By GF Ainsworth

We had now thrown a year behind and the work we set out to accomplish was almost finished; so it was with pleasurable feelings that we took up the burden of completion, looking forward to the arrival of April 1913 which should bring us final relief and the prospects of civilisation. I shall deal with the first three months of the year as one period, since almost all the field work, except photography, had been done, and, after the return of Blake and Hamilton from Lusitania Bay on January 8, our life was one of routine; much time being devoted to packing and labelling specimens in anticipation of departure.

The first business of the year was to overhaul the wireless station, and on the 6th, Sawyer, Sandell and I spent the day laying in a supply of benzine from Aerial Cove, changing worn ropes, tightening stay wires, straightening the southern masts and finally hauling the aerial taut. These duties necessitated much use of the ‘handy billy’, and one has but to form an acquaintance with this desirable ‘person’ to thoroughly appreciate his value.

Blake and Hamilton returned on January 8 and reported that their work was finished at the southern end. Thenceforth they intended to devote their time to finishing what remained to be done at the northern end and in adding to their collections. Blake, for instance, resolved to finish his chart of the island, and, if time permitted, to make a topographical survey of the locality, as it was of great geological interest. Hamilton made the discovery that a number of bird specimens he had packed away were mildewed, and as a result he was compelled to overhaul the whole lot and attend to them. He found another colony of mutton birds on North Head, the existence of which was quite unexpected till he dug one out of a burrow thought to contain ‘night birds’.

About the middle of January I endeavoured to do a little meteorological work with the aid of some box kites manufactured by Sandell. But though a number of them were induced to fly, we had no success in getting them up with the instruments attached. They all had a habit of suddenly losing equilibrium and then indulging in a series of rapid dives and plunges which usually ended in total wreckage.

The Rachel Cohen again visited the island on January 26, but this time she anchored off ‘The Nuggets’, whither the sealers had gone to live during the penguin season. We could see the ship lying about a mile offshore, and walked down to get our mails and anything else she had brought along for us. I received a letter from the Secretary of the Expedition saying that he had made arrangements for us to return by the Rachel Cohen early in April, and the news caused a little excitement, being the only definite information we had had concerning relief.

The end of the first month found Blake and Hamilton both very busy in making suitable boxes for specimens. Many of the larger birds could not be packed in ordinary cases, so Hamilton had to make specially large ones to accommodate them, and Blake’s rock specimens being very heavy, extra strong boxes had to be made, always keeping in view the fact that each was to weigh not more than eighty pounds, so as to ensure convenient handling.

After a silence of about four months, we again heard Adélie Land on February 3, but the same old trouble existed, that is, they could not hear us. Sawyer called them again and again, getting no reply, but we reckoned that conditions would improve in a few weeks, as the hours of darkness increased.

Hamilton and I made a trip to the hill tops on the 4th for the purpose of taking a series of plant and earth temperatures which were of interest biologically, and while there I took the opportunity of obtaining temperatures in all the lakes we saw. Hamilton also took some panoramic photographs from the various eminences and all of them turned out well.

During the evening Adélie Land sent out a message saying that Dr Mawson had not yet returned to the Base from his sledging trip and Sawyer received it without difficulty, but though he ‘pounded away’ in return for a considerable time, he was not heard, as no reply or acknowledgment was made.

The Rachel Cohen remained till the 5th, when a northerly gale arose and drove her away. As she had a good cargo of oil on board no one expected her to return. We had sent our mail on board several days previously as experience had shown us that the sailing date of ships visiting the island was very uncertain.

Sandell met with a slight though painful accident on the 7th. He was starting the engine, when it backfired and the handle flying off with great force struck him on the face, inflicting a couple of nasty cuts, loosening several teeth, and lacerating the inside of his cheek. A black eye appeared in a day or two and his face swelled considerably, but nothing serious supervened. In a few days the swelling had subsided and any anxiety we felt was at an end.

We now had only two sheep left, and on the 8th Blake and I went to kill one. Mac accompanied us. Seeing the sheep running away, she immediately set off after them, notwithstanding our threats, yells and curses. They disappeared over a spur, but shortly afterwards Mac returned, and, being severely thrashed, immediately left for home. We looked for the sheep during the rest of the day but could find no trace of them, and though we searched for many days it was not till five weeks had elapsed that we discovered them on a small landing about halfway down the face of the cliff. They had apparently rushed over the edge and, rolling down, had finally come to a stop on the ledge where they were found later, alive and well.

