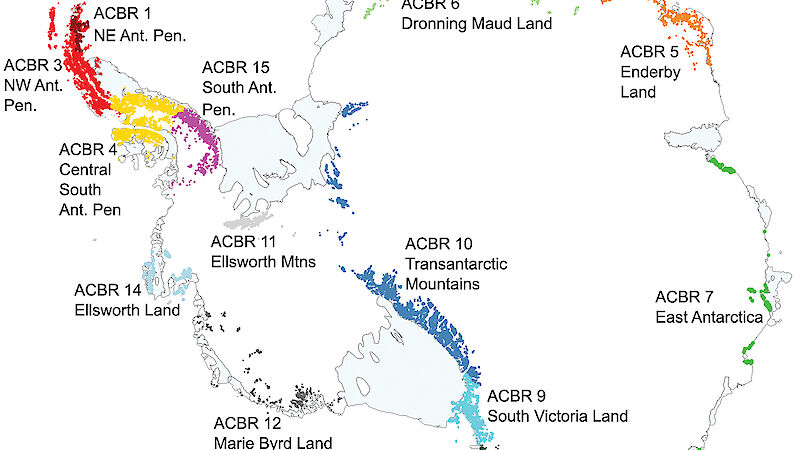

The recent identification of Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions is a great example of policy-relevant science feeding into the CEP. Dr Aleks Terauds and other contributors drew together all the available terrestrial biodiversity data, to identify 15 biologically distinct ice-free areas in Antarctica (Australian Antarctic Magazine 23: 19, 2012). This built on excellent work by New Zealand researchers to identify 21 discrete Environmental Domains based on physical parameters.

This scientific understanding of how biological diversity varies across Antarctica will be fundamental to shaping future environmental protection efforts there.

For example, the Environmental Protocol asks us to protect representative examples of major terrestrial ecosystems, so we need to know what these ecosystems are and where they are. Similarly, if we want to prevent species being transferred to areas where they are not naturally found, we need to understand the differences between one bioregion and another.

The bioregions have been endorsed by the CEP as a sound basis for informing its decision making and they’re going to be an influential tool for policy-makers in the years ahead.

Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources

CCAMLR is another example of an intimate and extremely productive relationship between science and policy. The very structure and foundation of the Commission is based on a linear relationship between scientific advice, provided by a Scientific Committee, which feeds directly into decisions in the policy-oriented Commission in the form of management measures.

Most recently we have seen this play out in the development and promotion of marine protected area proposals in the CCAMLR domain. Establishing marine protected areas in East Antarctica is Australia’s number one priority in CCAMLR at the moment (Australian Antarctic Magazine 24: 28, 2013).

A cornerstone of the development of these proposals has been rigorous consideration of the scientific basis and merit of the proposals by CCAMLR’s Scientific Committee. The success of a measure as ambitious as marine protected areas in East Antarctica is completely reliant on the twin streams of science and policy and our ability as representatives of Australia to draw them together effectively.

Through CCAMLR we also have the example of work to reduce bycatch of albatrosses and petrels — species which are iconic, long-lived and threatened by some types of fishing practices such as longlining.

This work has involved scientific research to identify and test mitigation techniques; industry cooperation and a willingness to work with scientists to implement mitigation technologies; and international cooperation among CCAMLR Parties to develop and refine binding conservation measures.

The results have been dramatic. Seabird mortalities from longline fishing in one key CCAMLR division fell from 6000 birds per year in 1996 to just 21 seabirds in 2000. That’s just one division of the CCAMLR fishery, but it’s a snapshot of a bigger success story, and an example of what can be achieved through a highly effective interface between science and policy.

International policy

Any discussion of science informing Antarctic policy wouldn’t be complete without reference to the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, or SCAR, which plays an important role in facilitating international cooperation on high quality science in the Antarctic region.

SCAR is older than the Antarctic Treaty system itself and it’s been a major and influential contributor to the ATCM since the Antarctic Treaty was signed in 1959. The scientific advice provided by SCAR regularly forms the basis for ATCM Parties’ discussions and decisions on a wide range of issues.

A current initiative is the first SCAR Antarctic and Southern Ocean Horizon Scan, which aims to draw together the best thinking on the top Antarctic scientific questions for the next two decades. This work will provide an excellent basis for the nations active in the Antarctic region to discuss how they can work together to tackle the big Antarctic science questions; consistent with the cooperation on scientific endeavour that is at the heart of the Antarctic Treaty.

Also noteworthy in the international Antarctic policy space is the recent adoption by the ATCM of a Multi-Year Strategic Work Plan. This initiative, promoted by Australia, was adopted at this year’s ATCM as an agreed list of collective priorities for the Antarctic treaty parties, and it’s a great guide and reference point for anyone who wants to know where the work of the Antarctic nations is headed in the future, including the science community.

Finally, it’s worth noting the role that scientific collaborations can play as fundamental tools of what’s known as ‘soft diplomacy’ — a concept very familiar to politicians, strategists, diplomats and foreign policy makers, including those who are not experts on the science itself.

Science collaborations are great for building links between people, and they’re often excellent ways to build some resilience and positive elements into otherwise thin or unsettled bilateral relationship. They are also tools of economic diplomacy which can help to promote Australia’s image as an innovative and technologically advanced country in ways that boost our overall attractiveness as an investment destination or trading partner.

One example of this being recognised at the strategic level in Australia is the Asian Century White Paper released by the Australian Government in October 2012. One of the identified pathways towards achieving closer integration between Australia and Asia over the coming decades is for the government to: ‘Support Australian researchers to broaden and strengthen their partnerships with the region as Asia grows as a global science and innovation hub’. Antarctic science is one of the most prospective avenues through which this pathway can be advanced, particularly given the close links between Australian researchers and counterparts in China, Japan, India and Korea, four of the five key Asian partners identified in the White Paper.

Finally, I’d like to reflect on the words of former UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband, speaking at the 2010 Inter-Academy Panel of the British Royal Society: ‘The scientific world is fast becoming interdisciplinary, but the biggest interdisciplinary leap needed is to connect the worlds of science and politics’. That’s a nexus we in Australia have been working hard to strengthen, and which will be bolstered further through the exchanges at this conference.