Two novel devices designed to prevent toothed whales from stealing valuable fish from pelagic longlines will shortly undergo their first ‘proof of concept’ test in Australian waters.

If successful, the devices could precipitate development of new technologies that will help reduce the death and injury of whales in pelagic (open ocean) longline fisheries, while improving the economic benefits to fishers.

The devices, dubbed the ‘Tuna Guard–Streamer Pod’ and the ‘Whale Shield–Jellyfish’, aim to deter toothed whales from removing or damaging fish caught on pelagic longlines — a practice known as ‘depradation’.

‘Both devices work on the principle that depredating whales are deterred by the presence of tangles in fishing gear,’ says Australian Antarctic Division marine biologist, Mr Derek Hamer.

‘We hope to use this apparent behaviour to our advantage to keep the whales away from the longline hooks and the catch, thus preventing by-catch and depredation events.’

The journey from problem to invention began 18 months ago when Mr Hamer, through the Australian Marine Mammal Centre, was tasked with developing a non-lethal method of preventing depredation (of primarily tuna and billfish) from pelagic longlines.

Pelagic longlines are typically comprised of a main line that runs horizontally in the water for up to 75km, which is suspended by a series of buoys at depths of between 30 and 300m. Dropping vertically from this main line at regular intervals are lengths of line called ‘snoods’, which each end in a baited hook. Each longline can accommodate up to 3600 baited hooks.

As the target fish can exceed AUS$2000 each in the high value sashimi markets in Japan, any losses through depredation by toothed whales can have big economic impacts. Some companies have reported revenue losses of between 7% and 30%, attributed to depredating whales. At least 15 species of toothed whales have been implicated in this global problem, including pilot, melon-headed, false killer and killer whales.

‘Reports of depredation by whales from pelagic longlines have increased over the last decade,’ Mr Hamer says.

‘This may be linked to improved reporting, but declines in whales’ natural prey stocks from overfishing may have forced some toothed whale populations to switch to alternative food sources that have become more reliable and abundant.

‘Also, toothed whales are intelligent animals and over time many individuals may learn that tuna caught on longlines are an easy source of food. It is also possible that this depredating behaviour could be passed down the generations.’

Mr Hamer began addressing the problem by talking to fishers and in late 2009 he spent almost three weeks on the Queensland-based longliner FV Fortuna. Here he observed the general fishing operation and interactions with toothed whales, gained insights into the perceptions of the crew towards depredation and sought their advice on possible ways to mitigate the behaviour.

He then broadened his ‘fact finding mission’ to Samoa and Fiji, where depredation of longlines by toothed whales also seems to be increasing.

‘This is a global problem, so it’s logical to have broader involvement. This ensures we can take into account the nuances of each fishery when developing these “physical depredation mitigation devices”,’ Mr Hamer says.

His insights helped set some ground rules for device development.

‘Given the large number of hooks typically deployed during longlining, even very small increases in the time required to set or haul each hook could see substantial increases in the duration of fishing activities, or decreases in the time the line is in the water, or the number of hooks set,’ Mr Hamer says.

‘So one of the criteria for an effective mitigation device is to ensure that impediments to setting and hauling time are minimal or negligible.’

Other fishers had also related to Mr Hamer that fish caught in or immediately adjacent to tangles in the fishing gear remained undamaged. In fact, depredation mitigation devices based on a similar principal have been trialled successfully in a ‘demersal’ (sea floor) longline fishery in South America, to deter sperm and killer whales. However, as pelagic fishing gear is in reach of diving toothed whales (unlike demersal gear which runs along the sea floor), pelagic depredation mitigation devices are necessarily more complicated than demersal ones. These observations now underpin Mr Hamer’s device development.

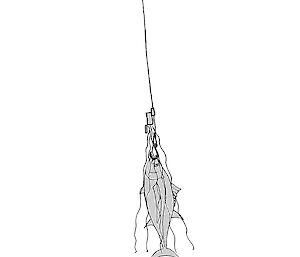

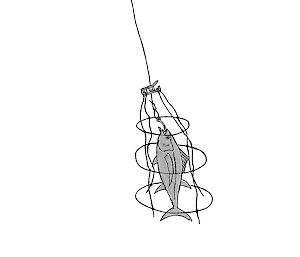

To imitate tangles in the fishing gear the Tuna Guard–Streamer Pod uses lengths of fine chain that dangle next to the caught fish, while the Whale Shield–Jellyfish uses a cage-like structure that completely envelops the caught fish. The devices remain clear of the baited hook until a fish is caught and then the pressure of the fish on the line causes the device to deploy and descend the snood towards the hook.

Mr Hamer will now spend up to a month at sea on the FV Fortuna comparing depredation rates on snoods fitted with each device and snoods without devices, under otherwise normal fishing conditions.

‘We’ll conduct a controlled experiment where each day we will set 500 unaltered hooks and 500 hooks with devices attached, and see if the devices actively deter whales,’ Mr Hamer says.

‘If we encounter major hurdles in the first trial then we may have to go back to the drawing board, but we’ll have a lot more knowledge to draw on. If the trials are successful we’ll look at modifying the devices to improve their operational capacity and reduce cost.’

Despite the potential advantages for whale conservation and depredation mitigation, the use of mitigation devices will come at a cost. Whether fishers take up the technology will depend on the running costs of their operation, the value of the target fish and the cost of the devices.

‘Currently no longline fisheries are required to implement depredation mitigation device technologies, so uptake will be voluntary. This can be better than relying on management and regulation, because many of the world’s fisheries lack the resources to ensure compliance,’ Mr Hamer says.

‘Each licence holder or fisher will have to do their own cost-benefit analysis to determine if the investment in these devices is economically worthwhile. We are hopeful there will be an economic incentive in it if fishers come home with a more valuable catch. As such, our short to medium term goal is to produce a device that works, then to make it cheap enough to purchase.’

Only time will tell if a win-win solution for whales and fishers can be untangled from the depredation problem.

WENDY PYPER

Corporate Communications, Australian Antarctic Division