On the 8th Adélie Land was heard by us calling the Aurora to return at once and pick up the rest of the party, stating also that Lieutenant Ninnis and Dr Mertz were dead. All of us were shocked at the grievous intelligence and every effort was made by Sawyer to call up Adélie Land, but without success.

On the following day we received news from Australia of the disaster to Captain Scott’s party.

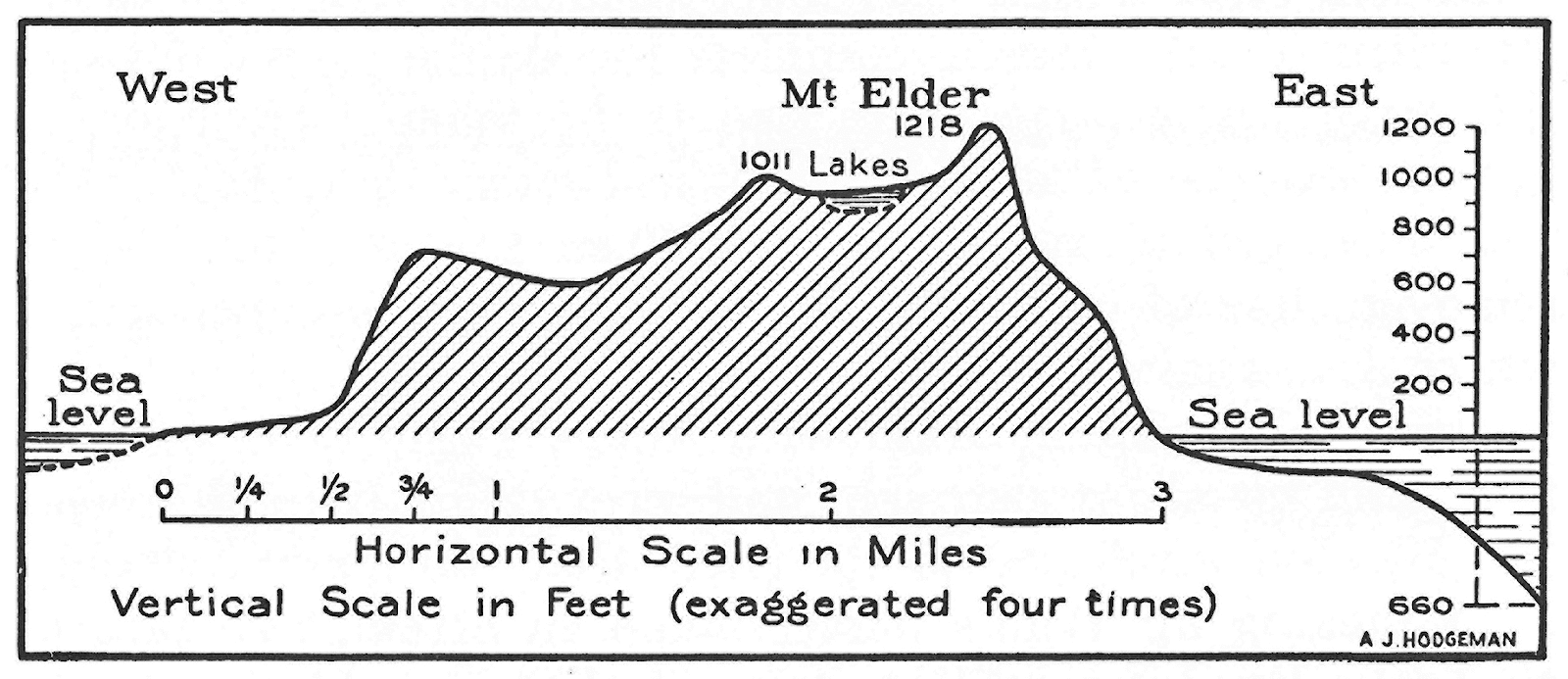

Blake, who was now geologising and doing topographical work, discovered several lignite seams in the hills on the east coast; he had finished his chart of the island. The mainland is simply a range of mountains which have been at some remote period partly submerged. The land meets the sea in steep cliffs and bold headlands, whose general height is from five hundred to seven hundred feet, with many peaks ranging from nine hundred and fifty to one thousand four hundred and twenty feet, the latter being the height of Mount Hamilton, which rears up just at the back of Lusitania Bay. Evidence of extreme glaciation is everywhere apparent, and numerous tarns and lakes are scattered amongst the hills, the tops of which are barren, windswept and weather worn. The hill sides are deeply scored by ravines, down which tumble small streams, forming cascades at intervals on their hurried journey towards the ocean. Some of these streams do not reach the sea immediately, but disappear in the loose shingly beaches of peaty swamps. The west coast is particularly rugged, and throughout its length is strewn wreckage of various kinds, some of which is now one hundred yards from the water’s edge. Very few stretches of what may be called ‘beach’ occur on the island; the foreshores consisting for the most part of huge water worn boulders or loose gravel and shingle, across which progress is slow and difficult.

Apparently the ground shelves very rapidly under the water, as a sounding of over two thousand fathoms was obtained by the Aurora at a distance of eight miles from the east coast. The trend of the island is about eleven degrees from true north; the axis lying north by east to south by west. At either end are the island groups already referred to, and their connection with the mainland may be traced by the sunken rocks indicated by the breaking seas on the line of reef.

A very severe storm about the middle of the month worked up a tremendous sea, which was responsible for piling hundreds of tons of kelp on the shore, and for several days tangled masses could be seen drifting about like small floating islands.

On the 20th an event occurred to which we had long looked forward, and which was now eagerly welcomed. Communication was established with the Main Base in Adélie Land by wireless! A message was received from Dr Mawson confirming the deaths of Ninnis and Mertz, and stating that the Aurora had not picked up the whole party. Sawyer had a short talk with Jeffryes, the Adélie Land operator, and among other scraps of news told him we were all well.

