Antarctica is often thought of as a pristine land untouched by human disturbance. Unfortunately this is no longer the case. For little more than a hundred years people have been travelling to Antarctica and in that short time most parts have been visited and we have left more than just footprints. We have driven some Antarctic species to the verge of extinction for economic benefit, killed and disturbed other species, contaminated the soils, discharged sewage to the sea and left rubbish, cairns and tracks in even the most remote parts. More recently attitudes have changed as we begin to realise that there are few unvisited places left on earth and that they of enormous value to humanity. The clean air, water and ice of Antarctica are now of global importance to science for understanding how the Earth’s environment is changing both naturally and as a result of human activity. Tourist operators are beginning to tap the huge demand to visit the last great wilderness on Earth. Paradoxically both science and tourism have the potential to damage the very qualities that draw them to Antarctica.

Scales of environmental impacts in Antarctica

Environmental impacts in Antarctica may occur at a range of spatial scales. At the largest scale are the effects in Antarctica of planet-wide impacts such as global warming, ozone depletion and global contamination caused by the application of technology elsewhere in the world. More localised, but still with the potential to cause region-wide effects, are the impacts of fishing and hunting. Mining has been prohibited under the Environmental Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty. More localised still are the impacts of visitors, such as scientists or tourists, to the region.

Global impacts

Antarctica is important for understanding the global impacts of the industrial world for a number of reasons. Global change may have deleterious effects that impact directly on the Antarctic environment and its fauna and flora. For example global warming may contribute to break-up of large areas of ice-shelf and cause loss of habitat for animals dependent on the ice-shelf; increasing UV radiation may cause changes to phytoplankton communities and could have effects up the food chain. Global change may also bring about changes in the Antarctic that could have serious environmental consequences elsewhere in the world, for example changes in the amount of water locked up in Antarctic ice may contribute to global sea level change. Finally, the Antarctic region is a sensitive indicator of global change. The polar ice cap holds within it a record of past atmospheres that go back tens or even hundreds of thousands of years, allowing study of the earth’s natural climate cycles against which the significance of recent changes can be judged.

Impacts of hunting and fishing

Hunting for whales and seals drew people to the Antarctic in the early years of the 19th century and within a very few years caused major crashes in wildlife populations. The Antarctic fur seal was at the verge of extinction at many locations by 1830 causing a decline in the sealing industry, although sealing continued at a smaller scale well into the last century. The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (CCAS) was initiated in response to concerns that the sealing industry could be re-opened after some exploratory research to investigate the viability of sealing in the 1960s. Although commercial sealing did not recommence, the CCAS does establish a regime for sealing and provides for permissible catch limits for crabeater, leopard and Weddell seals, and a zoning system with closed seasons and total protection for Ross seals, southern elephant seals and certain species of fur seal. However, under Australian law Australians would not be granted a permit for commercial sealing in the Antarctic Treaty area. The seal populations of Macquarie Island have been protected by the island’s status as a wildlife sanctuary since 1933. The seals of Australia’s sub antarctic islands were further protected in 1997 when both Macquarie and Heard and McDonald Islands were added to the World Heritage list. The exploited seal populations of the Southern Ocean have in recent years recovered very substantially and are no longer endangered.

Whaling in the Southern Ocean began in earnest in the early 1900s and grew very quickly so that by 1910 it provided 50% of the world’s catch. The history of whaling is a repeated sequence of targeting the most profitable species, depleting stocks and moving on to previously less favoured species. Declining catches motivated international attempts to regulate whaling and led to the establishment of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) which first met in 1949. For many years the IWC had little success as an organisation that was established to manage whales as a sustainable resource, however falls in profits did succeed in driving many companies out of the whaling business.

In the 1960s the IWC became more effective when blue and humpback whales were fully protected; protection was extended to fin and sei whales in the 1970s and in 1986 the IWC decided to suspend all commercial whaling. Since the moratorium was initiated, whaling has been limited to one or two countries that undertake ‘scientific whaling’ purportedly as the basis for research. There are some indications that whale populations are beginning to recover but such long-lived species with low reproductive rates are incapable of rebuilding their numbers in just a few years.

Fishing is the only large-scale commercial resource extraction currently undertaken in the Antarctic Treaty area now that sealing and whaling have effectively ceased. The major impacts of fisheries are:

- potential for over-fishing of target species

- effects on those species dependant on the target species as a food source

- mortality of non-target species caught by fishing equipment

- destruction of habitat.