Hamilton killed a sea elephant on the 22nd. The animal was a little over seventeen feet long and thirteen and a half feet in girth just at the back of the flippers, while the total weight was more than four tons. It took Hamilton about a day to complete the skinning, and, during the process, the huge brute had to be twice turned over, but such is the value of the nautical handy billy that two men managed it rather easily. When the skin had been removed, five of us dragged it to the sealers’ blubber shed, where it was salted, spread out, and left to cure.

We had communication with Adélie Land again on the 26th, and messages were sent and received by both stations. Dr Mawson wirelessed to the effect that the Aurora would, after picking up Wild’s party, make an attempt to return to Adélie Land if conditions were at all favourable.

Finding that provisions were running rather short on the last day of February, we reduced ourselves to an allowance of one pound of sugar per week each, which was weighed out every Thursday. Altogether there were only forty–five pounds remaining. Thenceforth it was the custom for each to bring his sugar tin to the table every meal. The arrangement had its drawbacks, inasmuch as no sugar was available for cooking unless a levy were made. Thus puddings became rareties, because most of us preferred to use the sugar in tea or coffee.

March came blustering in, accompanied by a sixty–four mile gale which did damage to the extent of blowing down our annexe, tearing the tarpaulin off the stores at the back and ripping the spouting off the Shack. A high sea arose and the conformation of the beach on the northwestern side of the isthmus was completely changed. Numbers of sea elephants’ tusks and bones were revealed, which had remained buried in the shingle probably for many years, and heaps of kelp were piled up where before there had been clean, stony beach. Kelp is a very tough weed, but after being washed up and exposed to the air for a few days, begins to decay, giving forth a most disagreeable smell.

At this time we caught numerous small fish amongst the rocks at the water’s edge with a hand line about four feet long. It was simply a matter of dropping in the line, watching the victim trifle with destiny and hauling him in at the precise moment.

Wireless business was now being done nightly with Adélie Land, and on the 7th I received a message from Dr Mawson saying that the party would in all probability be down there for another season, and stating the necessity for keeping Macquarie Island station going till the end of the year. This message I read out to the men, and gave them a week in which to view the matter. The alternatives were to return in April or to remain till the end of the year.

I went through the whole of the stores on the 10th, and found that the only commodities upon which we would have to draw sparingly were milk, sugar, kerosene, meats and coal. The flour would last till May, but the butter allowance would have to be reduced to three pounds per week.

It was on the 12th that we found the lost sheep, but as we had some wekas, sufficient to last us for several days, I did not kill one till the 15th. On that day four of us went down towards the ledge where they were standing, and shot one, which immediately toppled off and rolled down some distance into the tussock, the other one leaping after it without hesitation. While Blake and Hamilton skinned the dead sheep, Sandell and I caught the other and tethered it at the bottom of the hill amongst a patch of Maori cabbage, as we thought it would probably get lost if left to roam loose. However, on going to the spot next day, the sheep was nearly dead, having got tangled up in the rope. So we let it go free, only to lose the animal a day or two later, for it fell into a bog and perished.

On March 22 a lunar eclipse occurred, contact lasting a little over three hours from 9.45 pm till within a few minutes of 1 am on the 23rd. The period of total eclipse was quite a lengthy one, and during the time it lasted the darkness was intense. Cloud interfered for a while with our observations in the total stage. No coronal effect was noted, though a pulsating nebulous area appeared in front of the moon just before contact.

A message came on the 27th saying that the Rachel Cohen was sailing for Macquarie Island on May 2, and would bring supplies as well as take back the men who wished to be relieved, and this was forwarded in turn to Dr Mawson.

He replied, saying that the Aurora would pick us up about the middle of November and convey us to Antarctica, thence returning to Australia; but if any member wished to return by the Rachel Cohen he could do so, though notification would have to be given, in order to allow of substitutes being appointed. All the members of the party elected to stay, and I asked each man to give an outline of the work he intended to pursue during the extended period.

During March strong winds were recorded on fourteen days, reaching gale force on six occasions. The gale at the beginning of the month was the strongest we had experienced, the velocity at 5.40 am on the 1st reaching sixty–four miles per hour. Precipitation occurred on twenty–six days and the average amount of cloud was 85 per cent. A bright auroral display took place on the 6th, lasting from 11.20 till 11.45 pm It assumed the usual arch form stretching from the southeast to southwest, and streamers and shafts of light could be observed pulsating upwards towards the zenith.

We now started on what might be called the second stage of our existence on the island. In the preceding pages I have endeavoured to give some idea of what happened during what was to have been our full period; but unforeseen circumstances compelled us to extend our stay for eight months more, until the Aurora came to relieve us in November. As the routine was similar in a good many respects to that which we had just gone through, I shall now refer to only the more salient features of our life.

The loyalty of my fellows was undoubted, and though any of them could have returned if he had felt so inclined, I am proud to say that they all decided to see it through. When one has looked forward hopefully to better social conditions, more comfortable surroundings and reunion with friends, it gives him a slight shock to find that the door has been slammed, so to speak, for another twelve months. Nevertheless, we all found that a strain of philosophy smoothed out the rough realities, and in a short time were facing the situation with composure, if not actual contentment.

We decided now to effect a few improvements round about our abode, and all set to work carrying gravel from the beach to put down in front of the Shack, installing a sink system to carry any waste water, fixing the leaking roof and finally closing up the space between the lining and the wall to keep out the rats.

We expected the Rachel Cohen to leave Hobart with our stores on May 2, and reckoned that the voyage would occupy two weeks. Thus, it would be six weeks before she arrived. I was therefore compelled on the 10th to reduce the sugar allowance to half a pound per week. We were now taking it in turns to go once a week and get some wekas, and it was always possible to secure about a dozen, which provided sufficient meat for three dinners. Breakfast consisted generally of fish, which we caught, or sea elephant in some form, whilst we had tinned fish for lunch.

Sandell installed a telephone service between the Shack and the wireless station about the middle of April, the parts all being made by himself; and it was certainly an ingenious and valuable contrivance. I, in particular, learned to appreciate the convenience of it as time went on. The buzzer was fixed on the wall close to the head of my bunk and I could be called any time during the night from the wireless station, thus rendering it possible to reply to communications without loss of time. Further, during the winter nights, when auroral observations had to be made, I could retire if nothing showed during the early part of the night, leaving it to Sandell, who worked till 2 or 3 am to call me if any manifestation occurred.

We had heavy gales from the 12th to the 17th inclusive, the force of the wind during the period frequently exceeding fifty miles per hour, and, on the first–mentioned date, the barometer fell to 27.8 inches. The usual terrific seas accompanied the outburst.