Over-exploitation has been a characteristic of most major fisheries world-wide and unless the controls established for the Southern Ocean fisheries are enforced they will be no exception to this. CCAMLR and the Australian legislation that implements the convention are different from the other environmental instruments relevant to the Antarctic as their aim is regulation of sustainable exploitation rather than outright protection. CCAMLR was established in 1981 at a time when commercial interests in krill were growing rapidly; it began to be truly effective as a management regime in 1991 when the first catch limits were set. From the outset CCAMLR was based on the principle that management of fisheries should include not just the target species but also dependent and associated species and their ecological relationships. As a consequence, much research effort has been directed towards understanding the interactions between krill and their predators. After the convention was established the krill fishery did not continue to grow as it had previously, partly because of the withdrawal of the Soviet fleet after the breakdown of the Soviet Union, but also because the cost of fishing and the value of krill in the market place meant that it was economically marginal. This hesitation in the growth of the industry has allowed some breathing space for those managing the fishery, however the economics are changing and there is now demand for krill as a food source for aquaculture and bait. As a consequence the 1999 catch of 100,000 tonnes is likely to be soon doubled.

The fish of the Southern Ocean have been the subject of exploratory fishing since the start of the century but large-scale fishing did not develop until the late 1960s when the Soviet Union targeted marbled notothenid and icefish around South Georgia. The fishery has not recovered from the early peak (400,000 tonnes in 1969–70) and the subsequent rapid decline. The Patagonian toothfish has recently been targeted at a number of locations in the Subantarctic. The fishery has attracted unauthorised operators from several countries that are working outside the regulatory framework. Illegal, unregulated or unreported fishing is of concern because it has the potential to undermine attempts to manage the stock as a sustainable resource. In 1999 CCAMLR adopted a catch documentation scheme which will help prevent illegally caught fish entering the markets of CCAMLR nations. Illegal fishing is also a concern because it may involve the use of techniques that can cause the death of non-target species as by-catch. In particular, albatross are taken inadvertently by long-line fishing. CCAMLR has introduced a Conservation Measure to reduce the incidence of seabird mortality during long-lining. The Australian Fisheries Management Authority limits the fishery around Heard and Macquarie Islands to trawling to minimise the impacts on seabirds. The Australian Antarctic Division has recently established a new program, Antarctic Marine Living Resources, to provide the scientific basis for ecologically sustainable management of Southern Ocean fisheries.

Bio-prospecting, or the collection of animals, plants and microbiota to explore their potential as sources of new chemicals of commercial value (pharmaceuticals, pesticides or in food processing) has occurred on a small scale in Antarctica. Large-scale collections of wild populations are unlikely even if a useful chemical is discovered due to the economics of activities in Antarctica. The precedent set elsewhere in the world is that synthetic analogues of biologically active chemicals are used in preference to continued harvest of natural populations. Aquaculture and the techniques of tissue culture and genetic modification are also being explored as methods for satisfying the demand for useful natural products.

Impacts of visitors

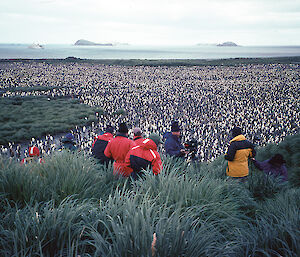

With the exception of those involved in fisheries, most visitors to the Antarctic go either as tourists or as part of national scientific programs. In many aspects the type of activities undertaken and the potential environmental impacts are common to all visitors. Irrespective of their reason for being in Antarctica, people will visit sites with spectacular scenery and in particular will visit wildlife colonies. However, there are some significant differences.

Although nearly three times as many people visited the Antarctic as tourists (14,000) as part of the national programs (4,000) in the 1999–2000 season, the number of person-days on the ground in Antarctica for national programs far exceeds the number for tourism. This is because to-date national programs have been characterised by the establishment of permanent or semi-permanent stations, mostly in the ice-free areas, staffed by long-term (wintering) and short-term (summer only) personnel. Most large-scale tourists operations are ship-based and landings are limited to a few hours at selected locations. There is a trend towards more independent, yacht-based visits and to adventure activities such as over-night camping, mountain climbing and scuba diving but this is unlikely to increase the number of person-days ashore to the point that tourism exceeds government activity in the foreseeable future.