Finding that there were only eight blocks of coal left, I reduced the weekly allowance to one. We had a good supply of tapioca, but neither rice nor sago, and as the sealers had some of the latter two, but none of the former, we made an exchange to the extent of twelve pounds of tapioca for eight pounds of rice and some sago. Only fifteen pounds of butter remained on the 20th, and I divided this equally, as it was now one of the luxuries, and each man could use his own discretion in eating it. As it was nearing the end of April, and no further word concerning the movements of the Rachel Cohen had been received, I wirelessed asking to be immediately advised of the exact date of the vessel’s departure. A reply came that the ship would definitely reach us within two months. I answered, saying we could wait two months, but certainly no longer.

With a view to varying the menu a little, Blake and I took Mac up on the hills on April 26 to get some rabbits and, after tramping for about six hours, we returned with seven. In our wanderings we visited the penguin rookeries at ‘The Nuggets’, and one solitary bird sat in the centre of the vast area which had so lately been a scene of much noise and contention.

On May 1 I took an inventory of the stores and found that they would last for two months if economically used. Of course, I placed confidence in the statement that the Rachel Cohen would reach the island within that time.

With the coming of May wintry conditions set in, and at the end of the first week the migrants had deserted our uninviting island. Life with us went on much the same as usual, but the weather was rather more severe than that during the previous year, and we were confined to the Shack a good deal.

The sealers who were still on the island had shifted back to the Hut at the north end so that they were very close to us and frequently came over with their dog in the evenings to have a yarn. The majority of them were men who had ‘knocked about’ the world and had known many rough, adventurous years. One of them in particular was rather fluent, and we were often entertained from his endless repertoire of stories.

On the 23rd, finding that there were seventy–seven and a half pounds of flour remaining, and ascertaining that the sealers could let us have twenty–five pounds, if we ran short, I increased the allowance for bread to twelve and a half pounds per week, and this, when made up, gave each man two and three–quarter pounds of bread. Our supply of oatmeal was very low, but in order to make it last we now started using a mixture of oatmeal and sago for breakfast; of course, without any milk or sugar.

Just about this time Mac gave birth to six pups and could not help us in obtaining food. She had done valuable service in this connection, and the loss in the foraging strength of the party was severely felt for several weeks. She was particularly deadly in hunting rabbits and wekas, and though the first–named were very scarce within a few miles of the Shack, she always managed to unearth one or two somewhere. Hut slippers were made out of the rabbit skins and they were found to be a great boon, one being able to sit down for a while without his feet ‘going’.

June arrived and with it much rough, cold weather. A boat was expected to come to our relief, at the very latest, by the 30th. We had a very chilly period during the middle of the month, and it was only by hand feeding the ‘jacket’ of the wireless motor that any work could be done by the station, as the tank outside was almost frozen solid.

The tide gauge clock broke down towards the end of the month, and though I tried for days to get it going I was not successful. One of the springs had rusted very badly as a result of the frequent ‘duckings’ the clock had experienced, and had become practically useless.

We had ascertained that the Rachel Cohen was still in Hobart, so on the 23rd I wirelessed asking when the boat was to sail. The reply came that the Rachel Cohen was leaving Hobart on Thursday, June 26.

Our supply of kerosene oil was exhausted by the end of the month, despite the fact that the rule of ‘lights out at 10 pm’ had been observed for some time. Thus we were obliged to use sea elephant oil in slush lamps. At first we simply filled a tin with the oil and passed a rag through a cork floating on the top, but a little ingenuity soon resulted in the production of a lamp with three burners and a handle. This was made by Sandell out of an old teapot and one, two or three burners could be lit as occasion demanded. During meal times the whole three burners were used, but, as the oil smoked and smelt somewhat, we generally blew out two as soon as the meal was finished. This was the ‘general’ lamp, but each man had, as well, one of his own invention. Mine was scornfully referred to as the ‘houseboat’, since it consisted of a jam tin, which held the oil, standing in a herring tin which caught the overflow.

At the end of June, Blake and I surveyed all the penguin rookeries round about ‘The Nuggets’ and, allowing a bird to the square foot, found that there must have been about half a million birds in the area. The sealers kill birds from these rookeries to the number of about one hundred and thirty thousand yearly, so that it would seem reasonable to suppose that, despite this fact, there must be an annual increase of about one hundred thousand birds.

The end of the month arrived and, on making inquiries, we found that there was no news of the Rachel Cohen having left Hobart. We had enough flour to last a fortnight, and could not get any from the sealers as they possessed only three weeks’ supply themselves. However, on July 8, Bauer came across and offered to let us have some wheatmeal biscuits as they had a couple of hundredweights, so I readily accepted twenty pounds of them. We now had soup twice a day, and managed to make it fairly thick by adding sago and a few lentils. Cornflour and hot water flavoured with cocoa made a makeshift blancmange, and this, with sago and tapioca, constituted our efforts towards dessert.

On the 12th I received a message stating that the Rachel Cohen had sailed on July 7; news which was joyfully received. We expected her to appear in ten or twelve days.

On the 18th we used the last ounce of flour in a small batch of bread, having fully expected the ship to arrive before we had finished it. Next day Bauer lent us ten pounds of oatmeal and showed us how to make oatmeal cakes. We tried some and they were a complete success, though they consisted largely of tapioca, and, according to the respective amounts used, should rather have been called tapioca cakes.

When the 22nd arrived and no ship showed up, I went across to see what the sealers thought of the matter, and found that they all were of opinion that she had been blown away to the eastward of the island, and might take a considerable time to ‘make’ back.

On this date we came to the end of our meats, which I had been dealing out in a very sparing manner, just to provide a change from sea elephant and weka. We had now to subsist upon what we managed to catch. There were still thirty–five tins of soup, of which only two tins a day were used, so that there was sufficient for a few weeks. But we found ourselves running short of some commodity each day, and after the 23rd reckoned to be without bread and biscuit.

At this juncture many heavy blows were experienced, and on the 24th a fifty–mile gale accompanied by a tremendous sea beat down on us, giving the Rachel Cohen a very poor chance of ‘making’ the island. Our last tin of fruit was eaten; twelve tins having lasted us since March 31, and I also shared the remaining ten biscuits amongst the men on the 24th. We were short of bread, flour, biscuits, meats, fish, jam, sugar and milk, but had twenty tins of French beans, thirty tins of cornflour, some tapioca, and thirty tins of soup, as well as tea, coffee and cocoa in abundance. We had not been able to catch any fish for some days as the weather had been too rough, and, further, they appeared to leave the coasts during the very cold weather.

Sea elephants were very scarce, and we invariably had to walk some distance in order to get one; each man taking it in turn to go out with a companion and carry home enough meat for our requirements. We were now eating sea elephant meat three times a day (all the penguins having migrated) and our appetites were very keen. The routine work was carried on, though a great deal of time was occupied in getting food.

Bauer very generously offered to share his biscuits with us, but we fellows, while appreciating the spirit which prompted the offer, unanimously declined to accept them. We now concluded that something had happened to the ship, as at the end of July she had been twenty–four days out.

On August 3 we had a sixty–three mile gale and between 1 and 2 am the velocity of the wind frequently exceeded fifty miles per hour. Needless to say there was a mountainous sea running, and the Rachel Cohen, if she had been anywhere in the vicinity, would have had a perilous time.

A message came to me on August 6 from the Secretary of the Expedition, saying that the Rachel Cohen had returned to New Zealand badly damaged, and that he was endeavouring to send us relief as soon as possible. I replied, telling him that our food supply was done, but that otherwise we were all right and no uneasiness need be felt, though we wished to be relieved as soon as possible.

Splendid news came along on the 9th to the effect that the New Zealand Government’s steamer Tutanekai would tranship our stores from the Rachel Cohen on the 15th and sail direct for the island.

Sawyer now became ill and desired me to make arrangements for his return. I accordingly wired to the Secretary, who replied asking if we could manage without an operator. After consulting Sandell, I answered that Sandell and I together could manage to run the wireless station.

Everybody now looked forward eagerly to the arrival of the Tutanekai, but things went on as before. We found ourselves with nothing but sea elephant meat and sago, with a pound tin of French beans once a week and two ounces of oatmeal every morning.

We heard that the Tutanekai did not leave as expected on the 15th, but sailed on the afternoon of the 17th, and was coming straight to Macquarie Island. She was equipped with a wireless telegraphy outfit, which enabled us on the 18th to get in touch with her; the operator on board stating that they would reach us early on the morning of the 20th.

On the evening of the 19th we gave Sawyer a send–off dinner; surely the poorest thing of its kind, as far as eatables were concerned, that has ever been tendered to any one. The fare consisted of sea elephant’s tongue ‘straight’, after which a bottle of claret was cracked and we drank heartily to his future prosperity.