The main concerns for environmental management are how to ameliorate past environmental impacts and how to reduce current and future impacts. Within the Australian Antarctic program we are developing procedures for the clean-up and remediation of abandoned work sites and disused tip sites. In the early days of Australia’s Antarctic program waste management consisted of disposal to open tips and the practice of sea-icing which involved pushing waste onto the sea-ice. Sea-iced material would travel out with the ice as it broke up at the beginning of summer to be dispersed among the marine environment. Commitment to the Madrid Protocol confers the obligation to clean-up abandoned work sites and waste tips so long as the process of clean-up does not cause greater adverse impacts or cause the removal of historic sites or monuments. Research is currently underway to develop cleanup and remediation procedures that will not cause greater impacts. Methods for detecting and monitoring impacts, particularly in the adjacent marine environment are also being developed.

Environmental audit, environmental impact assessment, a permitting system and a system of protected areas are among the arsenal of management tools available for reducing current and future impacts of activities in Antarctica. Environmental audit is used to assess our activities. A system of environmental impact assessment is included in the Madrid Protocol (and Australian legislation). The system, adopted by all nations operating in Antarctica, involves a preliminary assessment to determine the scale of impact likely and whether more detailed assessment is necessary. A permit system has also been established to regulate and monitor certain activities such as entry to protected areas and the collection of samples. The Madrid Protocol established a system for area protection and management, which will be used to protect areas of outstanding environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic or wilderness value. This system replaces the system of Specially Protected Areas and Sites of Special Scientific Interest previously designated by Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings.

Some environmental disturbance is an inevitable consequence of activities in Antarctica. These include emissions to the atmosphere such as exhaust; disturbance to the physical environment such as tracks from walking and vehicles; and disturbance to wildlife by visitors and vehicles. Environmental research and environmental management tools are used to reduce this disturbance. For example, research is being directed towards the potential for alternative energy sources to replace traditional fuels, the protected area system is used to ensure that vehicles are not used in particularly vulnerable landscapes and information from animal behavioural research is used as the basis for new guidelines to ensure that helicopters do not cause harm to aggregations of wildlife by flying too close.

Other, potentially more serious impacts, are not inevitable and may never happen but our presence in Antarctica means that there is a finite possibility that they will occur. Of particular concern is the risk of introducing species, including disease-causing species. Introduced species have caused major environmental problems on every other continent of the world and have caused significant changes to the ecology of most subantarctic islands. Although we can not remove the risk entirely, procedures are being developed on the basis of research findings to reduce the chance of introductions. Australia recently hosted the first international meeting to consider disease in Antarctic wildlife and has been asked to convene a group to develop practical measures to diminish the risk of introduction and spread of diseases to Antarctic wildlife.

Australian environmental initiatives

Protection of the Antarctic environment is one of the Government’s four goals for the Australian Antarctic program and the ethos of environmental protection suffuses all aspects of the program. The AAD, as lead agency for the Antarctic program, ensures that everyone involved in the program is aware of their personnel responsibility to care for the environment. At appointment, all expeditioners must agree to abide by the Code of Personal Behaviour, which includes a practical commitment to Australia’s environmental management responsibilities. Induction and training of new employees includes an introduction to the AAD’s approach to environmental matters. At the Antarctic stations, the station leader is responsible for environmental management and is assisted by the station environment committee, a station environmental officer and a station waste management officer.

At the headquarters of the AAD at Kingston, the Environmental Management and Audit Unit and the Operations Environment Officer are responsible for ensuring that all activities are planned carefully to avoid environmental harm and to develop policies that minimise detrimental effects on the natural environment.

The Human Impacts Research Program undertakes research to ensure that environmental management decisions are based on the best scientific information. The AAD’s Environment and Audit Committee brings together expertise from all sections of the organisation to provide senior management with support when making decisions that have implications to the environment. The Antarctic Marine Living Resources research program provides information that will be of use in managing the harvesting of species in the Southern Oceans.

Internationally, Australia has taken a leading role in promoting environmental protection within the Antarctic Treaty System since its inception. Australians were active in establishing the Agreed Measures in 1964 and the decision by Australia and France not to sign the Minerals Convention and to push for a protocol that accorded comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment led to the negotiating and signing of the Madrid Protocol. Australia is continuing its efforts within the Antarctic Treaty System to secure protection of the environment through contributions to the new Committee for Environmental Protection, which was established to provide environmental advice to the Treaty Consultative meetings. Scientists and policy advisors from the Antarctic Division participate in CCAMLR and information arising from Australian research has been the basis for Conservation Measures adopted by the Commission.

The environment of Antarctica is now the major issue of concern for the Antarctic Treaty System. Australia will continue to play a significant role in international Antarctic forums to argue for greater environmental protection for the region.

Martin Riddle

Human Impacts Research Program Leader,

Australian Antarctic Division