At 7.30 am on the 20th the Tutanekai was observed coming up the east coast, and as we had ‘elephanted’ at 6 am we were ready to face the day. I went across to the sealers’ hut and accompanied Bauer in the launch to the ship, which lay at anchor about a mile from the shore. We scrambled on board, where I met Captain Bollons. He received me most courteously, and, after discussing several matters, suggested landing the stores straight away. I got into the launch to return to the shore, but the wind had freshened and was soon blowing a fresh gale. Still, Bauer thought we should have no difficulty and we pushed off from the ship. The engine of the launch failed after we had gone a few yards, the boat was blown rapidly down the coast, and we were eventually thrown out into the surf at ‘The Nuggets’. The Captain, who witnessed our plight, sent his launch in pursuit of us, but its engines also failed. It now became necessary for the crew of the whale boat to go to the assistance of the launch. However, they could do nothing against the wind, and, in the end, the ship herself got up anchor, gave the two boats a line and towed them back to the former anchorage. The work of unloading now commenced, though a fairly heavy surf was running. But the whaleboat of the Tutanekai was so dexterously handled by the boatswain that most of our stores were landed during the day.

Sawyer went on board the Tutanekai in the afternoon, thus severing his connection with the Expedition, after having been with us on the island since December 1911. On the following morning, some sheep, coal and flour were landed, and, with a whistled goodbye, the Tutanekai started north on her visit to other islands.

Our short period of stress was over and we all felt glad. From that time onwards we ate no more elephant meat ‘straight’. A sheep was killed just as the Tutanekai left, and we had roast mutton, scones, butter, jam, fruit and rice for tea. It was a rare treat.

All the stores were now brought up from the landing place, and as I had put up several extra shelves some weeks previously, plenty of room was found for all the perishable commodities inside the Shack.

The beginning of September found me fairly busy. In addition to the meteorological work, the results of which were always kept reduced and entered up, I had to work on Wireless Hill during the evening and make auroral observations on any night during which there was a display, attending to the stores and taking the week of cooking as it came along.

Blake and Hamilton went down the island for several days on September 3, since they had some special observations to make in the vicinity of Sandy Bay.

The sea elephant season was now in progress, and many rookeries were well formed by the middle of the month. The skuas had returned, and on the 19th the advance guard of the royal penguins arrived. The gentoos had established themselves in their old ‘claims’, and since the 12th we had been using their eggs for cooking.

Early in September time signals were received from Melbourne, and these were transmitted through to Adélie Land. This practice was kept up throughout the month and in many cases the signals were acknowledged.

Blake and Hamilton returned to the Shack on the 24th, but left again on the 30th, as they had some more photographic work to do in the vicinity of Green Valley and Sandy Bay.

Blake made a special trip to Sandy Bay on October 30 to bring back some geological specimens and other things he had left there, but on reaching the spot found that the old hut had been burned to the ground, apparently only a few hours before, since it was still smouldering. Many articles were destroyed, among which were two sleeping bags, a sextant, gun, blankets, photographic plates, bird specimens and articles of clothing. It was presumed that rats had originated the fire from wax matches which had been left lying on a small shelf.

On November 9 we heard that the Aurora would leave Hobart on the 19th for Antarctica, picking us up on the way and landing three men on the island to continue the wireless and meteorological work.

We sighted the Rachel Cohen bearing down on the island on November 18, and at 5.15 pm she came to an anchorage in Northeast Bay. She brought down the remainder of our coal and some salt for Hamilton for the preservation of specimens.

On the next night it was learned that the Aurora had left Hobart on her way south, expecting to reach us about the 28th, as some sounding and dredging were being done en route.

Everybody now became very busy making preparations for departure. Time passed very quickly, and November 28 dawned fine and bright. The Rachel Cohen, which had been lying in the bay loading oil, had her full complement on board by 10 am, and shortly afterwards we trooped across to say goodbye to Bauer and the other sealers, who were all returning to Hobart. It was something of a coincidence that they took their departure on the very day our ship was to arrive. Their many acts of kindness towards us will ever be recalled by the members of the party, and we look upon our harmonious neighbourly association together with feelings of great pleasure.

A keen lookout was then kept for signs of our own ship, but it was not until 8 pm that Blake, who was up on the hill side, called out, ‘Here she comes’, and we climbed up to take in the goodly sight. Just visible, away in the northwest, there was a line of thin smoke, and in about half an hour the Aurora dropped anchor in Hasselborough Bay.